Hiromitsu Nakauchi is one of the most prominent stem-cell researchers in the world, and over the past few years, he’s been cruising along a path that could well result in a near-unlimited supply of healthy pancreases for humans, which could well cure some types of diabetes. Except, in his native Japan, the law has yet to catch up to his work.

Nakauchi has lately been specializing in chimeric embryos, in which stem cells from one species are implanted in another, which then grows an organ that can be harvested and implanted back in the first species. The name “chimeric embryos” suggests a sort of horrifying (or, to be fair, possibly adorable) mix of species, but that’s not really what’s going on. Instead, the aim is to induce one species to grow an organ of the other, not a combination of two species.

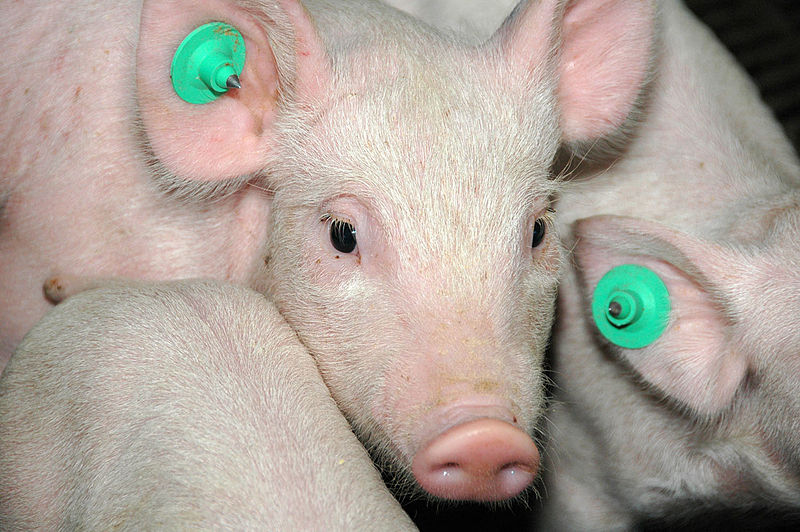

He’s done this with mice and rats; back in 2010, he successfully induced a mouse embryo to grow a rat pancreas by using rat stem cells. But the goal is human organs, so his focus has of late shifted to our friend the pig. The technique involves taking genetically engineered pig embryos that are incapable of growing their own pancreases and implanting human stem cells. The pig embryos will then grow, amazingly, a human pancreas. When the piglets are born, the pancreas is harvested, and then can be implanted into a human in need. Pigs are chosen because they’re common and well-understood, and also because their organs are of similar size to our own.

Japan currently has a ban on what’s called “in vivo” experiments, meaning “within the living.” Essentially, Japanese law forbids experiments that involve a whole, living creature, like these piglets. (“In vitro,” or “within the glass,” is permitted.) Nakauchi has for years been campaigning to change this law, and he’s making baby steps; earlier this week, the Expert Panel on Bioethics of the Council for Science and Technology Policy, Japan’s federal science advisory board, recommended the laws be changed to allow Nakauchi’s work. But that’s not the same as changing a law; even if the Japanese legislature agrees, it’ll be at least a year before the law can be updated.

According to Science, Nakauchi is considering moving his research to another country that allows in vivo experiments–like, say, the U.S., where, at Stanford, he did some postdoctoral work. The U.S. does not federally prohibit in vivo chimeric embryo research, though a few states have passed their own laws.

Chimeric embryo experiments are highly controversial; they’re easy to confuse for some kind of Dr. Moreau-type madness, but even when you’ve got a grip on what’s actually going on, it’s hard to take a firm stance on either side. On the one hand, you could well cure forms of diabetes, grow hearts or kidneys or any other organs, and legitimately save lives. On the other hand, this is wild, foreign stuff, and also involves some genetic manipulation and almost certainly some inhumane treatment of animals. (How happy are those pancreas-less piglets, really?) It’s a debate without easy answers, but one we’ll be following closely.