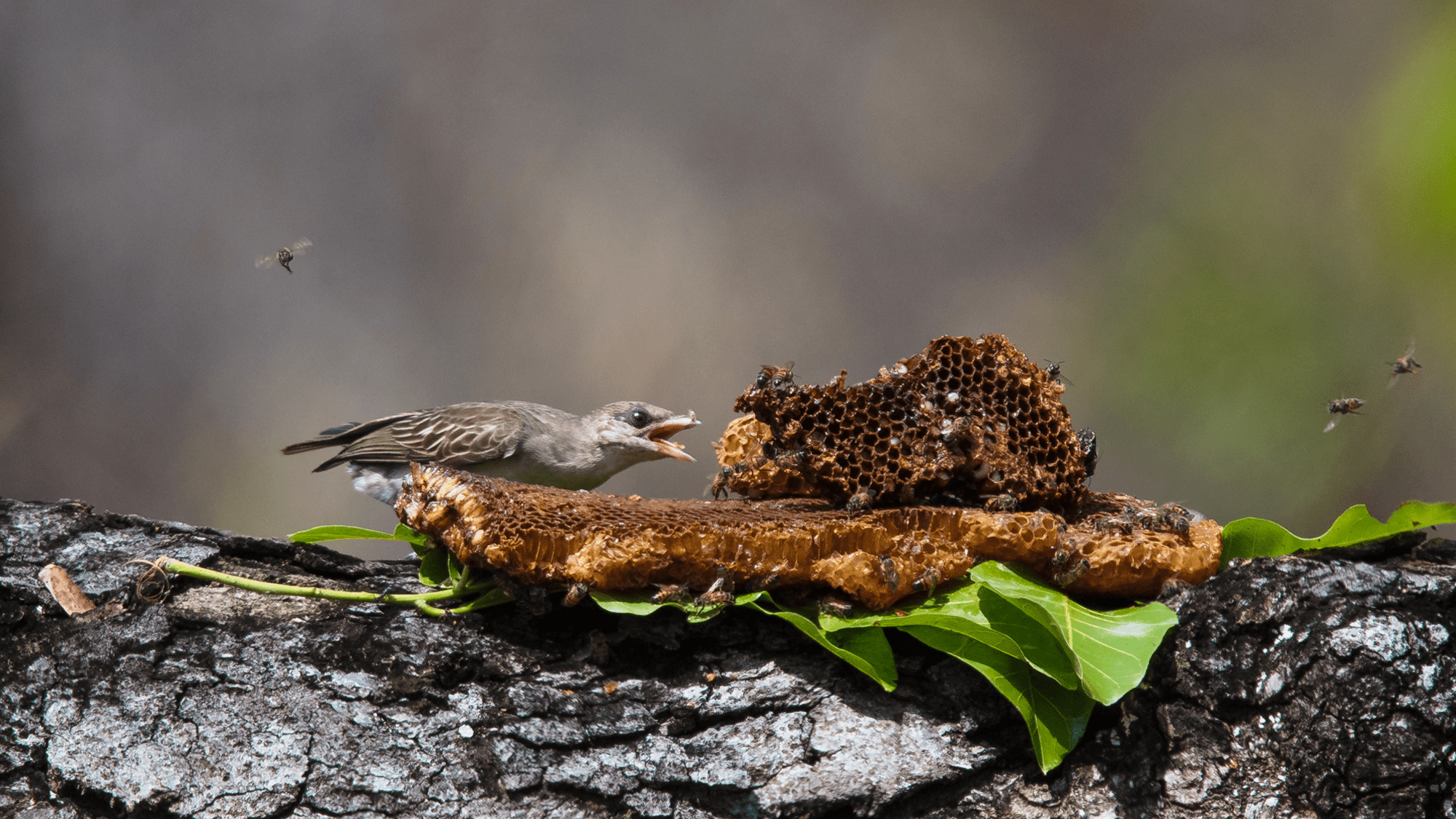

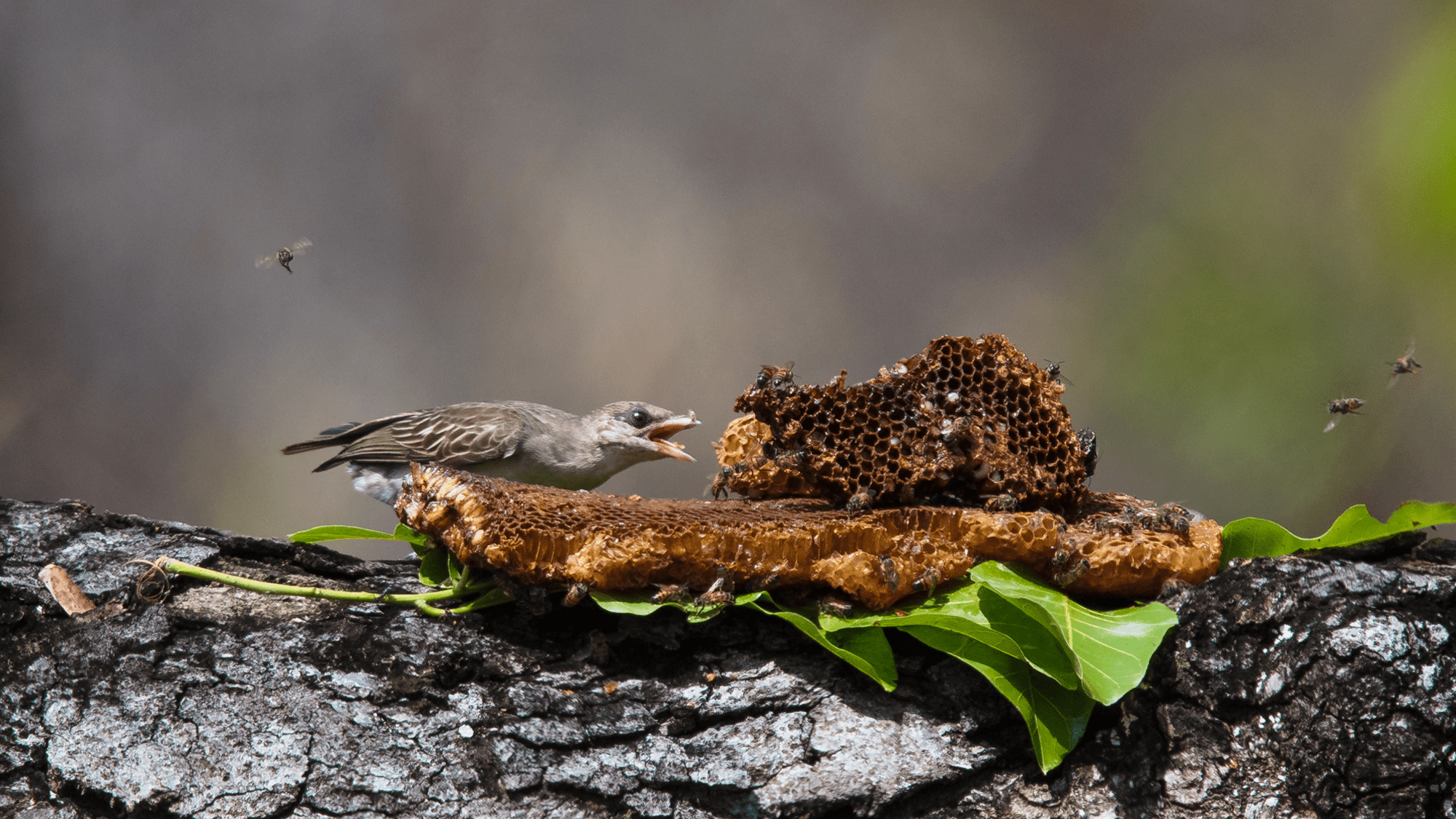

For centuries, a tale of the honeyguide bird and honey badger working together in some African countries to get into bees’ nests to get to their delicious honey and share the spoils has intrigued naturalists. Finding real evidence of this symbiotic coexistence has been tricky—until now. A study published June 29 in the Journal of Zoology used almost 400 interviews with honey-hunters across Africa to find that the birds and badgers have in fact been teaming up.

[Related: Artificial intelligence is helping scientists decode animal languages.]

“While researching honeyguides, we have been guided to bees’ nests by honeyguide birds thousands of times, but none of us have ever seen a bird and a badger interact to find honey,” study co-author and University of Cape Town behavioral ecologist Jessica van der Wal said in a statement. “It’s well-established that honeyguides lead humans to bees’ nests, but evidence for bird and badger cooperation in the literature is patchy – it tends to be old, second-hand accounts of someone saying what their friend saw. So we decided to ask the experts directly.”

Residents of the 11 communities surveyed have spent generations searching for wild honey, including with assistance of honeyguide birds. Wild honey is a high-energy food that can provide up to 20 percent of a person’s calories.

Most of the communities in the survey had doubts that honeyguide birds and honey badgers help each other get honey, and 80 percent reported never seeing the two interact.

However, responses from three communities in Tanzania stood out. Many people there reported seeing honeyguide birds and honey badgers working together to get beeswax and honey from nests. These sightings were most common amongst the Hadzabe honey-hunters, where 61 percent said they had seen the interaction.

[Related: Birds And Humans ‘Talk’ To Each Other To Outsmart Bees.]

“Hadzabe hunter-gatherers quietly move through the landscape while hunting animals with bows and arrows, so are poised to observe badgers and honeyguides interacting without disturbing them. Over half of the hunters reported witnessing these interactions, on a few rare occasions,” study co-author and University of California, Los Angeles, evolutionary anthropologist Brian Wood said in a statement.

In the study, the team built out the step-by-step process that must happen for honey badgers and honeyguide birds to work together. Some of these steps, like a bird spotting and approaching the badger, were plausible. Other situations, such as a honeyguide chirping to the badger and the badger following the bird to a bees’ nest are unclear. Badgers are known for poor hearing and bad eyesight and these sensory issues are not ideal for following a chattering bird.

According to the team, it is possible that only some populations of honey badgers in Tanzania have developed the skill sets needed to work together with honeyguide birds. Those skills are then passed among generations. Badgers and birds could also cooperate in more places, but haven’t been observed.

“The interaction is difficult to observe because of the confounding effect of human presence: observers can’t know for sure who the honeyguide bird is talking to – them or the badger,” co-author and University of Cambridge behavioral ecologist Dominic Cram said in a statement. “But we have to take these interviews at face value. Three communities report to have seen honeyguide birds and honey badgers interacting, and it’s probably no coincidence that they’re all in Tanzania.”

In future studies, the authors highlight more engagement with communities, learning from their observations, and integrating cultural and scientific knowledge to enrich and accelerate research.