PART 1: FRANCE AND CANADA

A french former paratrooper with no family ties, michel fournier almost made Le Grand Saut. Then

he balked.

By Bruce Grierson

In the middle of the plate-flat Canadian prairie, not far from where writer Raymond Carver hunted geese, a flurry of activity broke out last September around a small, rural airfield. Here was ground zero for French skydiver Michel Fournier’s audacious attempt to ride the pressurized gondola of a helium balloon to 130,000 feet-the cusp of space, the highest anyone has ever gone without a rocket-and topple out earthward. Diving into a near-perfect vacuum he would, in 31 seconds, hit 670 mph and slam into the sound barrier, the first human being to do so with his body. If all went well-a big if-he’d free-fall for just under 5 minutes before his chute delivered him to the ground.

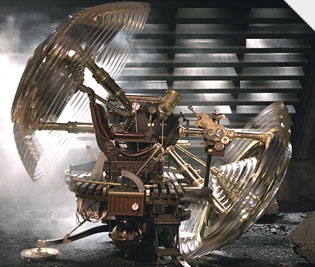

The helium truck had moved into position in the adjacent canola field near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. The doors to a hangar yawned open, revealing a phone-booth-size, airtight gondola ready to be moved onto the flatbed launch truck. An ambulance stood by in the event of catastrophic failure of any components-the balloon, the gondola, the parachute couplings, the oxygen supply, the partial-pressure suit, the supple oversuit designed to shield Fournier from freezing atmospheric temperatures. After two weeks of dashed hopes, it looked as if Le Grand Saut -The Big Jump-just might happen. All the ghoulish handicapping of Fournier’s chances of coming down alive had ceased.

The man dubbed Monsieur Mach One paced about in his skin-tight, military-green spacesuit whistling Que Sera, Sera, looking vaguely amphibious. He was walking a bit stiffly. Could’ve been the suit-they’re notoriously uncomfortable. Could’ve been the rectal probe he wore to monitor his internal pressure and temperature as the capsule rises beyond the atmosphere under an ultrathin polyethylene balloon envelope that would swell, in that rarefied environment, to 18 million cubic feet. And though you’ll never find more sangfroid in one 5-foot 7-inch package, it could have been nerves.

Then the bad news. The wind had changed direction and was picking up. The launch was postponed again. Fournier’s entourage huddled and kindled some locker room mojo. “Michel hip hip hoorah! Hip hip hoorah!” Fournier looked a bit embarrassed: “Save it until after I jump.” He was working hard to contain his emotional investment in the moment. The past 14 years of his life-which have seen him log more than 8,300 skydives and set the French altitude record of 39,000 feet-had sharpened to a point.

Ever since the 1989 cancellation of S38-a French Ministry of Defense initiative designed to see whether a parachutist could safely descend from 125,000 feet (roughly the height at which the space shuttle Challenger exploded)-Fournier has been obsessed with the idea of a record-breaking, stratospheric jump. At the time he was a paratrooper in the French army, but he left the military in 1992 and sold everything: his house, his furniture, his car, his war medals and his arms collections. With the cash he bought the defunct S38 hardware and privately carried on what the Ministry of Defense had started.

By 1997 Fournier was training seven days a week, leading up to the announcement in September 2000 that he was ready to make his jump in the Provence countryside. But when the French government deemed the area too densely populated, Fournier chose Saskatchewan; it was more remote and had plenty of sunshine and a favorable jet stream during the spring and fall weather windows. The son of working-class parents, Fournier had only an elementary school education when he joined the military in 1963. He holds a view of the world and of his leap that seems uncomplicated by nuance. Why is he doing it? Pour la defie, Fournier says: for the challenge. For the science. But mostly for the record.

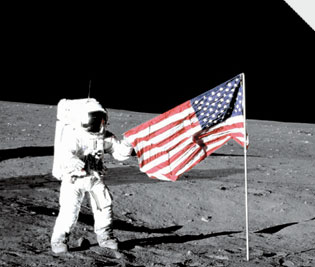

That record still belongs to Air Force pilot Joe Kittinger Jr., who, in 1960, completed the highest-ever human jump, from 102,800 feet. Kittinger accomplished this on his third ultrahigh-altitude leap over the New Mexican desert, the pinnacle of the U.S. Air Force’s Project Excelsior program, which was designed to test whether pilots could survive high-altitude bailouts. But an earlier attempt was close to catastrophic. Kittinger was nearly killed when his drogue, a small stabilization parachute designed to stop his body from spinning and keep him pointed feet-down, opened prematurely and the canopy line twisted around his neck. He eventually blacked out from centripetal G forces caused by spinning but regained consciousness as soon as his reserve chute opened. Kittinger’s subsequent jumps went more smoothly but were by no means without complications. On the dive that established the world record, Kittinger’s glove ruptured, the lack of pressurization causing his hand to swell to nearly twice its size. But he alighted safely, having reached 614 mph (just under the speed of sound at his altitude).

At 58, Fournier is nearly 30 years older than Kittinger was when he made his record dive. But Fournier’s age-and that of his American rival, Cheryl Stearns, who is 47, not to mention their top crew members, who are also riding the tail end of middle age-is actually an advantage. Aside from physical strength, a jump this daring requires consummate knowledge and experience. Many of the things that could go wrong, deadly wrong, might baffle a less seasoned skydiver. Besides, trying to keep up with Fournier during his 10-mile morning run (he’s a marathoner and a pentathlete) quells any doubts that he’s up to the task. He’s compact, vaguely resembling Robin Williams. He’s both stoic and boyishly animated, like a French circus mime. An individualist-he’s divorced, no children, no brothers or sisters-Fournier is on his own trajectory.

“Michel owes no family-he’s just by himself,” says Jean-Franois Clervoy, a French astronaut who has flown on the space shuttles Atlantis and Discovery and was himself a candidate to make the S38 jump before it got shelved. The lack of distractions, Clervoy says, explains how his friend could focus so single-mindedly on this project-hiring technicians, overseeing every aspect of the hardware development, meeting with investors to raise money. And submitting to punishing tests.

To get his hands accustomed to working in the cold, so he can open his parachute and handle its command strings even if his gloves fail to insulate adequately, Fournier practiced plunging them into a garbage can full of ice water until he could leave them there for 30 minutes. He spent long hours in pressure chambers at the equivalent of 65,000 feet above sea level. In Grenoble, France, he sat in a thermal chamber chilled to minus 55