The controversial tech driving James Dean’s return to the big screen

The studio bringing James Dean back for a new film suspects you’ll see a lot more digital actors going forward.

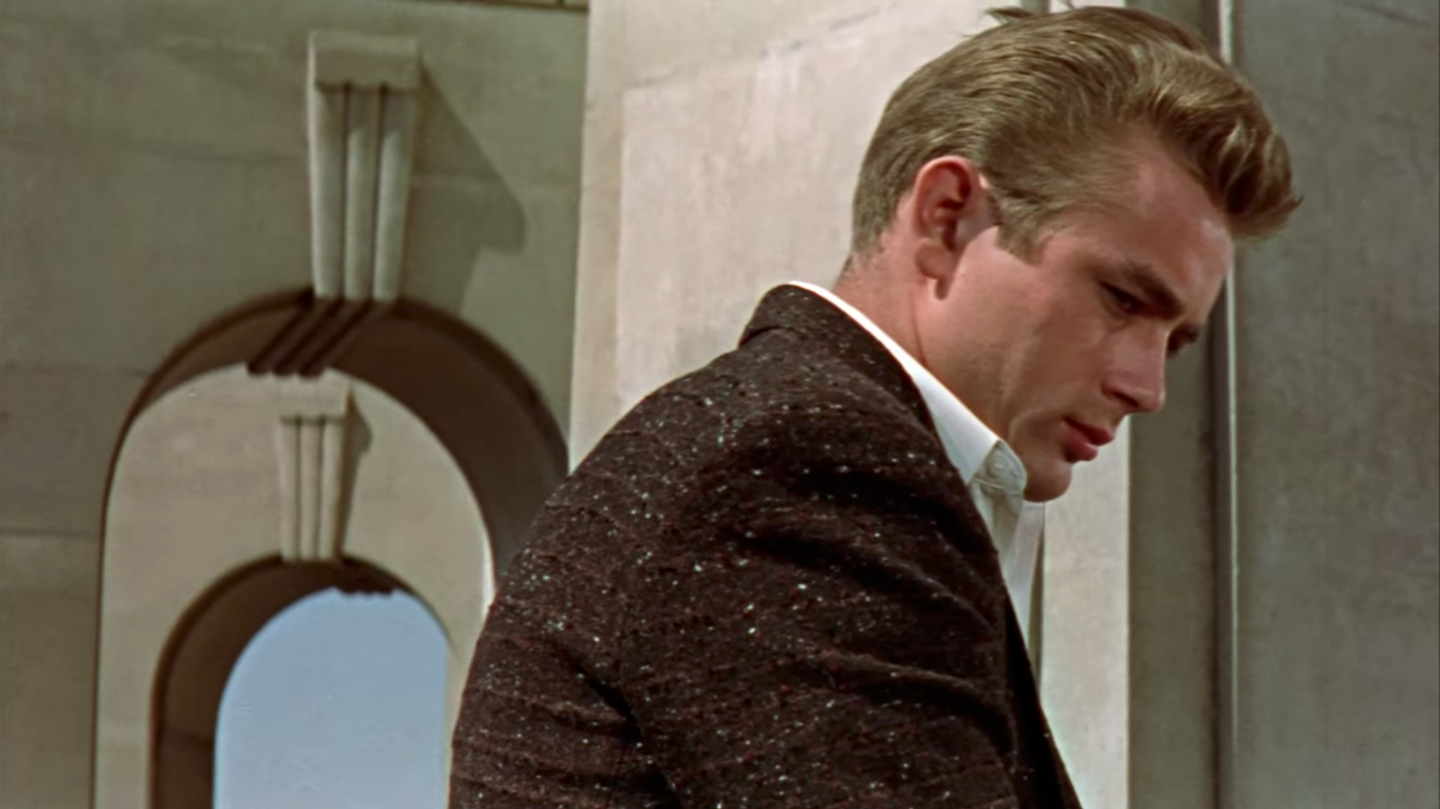

The tagline for Superman: The Movie was “You’ll believe a man can fly.” That was how low the bar was for visual effects in 1978. Now, of course, it’s more like you’ll believe the guy from Goonies can play an 8-foot purple alien warlord, Will Smith can play opposite his younger self, and you’ll believe an actor hasn’t actually been dead for 64 years.

Earlier this month, filmmakers Anton Ernst and Tati Golykh revealed plans to digitally “cast” James Dean in their new film Finding Jack. Yes, the same James Dean who perished in an auto accident in 1955, and who was last seen onscreen in the 1956 film Giant.

Of course, Ernst and Golykh aren’t breaking new ground here. The 2016 film Rogue One: A Star Wars Story used digital effects to bring back late actor Peter Cushing – who passed away in 1994 at the age of 81 – so he could reprise his role as the villainous Grand Moff Tarkin. Other films like 2015’s Furious 7, 2000s Gladiator, and 1994’s The Crow used digital trickery to compensate for the untimely death of an actor, but Rogue One was different. This was bringing back someone who had been gone for decades. This wasn’t just sleight of hand to get a project over the finish line. This was cheating death. Naturally, the practice doesn’t sit well with everyone.

“There is a worry among some actors that they are going to be fully taken over by the CG world, but I don’t know,” says Martyn Culpitt, visual effects supervisor at Image Engine, the FX house that has been consulted about the VFX for Finding Jack, and which boasts a resume of effects-heavy films including Logan, Spider-Man: Far From Home, John Wick Chapter 3, and Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald. “I think there’s always going to be a need for the emotion and for what an actor brings. That sense of connection. Even for digital humans, you’re still going to need a human to drive those moments. Look at something like Gemini Man – that performance is driven by a human, not technology.”

The Rights Question

Martial arts legend Jet Li said in an interview for Chinese television that he turned down a role in the 1999 sci-fi classic The Matrix because he would have to be digitally scanned, and he feared the loss of ownership of his own talents. “It was a commercial struggle for me,” said Li, “They wanted to record and copy all my moves into a digital library. By the end of the recording, the rights to these moves would go to them. I was thinking. ‘I’ve been training my entire life. And we martial artists could only grow older. Yet they could own [my moves] as an intellectual property forever.’ So I said I couldn’t do that.”

Similarly, Robin Williams has his name, likeness, and even signature entered into a trust that restricts usage for 25 years after his death, mostly to avoid situations that befell the likes of icons Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire, who ended up posthumously hawking chocolate and vacuum cleaners for ads.

California, naturally, has put forth extensive legislature regarding the use of an actor’s likeness after his or her death. The state passed a law in 1984 establishing the postmortem right of publicity for 50 years after an actor’s death. The law was a response to a court ruling that Bela Lugosi’s heirs had no power to prevent the use of his image in Dracula merchandise. At the urging of the Screen Actors Guild, the legislature has since extended the right to 70 years.

“The issue for us is straightforward and clear,” a SAG-AFTRA spokesperson said at the time. “The use of performers’ work in this manner has obvious economic value and should be treated accordingly. This is why we fight around the country, state by state, for strong right of publicity protections for performers. The digital recreation and use of performers in audio-visual works is in the vanguard of our policy efforts to protect performers.”

Of course, this only protects actors who lived and worked in California. In the UK, where Cushing lived and died, there is no such law. However, Lucasfilm did reach out to his estate to establish permission before embarking on Rogue One despite having ownership of the character likeness. In fact, Joyce Broughton, Cushing’s former secretary who now oversees his estate, even attended the London premiere to see the finished product in action.

“The digital rights and security aspect of the industry is so rock solid these days,” says Shawn Walsh, visual effects executive producer and general manager for Image Engine. “There’s a huge amount of legal architecture around the usage of anything that is acquired for any type of film or television. So there really isn’t much to worry about in that regard.”

How They Do It

Walsh understands that there can be some negative feelings around the digital resuscitation of a deceased actor, but he’s not interested in, say, using Astaire’s dance moves to sell Dirt Devils.

“I think you’re going to see more use of digital actors or digital facsimiles of actors simply for expanding the ability of filmmakers to do what they want to do,” says Walsh. “A lot of this is simply coming from the expanding world of filmmaking. One of the things about visual effects in general is that if the filmmakers were able to capture in camera live all of their creative dreams, they would. But visual effects is there for all the things they cannot. What we’re doing with digital humans is essentially enabling filmmakers to go beyond what they’re capable of capturing in camera.”

In order to execute a seamless digital performance, the Image Engine crew needs to consume as much data as they possibly can, whether the actor is available or not. Finding Jack may present a chance to step into some unchartered territory for the FX house.

“We’ve never created someone who wasn’t around before,” says Culpitt. “But we have created people who are around but not necessarily available. A lot of it is studying the actor, and the role they play within the movie. A prime example of that is the Paul Walker work that they did in Furious 7. Obviously he passed away, so they were digitally creating him from various footage and stuff. But I know that they had spent so much time researching and finding every single image and detail they could from his previous movies and performance. Because within Furious 7, he wasn’t Paul Walker, he was Brian O’Conner. He was playing the character, not being himself. So they had to build a performance that was based on a character, not just the actor.”

Culpitt points to how that production utilized Walker’s actual brothers as stand-ins, in order to base the digital recreation on something tangible. “You need that kind of base shape and performance of a human, and then we use something called the FACS system – and it’s all about the individual movements of a person’s face. It’s around 90 individual shapes and combinations of shapes and it will give you the ability to make someone move and speak.”

In order to avoid the “uncanny valley” effect, Culpitt and his team actually create full digital eyeballs that sink into carefully scanned and recreated flesh so that that move and react and – most vitally – reflect light in the same way real eyeballs do. “If you don’t have the eyes,” says Culpitt, “You don’t buy them as a human.”

While much of the attention is placed on the digital character, equal attention must be given to the environment around them if the FX is going to really trick the audience. Culpitt explains that, for sequences like the “forest fight” in Logan, they used a Lidar (which stands for Light Detection and Ranging) device to scan the surrounding area to be able to position the digital characters in a realistic way.

“The Lidar spins around and uses lasers to capture the environment where they’re doing the shoot,” says Culpitt. “And we did that for the whole forest sequence in Logan where he’s running through attacking all the guys – for that to work we needed that whole environment so we could track the position of the trees and the shadows falling across his face. So it’s all true and based on what’s actually there.”

While it seems nearly impossible that the digital James Dean will be allowed to just blend in and give a performance, given the hot takes and initial repulsion coming out of Hollywood immediately following the news of Finding Jack, the team at Image Engine wouldn’t approach the project like it’s a marketing gimmick. In fact, they’d be OK if you didn’t notice them at all.

“The most successful execution of visual effects is when nobody notices that we’ve done something,” says Walsh.