Samsung’s 108-megapixel smartphone camera sensor is more practical than it sounds

It's not meant to jam your phone with massive photos

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

Comparing megapixels has fallen out of fashion for the most part, at least when it comes to smartphone cameras. In fact, the iPhone XR camera boasts just 12 megapixels, and every version up to and including the iPhone 6 had just 8 megapixels. Now, however, Samsung and Xiaomi have teamed up to build a 108-megapixel sensor destined to fit inside of a future smartphone. It’s the first commercial chip of its kind to break the century mark in terms of resolution. And while it’s an impressive feat, you probably shouldn’t expect it to work just like its 100-megapixel competition which typically costs as much as a decent SUV.

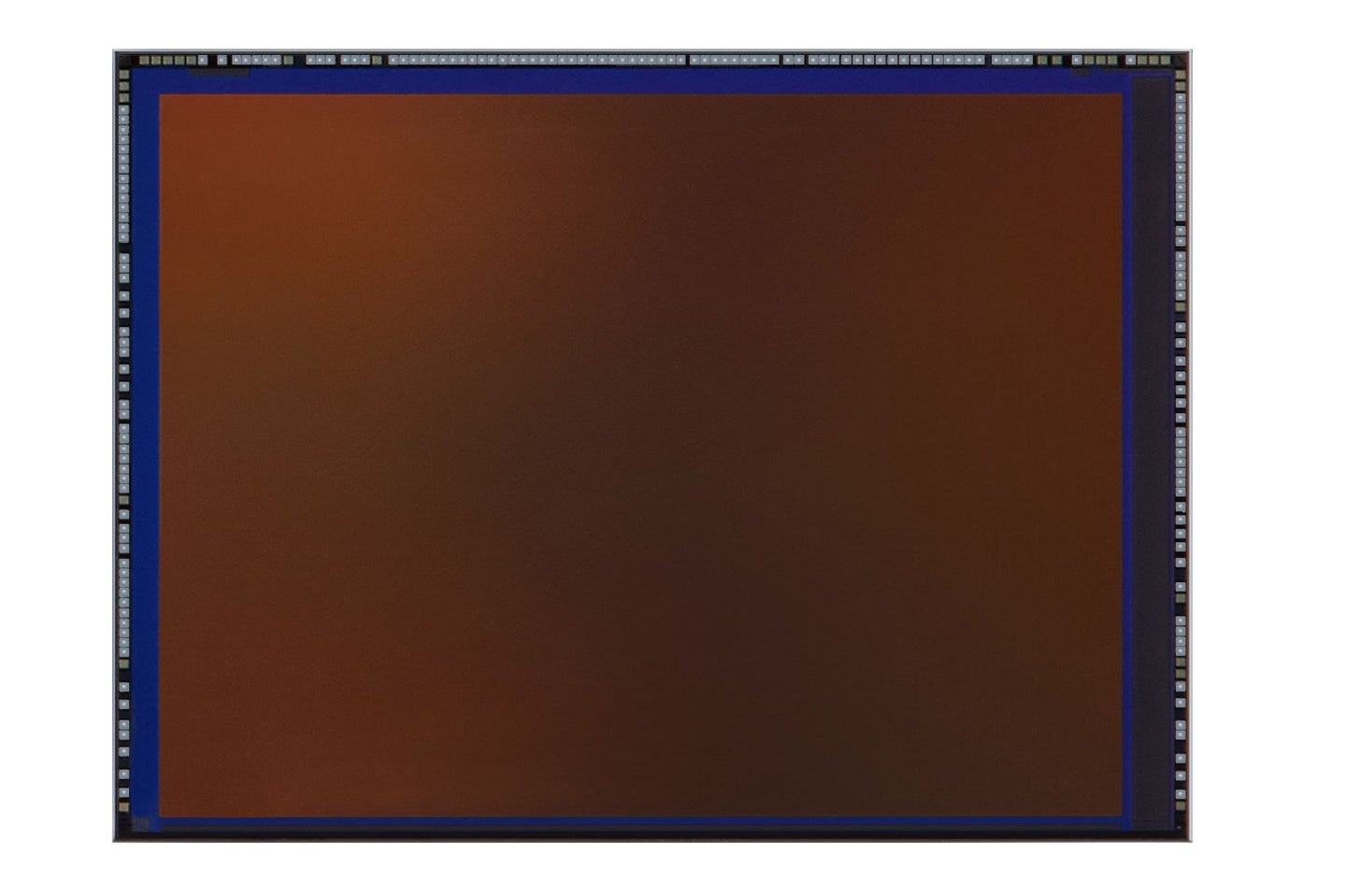

Samsung and Xiaomi’s chip is called the 1/1.33-inch ISOCELL Bright HMX sensor, which is—if you can believe it—even more complicated to decode than it seems at first glance. The 1/1.33-inch number reads simple enough, but it’s actually a reference back to a rather arcane sensor sizing standard that started in video cameras. In reality, it’s still smaller than the chip inside a camera like Sony’s RX100 VII advanced compact camera, but bigger than a typical smartphone sensor.

That extra real estate on Samsung’s chip makes space for 108 million pixels, but its ultimate goal is to use that raw data to churn out 27-megapixel images. Samsung calls this process “pixel-merging,” in which the camera groups several smaller pixels together (in this case, it’s groups of four). That allows them to act like much bigger pixels and pull in more light.

If that sounds familiar, it’s because the concept has been around for quite some time. Back in 2013, Nokia introduced the PureView 808 smartphone camera, which used a 40-megapixel sensor to churn out high-quality (roughly) 5-megapixel images by grouping 7 pixels together.

How does that tech compare to a regular 27-megapixel sensor? That depends on a wide number of variables like the camera lens and the software doing the image processing, but the PureView 808 provided some truly impressive performance for its time.

While smartphone cameras using this capture tech don’t typically use each pixel individually, they still have the option to. And while you could use that to create a 108-megapixel image, you can also use it to create lossless digital “zoom.” Typically, this kind of “zoom” involves basically cropping into the image—you’re using a smaller section of the sensor with fewer pixels to create a final image with the same resolution. As a result, you lose some quality.

As you digitally “zoom” with a high-resolution sensor, however, you simply ungroup the pixels. So, the 27-megapixel image will use 27 million photosites on the sensor just like it would with a regular camera, but because that only covers a smaller portion of the sensor, it will make it look as if you’ve zoomed in.

If a smartphone maker did want to enable the 108-megapixel capture, it could. Though, the huge file size and likely poor low-light performance would require specific conditions to be useful.

We’re still waiting on quite a few details about the phone in which this camera will actually show up. But, the software that goes along with this new sensor will be key in determining its performance. After all, almost every smartphone camera now takes multiple pictures every time you push the button and mashes all that image data into one final image in a fraction of a second. This “computational photography” model often provides more consistent results—especially in challenging shooting conditions—but it also means that the software and processing in the phone has a much more profound effect on the overall look.

Ultimately, however, this new sensor takes up more room inside of the smartphone and will likely require a slightly larger lens to cover it. But, as manufacturers max out the capabilities of older camera hardware, this kind of evolution may be necessary. And that may ultimately be a good thing for smartphone camera users.