The mission changes for Charlie Company seconds after the soldiers roll off the base. The dreary night patrol around Balad, a shambling Shi’ite town in north-central Iraq, has just been canceled. It’s time instead to hightail it west, to the Sunni neighborhood of Ad Duluiyah. “Alpha Company is taking direct fire,” a voice crackles over the radio in First Lt. Brian Feldmayer’s Humvee. “I need you to expedite.”

Feldmayer, a 24-year-old Virginian with the smooth cheeks of a teenager, tries to straighten out a smile of excitement and nervous anticipation. He stares into the glowing touchscreen at his left elbow. The Army calls this system Blue Force Tracker, or BFT. It’s a militarized version of an automotive navigation aid, enhanced to track-and communicate with-other coalition vehicles. Firmly tapping the screen with his gloved fingers, Feldmayer calls up the grid coordinate just radioed to him and marks it with white crosshairs. Zooming out, he studies the roads leading there. He plots a course, then radios the rest of his patrol-two tanks, three more Humvees and an Iraqi Army Nissan truck-with orders to haul ass.

It doesn’t take long for Feldmayer to regret it. Nobody on the patrol knows the roads, and he’s wary of getting lost. Ordinarily, on his terminal, he should be able to track Charlie’s other BFT-equipped vehicles and follow the route they’re taking. But the satellite signal that feeds BFT is weak tonight. And the lieutenant doesn’t exactly trust the system’s maps: It can take the Army’s cartographers up to a year to update them; in Iraq, a lot can change by then.

Feldmayer curses loudly. He calls his command post for help, but he hears only static.

This wasn’t how the 75-man Charlie Company was supposed to operate. It’s part of the Army’s first “digital division,” the Ft. Carson, Colorado-based Fourth Infantry Division (4ID), outfitted with the military’s latest gear: new tanks, firearms and armored vehicles, but also flying reconnaissance drones, advanced sensors, electronic jammers and battlefield data networks. All of which should make the 4ID a model for the Pentagon’s vision for the future of combat–“network-centric warfare.” With the right technologies, soldiers should be able to communicate better and have a clearer picture of the battlefield. Their movements become lightning-quick and lethally effective. Think of it as combat on Internet time.

Dangerous Gaps

Every war becomes a proving ground for new tactics and new technologies. Battleships rose to prominence in World War I; tanks and bombers determined the course of World War II; Vietnam brought air power definitively into the Jet Age. The current conflict is no different. The Pentagon began this war believing its new, networked technologies would help make U.S. ground forces practically unstoppable in Iraq. Slow-moving, unwired armies like Saddam Hussein’s were the kind of foe network-centric warriors were designed to carve up quickly. During the invasion in March 2003, that proved to be largely the case-despite most of the soldiers not being wired up at all. It was enough that their commanders had systems like BFT, which let them march to Baghdad faster than anyone imagined possible, with half the troops it took to fight the Gulf War in 1991. But now, more than three years into sectarian conflict and a violent insurgency that has cost nearly 2,400 American lives, an investigation of the current state of network-centric warfare reveals that frontline troops have a critical need for networked gear-gear that hasn’t come yet. “There is a connectivity gap,” states a recent Army War College report. “Information is not reaching the lowest levels.”

This is a dangerous problem, because the insurgents are stitching together their own communications network. Using cellphones and e-mail accounts, these guerrillas rely on a loose web of connections rather than a top-down command structure. And they don’t fight in large groups that can be easily tracked by high-tech command posts. They have to be hunted down in dark neighborhoods, amid thousands of civilians, and taken out one by one.

Even in the supposedly wired 4ID, it can take years for frontline soldiers to benefit from the technologies that high-ranking officers quickly take for granted. The finicky, incompatible equipment that’s given to the infantrymen and tank drivers in Charlie Company-the guys who are spending this cold, wet February night on the front-is primitive in comparison with the gear at the sprawling military base outside of Balad, where battalion-level commanders oversee the 300 troops in Charlie and three other companies. There, things are beginning to work like the network-centric theorists predicted, with drone video feeds and sensor data and situation reports flying in constantly. But to the guys in Charlie Company, this technological wizardry and the Pentagon’s futuristic hypotheses seem awfully far away.

There is a simple, but significant, reason why: Bringing frontline infantrymen into the network isn’t as easy as wiring up a headquarters. Battlefield gear has to be wireless, durable, secure, and completely effortless to use in the chaos of combat. The network is slowly expanding to meet the grunts. But the Department of Defense’s lumbering process for buying new equipment still virtually ensures that ground-level soldiers won’t be linked-in until early next decade. “The fog, friction and uncertainty of war are still there, same as always,” says retired Marine Col. T.X. Hammes, considered one of the leading authorities on counterinsurgency. “This net-centricity helps some, but it only goes as far as the battalion [the command echelon above the companies that do the actual fighting]. After that, these guys are on their own.”

Blind Spots and Incompatible Systems

Feldmayer radios the tank at the rear of his patrol and orders it to the front of the convoy. It’s the latest M1A2 Abrams, one of the most advanced tanks in the world, equipped with new night-vision sensors, thicker armor and BFT’s older (and, counterintuitively) more feature-packed cousin: Force XXI Battle Command Brigade-and-Below, or FBCB2. First built in the early 1990s for Cold War-style conflicts, where armies are tightly bunched together, FBCB2 relies on a classified radio band to communicate. BFT, designed later for more-dispersed, unconventional warfare, uses more-open satellite transmissions; troops can share information at greater distances, but they can’t get the kind of secrecy that FBCB2 provides. The Army is working on a bridge between the two systems so that they will be able to share some basic information, but for now they are mostly incompatible. Feldmayer won’t be able to see where the tank is leading them, and he won’t be able to use FBCB2’s Instant Messenger-like tool to quickly relay commands. He won’t have access to any of the communications links that increase what the Pentagon calls “situational awareness” and that ultimately power network-centric warfare. If the navigation systems were working, every vehicle could split up or speed ahead if an attack came, without getting lost. But today they will all have to follow the tank’s taillights in a neat line, just as it was done in 1944.

Charlie Company takes off, racing toward the fight at Ad Duluiyah. Careening around traffic circles, blowing past checkpoints, the company is primed for combat: weapons loaded, 120-millimeter cannon shells rammed into breaches. Radio-frequency jammers form a protective bubble around the convoy, keeping remote-controlled roadside bombs from detonating. “They better have that shit wrapped up by the time we get there,” Feldmayer shouts, “or we’re going to blow some shit up!”

Then, suddenly, the lead tank

lurches to a halt. Through roiling clouds of dust, illuminated by the tank’s headlights, Feldmayer sees a pile of concrete and earth. The lead tank’s fancy navigation system has just led them into a roadblock, too tall for the vehicles to climb. A dozen soldiers curse in unison.

By the time Charlie gets to Ad Duluiyah, 45 minutes later, the shooting is over. A dozen Humvees and Bradley fighting vehicles line a muddy road leading to a rickety pontoon bridge that’s nearly swamped by a surging stream. And all those soldiers’ chatter is creating cacophony over the Single Channel Ground and Air Radio System, or Sincgars, the radio system connecting the Army’s fleet of helicopters and ground vehicles. It’s the buzzing, chirping sound of information overload.

An officer from Alpha Company walks over to explain what’s going on. Alpha was following up on leads about a stolen Iraqi police truck when the soldiers spotted a suspiciously large gathering of cars in front of a single house. When Alpha got close, Iraqis spilled out, sprinting for their cars and shooting off tracer rounds. Alpha didn’t have enough men to pursue.

Now the idea is to start searching houses, one at a time, for insurgents. Charlie Company is assigned the northwest side of the stream. Feldmayer tells his tank commanders to use their infrared sights to watch over the foot patrols. Taking a last glance at his BFT, eyeballing the digital representation of the dark, foreboding neighborhood he’s about to penetrate, Feldmayer mutters, “Don’t need this anymore,” and switches the system off.

Inspired by Wal-Mart

The Pentagon’s pursuit of network-centric warfare began in the info-tech boom of the 1990s-largely influenced by, of all things, Wal-Mart. Ultra-wired retailers like that knew tons about their customers’ needs and habits, and their suppliers’ capabilities. And that helped the companies become more profitable, with less inventory and fewer employees, than their more-traditional rivals. This kind of “information superiority,” Admiral Arthur Cebrowski and Pentagon scientific adviser John Garstka argued in a 1998 issue of the Naval Institute’s Proceedings, would allow the military to streamline similarly. Fewer troops could cover wider areas when networked. Tanks and ships could carry less armor and fewer guns, because they would know exactly where their enemies were. Lower-level commanders could make key decisions. Conventional armies wouldn’t stand a chance.

The Army’s leadership quickly embraced the idea. In 1999 Gen. Eric Shinseki, then Army chief of staff, accelerated an overhaul of the organization, primarily along the network-centric model. Every soldier and every machine would be tapped into a giant, wireless intranet for combat. Presidential candidate George W. Bush embraced the concept too, during the 2000 election. And when Bush entered office, Cebrowski was installed as the director of a new Pentagon department: the Office of Force Transformation.

Then came the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. The network wasn’t done, but the slices that had been set up-like BFT, which enabled American commanders to see one another’s locations-helped to decapitate Saddam’s regime almost instantly. Individual troops still had trouble communicating with one another; some Marine squad leaders were forced to use five different radios to share information. In the early days of the Iraq war, it didn’t seem to matter.

The gear was clearly saving lives. The number of friendly-fire incidents that plagued U.S. troops during the first Gulf War dropped significantly, for example, thanks to the new, networked equipment. In November 2004, 10,000 marines participated in the assault on Fallujah. With drones watching overhead and commanders communicating better, not one marine was killed by friendly fire. Faith in the new technologies ran so high, the Pentagon decided to cut troop levels in key areas. This part of Iraq was patrolled by 1,200 soldiers in 2004; now, a single battalion -300 troops-covers the same area.

The Situation Room

At the battalion command post outside Balad, cables spill along the floor like the guts of an electronic beast. Flat-screen monitors display both grainy black-and-white and color surveillance footage, as many as 20 feeds at a time. Tower-mounted cameras, unmanned spy planes, even Air Force and Marine Corps fighter jets toting infrared targeting pods supply the images. It’s an absolute torrent of information for the battalion’s rumpled intelligence officer, Captain Pete Simpson, and his team of five analysts. With it, they keep watch over more than 1,000 square miles of Iraq from their desks.

A few years back, a division headquarters supporting 10,000 or 20,000 troops might not have had access to this much real-time footage. “We’ve got more stuff than we have any right to,” Simpson jokes. But he can do more than get views from overhead. Thanks to the Sincgars radios, junior officers like him can quickly coordinate ad hoc missions with whatever jets and helicopters happen to be in the air-and order them to attack. “When I was a junior officer, this happened at the corps level,” says Simpson’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Jeffrey Vuono, referring to an Army unit with 20,000 to 40,000 men. “Now we’re doing it at the patrol level.”

The air-ground collaboration is one of dozens of different ways that

network-centric tools are slowly starting to rejigger the military’s hidebound hierarchies. In the Gulf War, the various armed services didn’t talk to one another much, except at the highest levels. That’s partly why there was a six-week air campaign and then a ground attack. During the 2003 invasion, the air and ground assaults struck at once.

But one of the most powerful tools in battalion command posts like these, notes Garstka, the network-centric theorist, may be one of the simplest: a Web browser, so junior officers can log into secure online forums. There captains and lieutenants can swap tactics, well before they appear in printed field manuals. This is critical in a place like Iraq, where insurgents’ strategies change almost daily. When First Cavalry Division captain Chris Manglicmot first started seeing car bombs in his northeastern Baghdad sector, he turned to the division’s collaborative site, Cavnet, for advice. Spread out your checkpoint, he learned, so the bombers don’t have a central target. Look for vehicles that ride heavy and low. Watch for cars that drive aggressively, with shades pulled over the windows. There could be a bomb inside.

Paper, Not Pixels

Picking his way through the crumbling houses of Ad Duluiyah, Feldmayer is tied to the American grid by only the thinnest of threads. There’s no way for him to get on any collaborative Web site from here. Most of his men are out of reach, scattered throughout the town. Many don’t have radios; traditional Army fighting doesn’t call for individual soldiers to be separated from their squad very often.

Feldmayer follows the Iraqi soldiers he’s been teamed with across a dark, muddy, pothole-riddled yard. A locked gate bars the way to a group of houses. One of Feldmayer’s U.S. soldiers blasts it open with a shotgun, and the men spill into the yard in front of a large dwelling. Soldiers crowd the front door, pounding with closed fists and yelling in Arabic. Women and children dart around corners and disappear into rooms. Tired men scurry outside, obviously spooked.

Feldmayer doesn’t like the aggression. “Just take it easy,” he tells the Iraqi troops through the patrol’s interpreter, to the civilians’ palpable relief. One of the men gathered in the yard gestures to the lieutenant. Feldmayer grabs the interpreter and shakes the Iraqi man’s hand. “Salaam,” Feldmayer says. The three put their heads together, muttering in English and Arabic.

Suddenly Feldmayer cuts off the conversation and urges the man and the interpreter around a corner. “He says he knows who the bad guys are around here,” Feldmayer says. The interpreter takes notes as the informant rattles off names and addresses. If the Pentagon’s vision of networked forces were realized here, he would be typing into a handheld computer, wirelessly connected to a network. The names would immediately be cross-checked with databases of known guerrillas and disseminated to local commanders. But for now, the patrol’s interpreter writes down the Ad Duluiyah suspects on paper, using a pencil.

It’s at this point, just beyond the edge of the American network, where the guerrillas are best connected. Using disposable cellphones, anonymous e-mail addresses at public Internet cafs, and “lessons learned” Web sites that rival Cavnet, disparate guerrilla groups coordinate attacks, share tactics, hire bomb makers, and draw in fresh recruits. It’s an ad hoc, constantly changing web of connections, so it’s hard for U.S. spooks to know where to listen in next. It also lets the insurgents keep a loose command structure, without much hierarchy-just like the network-centric theorists call for. Even if their communications are compromised, only a small cell is exposed, not the entire insurgency. “They’re more effectively networked than we are,” says Hammes, the guerrilla-war expert. “They have a worldwide, secure communications network. And all it cost them was two dinars.”

To compensate, some American soldiers are buying their own gear: $50 Motorola walkie-talkies, so they can talk to their squad mates; $160 Garmin GPS receivers to make up for FBCB2’s gaps. It’s quicker than waiting for the wheels of the Pentagon bureaucracy to turn. At the Defense Department, there’s widespread recognition that it needs to get its frontline soldiers wired up. Pencil and paper just won’t do.

The technologies being readied, however sluggishly, could be a huge help to soldiers on patrol, like Feld-

mayer. The Warfighter Information Network-Tactical, or WIN-T, is a mobile wireless Internet for combat, scheduled to deploy early in the next decade.

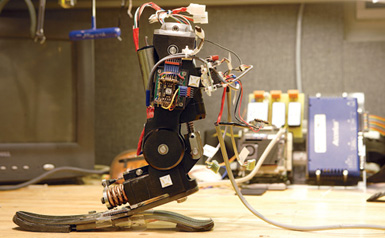

Also in the next decade, the Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) should start replacing the military’s tangle of analog radios with compatible digital models. Another project, Land Warrior, is a new set of soldier uniforms, packed with electronics and communications gear. Once it’s completed-perhaps by 2008-FBCB2-style information will appear on more than just a Humvee screen. It will flow to the infantryman, through a monocle-like display mounted to his helmet. Every soldier will see where his fellow fighters are.

If only these programs were progressing as planned, but each has been bogged down by lengthening to-do lists and sets of system requirements. JTRS recently went through a massive reorganization after billions of dollars were wasted. Land Warrior, started in the mid-1990s, is years behind schedule; managers are hoping that a 440-soldier test this summer will put it back on track. For now, all Army acquisition chief Lt. Gen. Joseph Yakovac will say is that “we continue to have that vision” of a networked infantryman.

Mission’s End

After hours of barreling down highways, blasting open locked gates, and pressing terrified Iraqis for information, Charlie and Alpha companies trickle home from Ad Duluiyah. Feldmayer’s Humvee is the last to leave, towing the sniper section’s broken-down truck. Feldmayer stares into the cold dark of the early morning. His shoulders sag. In his pocket, he carries the insurgent list he coaxed out of the Iraqi informant. His sergeant gripes about missed firefights. But Feldmayer just nods, his arm draped on the blank screen of the BFT.

Noah Shachtman is the editor of DefenseTech.org_. David Axe has covered the Iraq war for the Village Voice and the Washington Times._