A tiny tropical flower is challenging a longstanding model for plant evolution. According to researchers at the Field Museum in Chicago, an oddball member of the lipstick vine family evolved to attract more pollinators before spreading to other parts of the world, and not the other way around.

“It was really exciting to get these results, because they don’t follow the classic ideas of how we would have imagined the species evolved,” explained Jing-Yi Lu, a botanist and coauthor of a study published today in the journal New Phytologist.

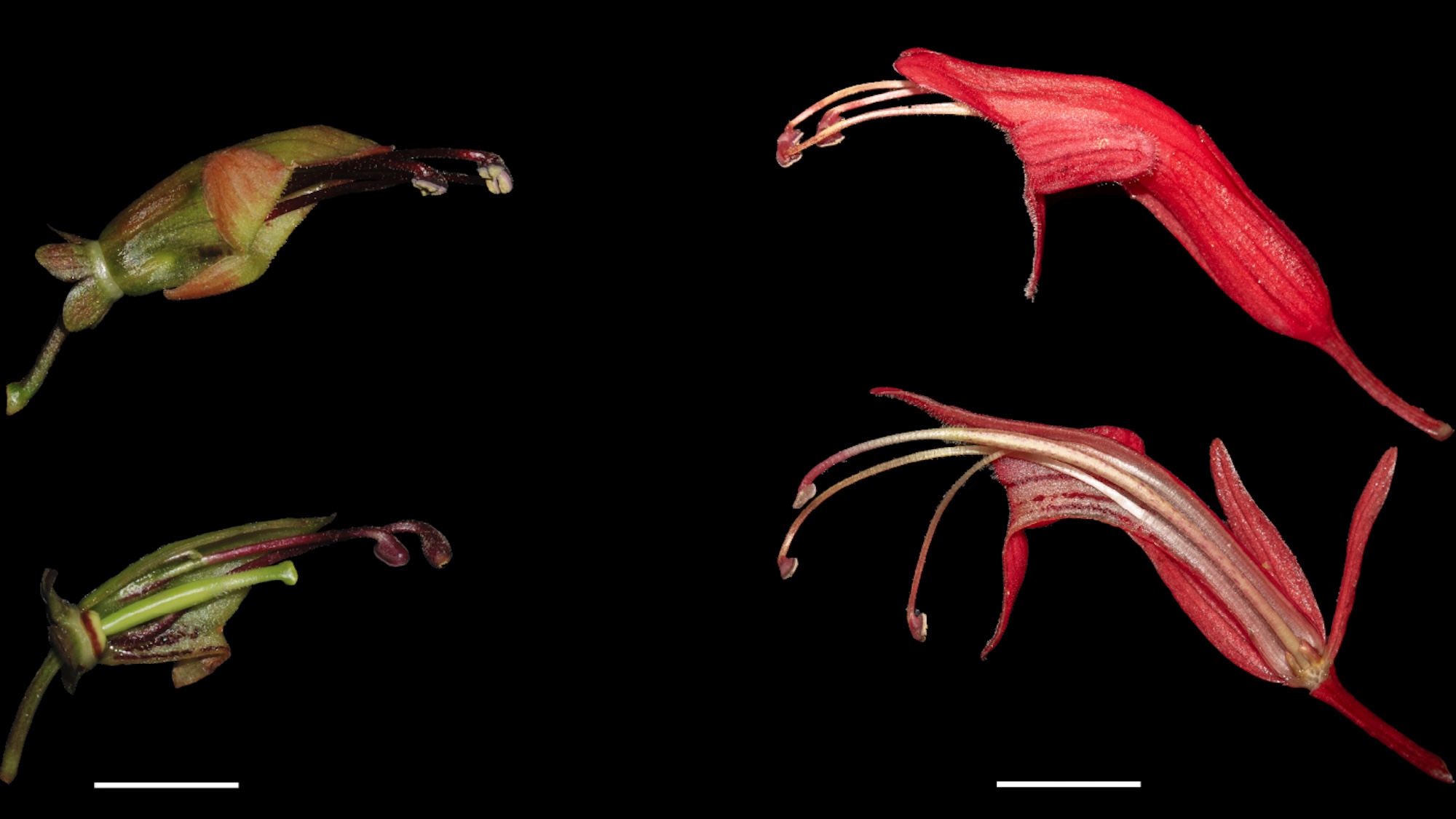

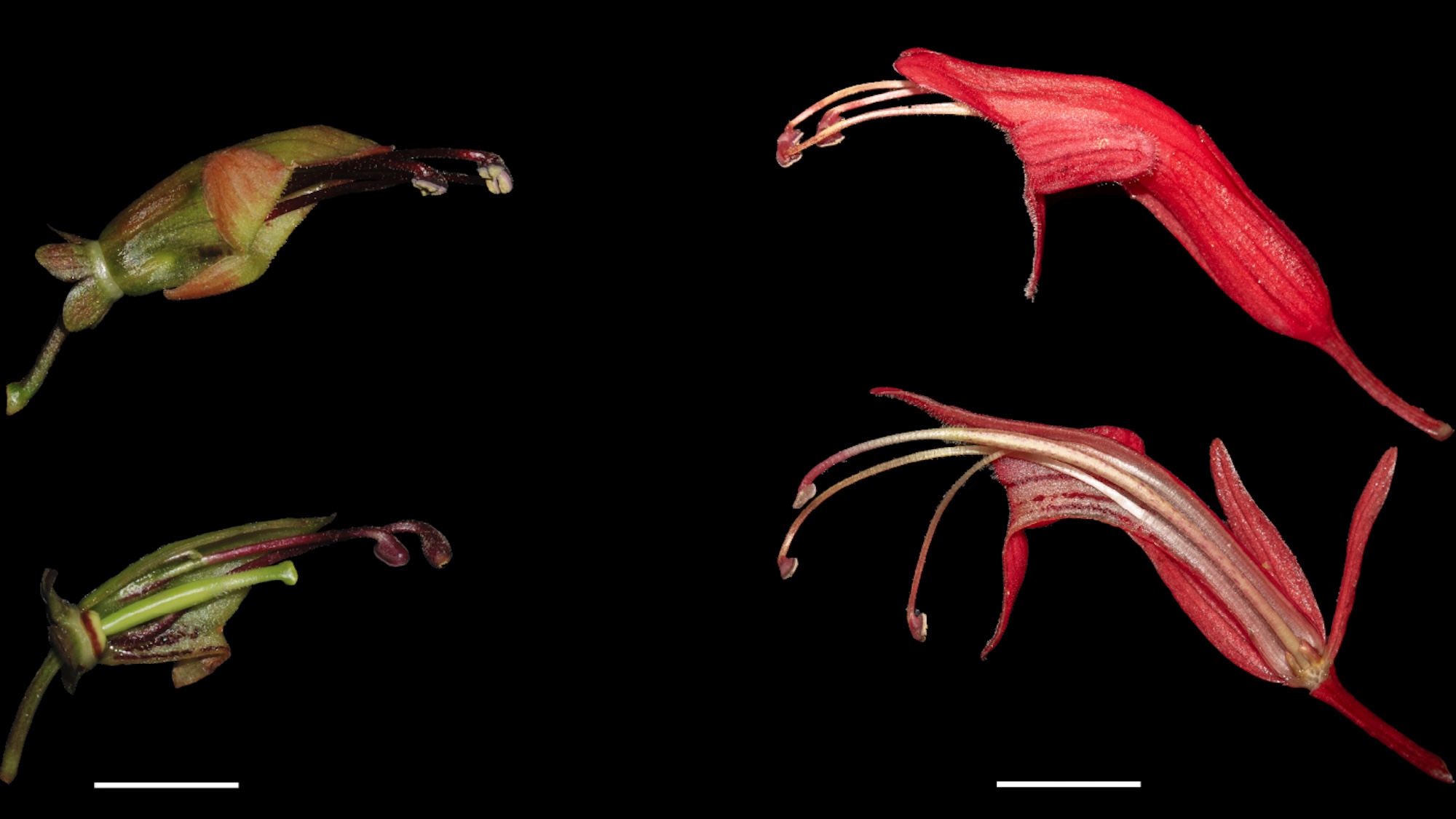

Most lipstick vines look like their name implies: lengthy plants featuring vibrantly red, tubular flowers. Identifiable across Southeast Asia, their nectar primarily attracts longbeaked sunbirds, who in turn help spread pollen for propagation. In Taiwan, however, one lipstick vine species known as Aeschynanthus acuminatu looks dramatically different from its relatives. Instead of crimson flowers, A. acuminatu possesses much shorter, wider flowers with a greenish-yellow coloration.

“Compared to the rest of its genus, this species has weird, unique flowers,” said Lu.

Because of this, A. acuminatu is far more suited for Taiwan’s shorter-beaked birds. It’s a good thing, too—sunbirds aren’t found anywhere on the island. That said, the yellow-green lipstick vines are also found on the mainland. Knowing this, Lu and his colleagues began to wonder where the plant evolved first.

“At the heart of our study is a question of where species originate,” said Rick Ree, a study coauthor and curator of the Field Museum’s Negaunee Integrative Research Center. “There must have been a switch when this species evolved, when it went from having narrow flowers for sunbirds to wider flowers for more generalist birds. Where and when did the switch occur?”

Many botanists might assume the answer could be found in the Grant-Stebbins model. Utilized in the field for over half a century, the Grant-Stebbins model asserts that plants usually evolve different species after they migrate into new regions featuring different types of pollinators. With this in mind, it stood to reason that A. acuminatus originated in Taiwan to accommodate the island’s short-beaked birds. However, the researchers were surprised by what they saw after using lipstick vine DNA samples to assemble a series of family trees.

“The branching patterns on the family trees we made revealed that the A. acuminatus plants on Taiwan descended from other A. acuminatus plants from the mainland,” said Ree.

This means that for some reason, the shorter, greener lipstick vines evolved in a region with plenty of sunbird pollinators. If true, then this contradicts the Grant-Stebbins model—but researchers have a theory about how this could happen.

“Our hypothesis is that at some point in the past, sunbirds stopped being optimal or sufficient pollinators for some of the plants on the mainland,” explained Ree. “There must have been circumstances under which natural selection favored this transition toward generalist passerine birds with shorter beaks as pollinators.”

Ree stressed that their unexpected conclusions were only reached after botanists like Lu took time to travel into the field themselves.

“This study shows the importance of natural history, of actually going out into nature and observing ecological interactions,” he said. “It takes a lot of human effort that cannot be replicated by AI, it can’t be sped up by computers—there’s no substitute for getting out there like Jing-Yi did…”