Could swappable EV batteries replace charging stations?

India is the latest of several countries to consider the workaround for fast-charging.

Over the last month, two countries have taken steps towards a technology that was once a white-whale of electric vehicle manufacturing: swappable batteries.

In a ceremony full of fog machines and flashing lights, Chinese car manufacturer Nio opened an electric vehicle battery swapping station in Norway last month. Drivers will supposedly be able to swap drained batteries in a matter of minutes. And in a budget speech for the coming year, India’s finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, laid out a vague commitment reported by Reuters: “considering the constraint of space in urban areas for setting up charging stations at scale, a battery swapping policy will be brought out.”

The opening ceremony for NIO’s battery swapping station.

In theory, the approach side steps any need for breakthroughs in battery capacity or speed. Rather than waiting to fill up a depleted battery, a driver could treat a car more like a camera or toy, swapping out the battery when needed.

But in practice, says Gil Tal, director of the University of California Davis’ Plug-in Hybrid and Electric Vehicle Research Center, battery swaps replace the challenge of fast charging with another. “The problem is that for each car on the road, you have many more batteries waiting in storage,” he says. A company could cut down on the number of batteries it kept on hand by charging them faster—but that would just displace the fast-charging costs.

[Related: What to know before you buy an electric vehicle.]

Currently, NIO is the only major operator of a passenger car battery swap network. The company plans to build 700 swap stations by the end of 2022and said in press release that it performed 500,000 swaps by mid-2020. (For a sense of scale, the South China Morning Post reported in 2017 that the country had more than 300 million vehicles on the road.)

The stations allow drivers to swap out batteries from any recent NIO electric car in about three minutes, according to the company. The company plans to open more stations in Norway this year, where it’s also selling battery subscriptions separately from the car itself.

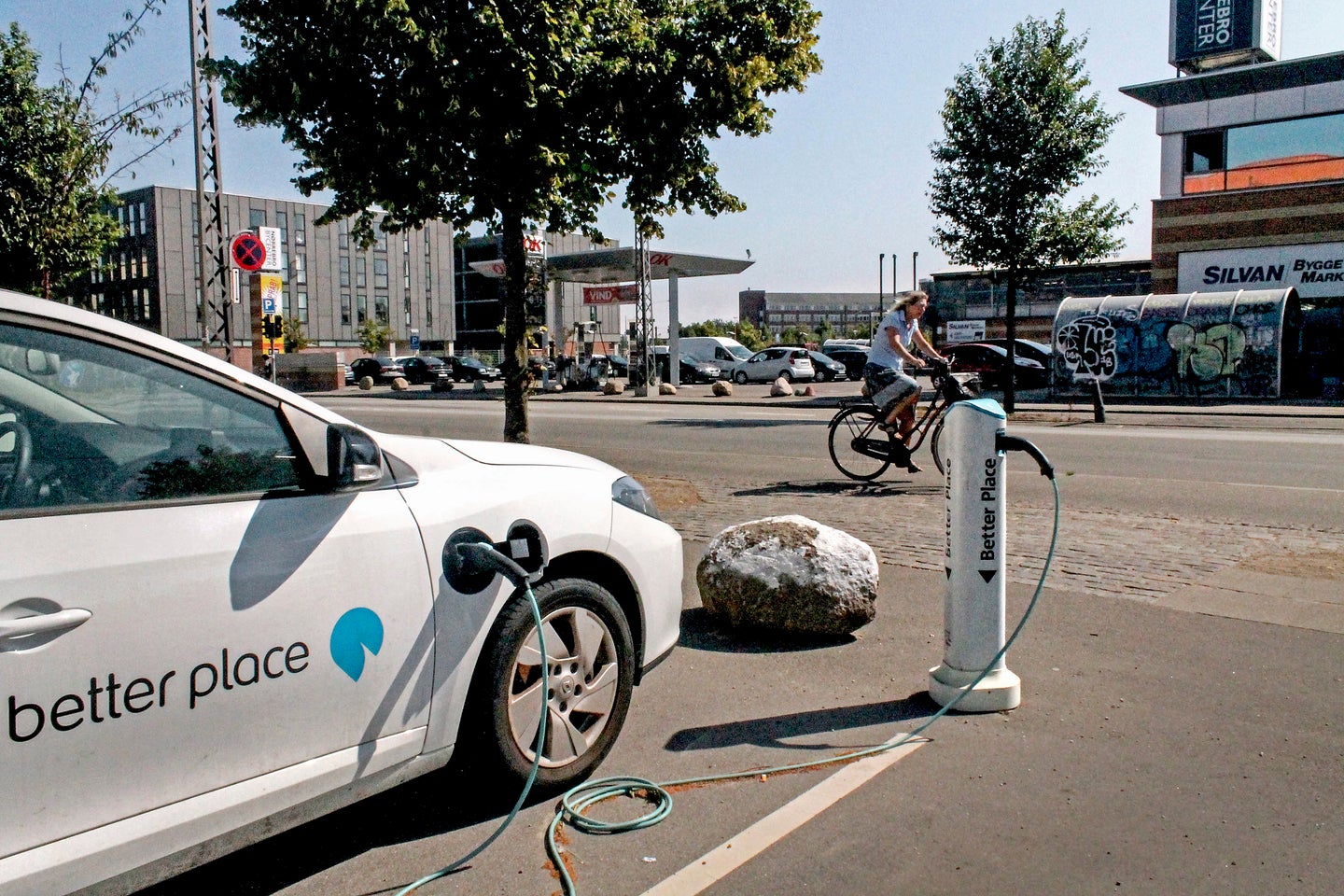

But the last major push to roll out battery swapping infrastructure, led by Israeli startup Better Place, went bankrupt in 2013 after raising more than $800 million in funding and securing tax subsidies from multiple governments. At the time, Evan Thornley, then-CEO of Better Place, argued that the economics of the business still made sense, and that its failure was largely one of execution.

A key challenge in battery swaps lies in the fact that they require buy in from car companies as well as consumers. “It’s like telling car manufacturers, you all have to have a Toyota engine,” says Tal.

The startup made more financial sense at the time because gas prices were high, pushing car buyers towards low-emissions vehicles. Meanwhile, EV ranges were limited by battery price and technology, and swapping looked like a reasonable way to address those problems. When prices fell again, the benefits to consumers disappeared.

In the meantime, alternative charging offerings appeared. EV batteries became cheaper, range expanded, and automakers began to design cars that could support fast-charging, which can add hundreds of miles of range in half an hour. On February 11, the Biden administration announced plans for a $5 billion investment in EV charging, which would prioritize fast charging stations along federal highways.

[Related: Electric vehicles are only one part of sustainable transit.]

Tesla, the world’s largest electric car seller, did experiment with a battery swap station in 2013. As they rolled out thousands of new Supercharger stations in 2016, the project quietly shut down. And after a report early in 2021 claimed that the company had invested in the technology in China, Tesla shot down the rumors. According to Shanghai news site Shine, an anonymous Tesla official called battery swapping “riddled with problems and not suitable for wide-scale use.”

It’s possible that battery swapping would be useful in some narrow cases, like fleets of vehicles all owned and operated by the same company. “It can work with a dedicated fleet that have very, very high value on time,” says Tal. “If fast charging will take half an hour and the battery swap takes five minutes, you save 25 minutes.” For a delivery company like FedEx or Amazon, that 25 minutes could be worth the cost of investing in backup batteries.

Battery swapping could also fit smaller vehicles, like e-bikes, which often already have removable batteries. Tal gives the example of someone who rides an e-bike to the office, plugs the spent battery into charge, and plugs in yesterday’s for the ride home.

The Taiwanese scooter manufacturer Gogoro, for instance, operates a network of battery stations, and claims to facilitate more than 200,000 swaps every day.

And in India, micromobility companies do seem interested. In December 2021, India’s Business Standard reported that vehicle-manufacturer Mahindra had partnered with oil company Reliance Industries to develop battery swapping technology for food delivery fleets. And the motorcycle company Hero MotoCorp announced in the spring of 2021 that it would open a network of swap stations with Gogoro.

Like lots of green technology, battery swapping is going to be useful in some cases, but not a panacea.