Six precious substances worth more than their weight in gold

And how their value changed over time.

The saffron war of 1374 lasted 14 weeks driven by a notion that the spice could cure plague. It can’t. But people lost their heads over it. It’s not just gold, diamonds, and oil we cherish and plunder. Seemingly benign commodities—whether it’s medicinal tea or stinky fungus—have exerted power over us for centuries. Here’s just a taste of their recent history.

White Truffle

Italy’s Tanaro river basin produces prized white truffles. In 2016, excess rains yielded bumper crops and sank wholesale prices 30 percent. New cultivation tactics involving careful irrigation and seed selection from known truffle-producing trees could further devalue the fungus. That is, if they can survive blight.

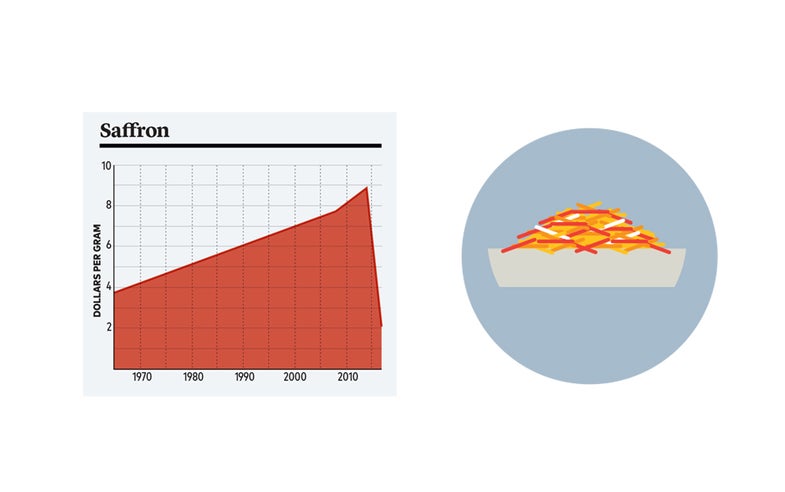

Saffron

The choice between Spanish and Iranian saffron is a matter of opinion. The complexly flavored pistils both come from the laborious harvest of the same tiny purple flowers. Some chefs prefer the Persian variety, but since the La Mancha spice can fetch twice the price, merchants relabel it, which forced the EU to crack down in 2014.

Beluga Caviar

The more we clamor for wild beluga caviar from the Caspian Sea, the more local fishermen will kill sturgeon for their eggs, and the scarcer the fish become—driving up prices. In 1998, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species tried to halt this cycle by limiting kill quotas, to fairly limited success.

Rhino Horn

The market for rhino horn, prized in Asia for its mythical medicinal value, peaked around 2012. But widespread education about rhino horn’s actual lack of medicinal value seems to be lowering prices. PSAs showing celebs like Richard Branson biting their finger-nails—made of keratin, like horns—probably helped.

Creme de la Mer

Astrophysicist Max Huber created the Crème in the ’60s to heal his rocket burns. Its luxury status intensified in 2005, when Estée Lauder launched a limited-edition version at invitation-only soirées. Champagne and fresh berries, plus the exclusivity, convinced socialites to pay $2,100 for a three-week supply.

Da Hong Pao Tea

Da Hong Pao Tea

This tea is said to have healed a 14th-century Ming emperor’s ailing mother. In gratitude, he placed a red robe around the trees, inspiring both the tea’s name (“big red robe”) and its cult status. The still-high price dropped in the 1980s after cultivators found a way to grow new trees from the Wuyi Mountain originals.

This article was originally published in the January/February 2018 Power issue of Popular Science.