The third in a series of posts about the major myths of robotics, and the role of science fiction role in creating and spreading them. Previous topics: Robots are strong, the myth of robotic hyper-competence, and robots are smart, the myth of inevitable AI.

When the world’s most celebrated living scientist announces that humanity might be doomed, you’d be a fool not to listen.

“Success in creating AI would be the biggest event in human history,” wrote Stephen Hawking in an op-ed this past May for The Independent. “Unfortunately, it might also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks.”

The Nobel-winning physicist touches briefly on those risks, such as the deployment of autonomous military killbots, and the explosive, uncontrollable arrival of hyper-intelligent AI, an event commonly referred to as the Singularity. Here’s Hawking, now thoroughly freaking out:

Hawking isn’t simply talking about the Singularity, a theory (or cool-sounding guesstimate, really) that predicts a coming era so reconfigured by AI, we can’t even pretend to understand its strange contours. Hawking is retelling an age-old science fiction creation myth. Quite possibly the smartest human on the planet is afraid of robots, because they might turn evil.

If it’s foolish to ignore Hawking’s doomsaying, it stands to reason that only a grade-A moron would flat-out challenge it. I’m prepared to be that moron. Except that it’s an argument not really worth having. You can’t disprove someone else’s version of the future, or poke holes in a phenomenon that’s so steeped in professional myth-making.

I can point out something interesting, though. Hawking didn’t write that op-ed on the occasion of some chilling new revelation in the field of robotics. He references Google’s driverless cars, and efforts to ban lethal, self-governing robots that have yet to be built, but he presents no evidence that ravenous, killer AI is upon us.

What promped his dire warning was the release of a big-budget sci-fi movie called Transcendence. It stars Johnny Depp as an AI researcher who becomes a dangerously powerful AI, because Hollywood rarely knows what else to do with sentient machines. Rejected by audiences and critics alike, the film’s only contribution to the general discussion of AI was the credulous hand-wringing that preceded its release. Transcendence is why Hawking wrote about robots annihilating the human race.

This is the power of science fiction. It can trick even geniuses into embarrassing themselves.

* * *

The slaughter is winding down. The robot revolt was carefully planned, less a rebellion than a synchronized, worldwide ambush. In the factory that built him, Radius steps onto a barricade to make it official:

A human—soon to be the last of his kind—interjects, but no one seems to notice. Radius continues.

This speech from Karel Capek’s 1920 play, R.U.R., is the nativity of the evil robot. What reads today like yet another snorting, tongue-in-cheek bit about robot uprisings comes from the work that introduced the word “robot,” as well as the concept of a robot uprising. R.U.R. is sometimes mentioned in discussions of robotics as a sort of unlikely historical footnote—isn’t it fascinating that the first story about mass-produced servants also features the inevitable genocide of their creators?

But R.U.R. is more than a curiosity. It is the Alpha and the Omega of evil robot narratives, debating every facet of the very myth its creating in its frantic, darkly comic ramblings.

The most telling scene comes just before the robots breach their defenses, when the humans holed up in the Rossum’s Universal Robots factory are trying to determine why their products staged such an unexpected revolt. Dr. Gall, one of the company’s lead scientists, blames himself for “changing their character,” and making them more like people. “They stopped being machines—do you hear me?—they became aware of their strength and now they hate us. They hate the whole of mankind,” says Gall.

There it is, the assumption that’s launched an entire subgenre of science fiction, and fueled countless ominous “what if” scenarios from futurists and, to a lesser extent, AI researchers: If machines become sentient, some or all of them will become our enemies.

But Capek has more to say on the subject. Helena, a well-meaning advocate for robotic civil rights, explains why she convinced Gall to tweak their personalities. “I was afraid of the robots,” she says.

It makes sense, doesn’t it? Humans are obviously capable of evil. So a sufficiently human-like robot must be capable of evil, too. The rest is existential chemistry. Combine the moral flaw of hatred with the flawless performance of a machine, and death results.

Karel Capek, it would seem, really knew his stuff. The playwright is even smart enough to skewer his own melodramatic talk of inevitable hatred and programmed souls, when the company’s commercial director, Busman, delivers the final word on the revolt.

Busman foretells the version of the Singularity that doesn’t dare admit its allegiance to the myth of evil robots. It’s the assumption that intelligent machines might destroy humanity through blind momentum and numbers. Capek manages to include even non-evil robots in his tale of robotic rebellion.

As an example of pioneering science fiction, R.U.R. is an absolute treasure, and deserves to be read and staged for the foreseeable future. But when it comes to the public perception of robotics, and our ability to talk about machine intelligence without sounding like children startled by our own shadows, R.U.R. is an intellectual blight. It isn’t speculative fiction, wondering at the future of robotics, a field that didn’t exist in 1920, and wouldn’t for decades to come. The play is a farcical, fire-breathing socio-political allegory, with robots standing in for the world’s downtrodden working class. Their plight is innately human, however magnified or heightened. And their corporate creators, with their ugly dismissal of robot personhood, are caricatures of capitalist avarice.

Worse still, remember Busman, the commercial director who sees the fall of man as little more than an oversupply of a great product? Here’s how he’s described, in the Dramatis Personae: “fat, bald, short-sighted Jew.” No other character gets an ethnic or cultural descriptor. Only Busman, the moneyman within the play’s cadre of heartless industrialists. This is the sort of thing that R.U.R. is about.

The sci-fi story that gave us the myth of evil robots doesn’t care about robots at all. Its most enduring trope is a failure of critical analysis, based on overly literal or willfully ignorant readings of a play about class warfare. And yet, here we are, nearly a century later, still jabbering about machine uprisings and death-by-AI, like aimless windup toys constantly bumping into the same wall.

* * *

To be fair to the chronically frightened, some evil robots aren’t part of a thinly-veiled allegory. Sometimes a Skynet is just a Skynet.

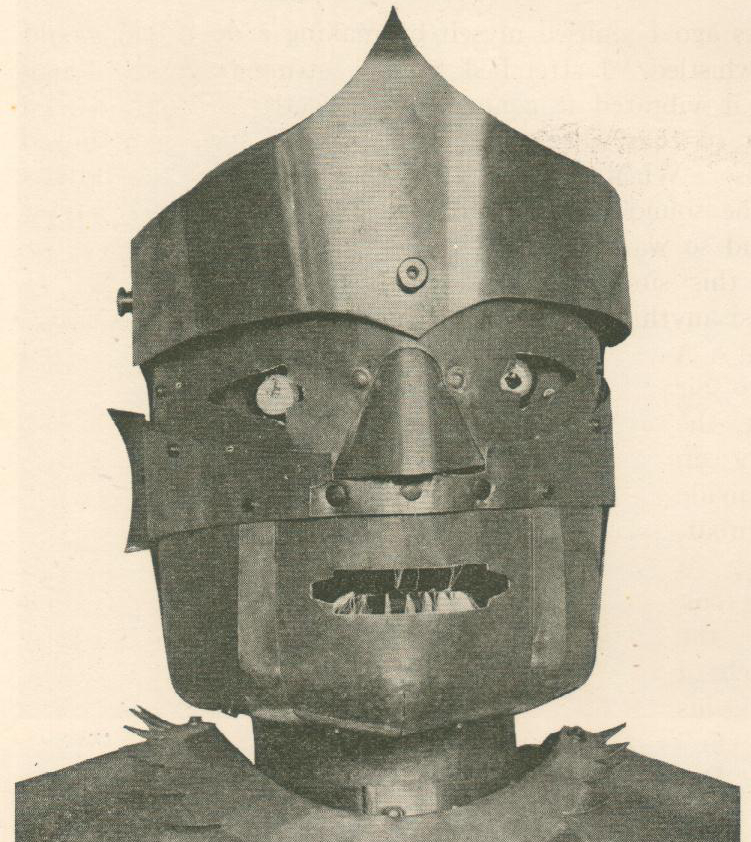

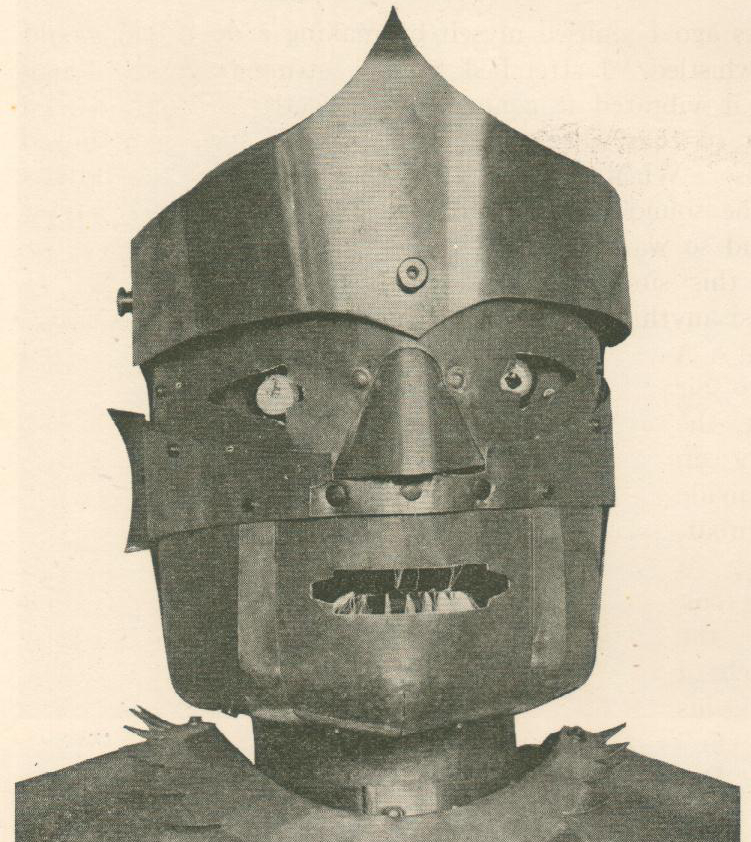

I wrote about the origins of that iconic killer AI in a previous post, but there’s no escaping the reach and influence of The Terminator. If R.U.R. laid the foundations for this myth, James Cameron’s 1984 film built a towering monument in its honor. The movie spawned three sequels and counting, as well as a TV show. And despite numerous robot uprisings on the big and small screen in the 30 years since the original movie hit theaters, Hollywood has yet to top the opening sequence’s gut-punch visuals (see above).

Here’s how Kyle Reese, a veteran of the movie’s desperate machine war, explains the defense network’s transition from sentience to mass murder: “They say it got smart, a new order of intelligence. Then it saw all people as a threat, not just the ones on the other side. Decided our fate in a microsecond: extermination.”

The parable of Skynet has an air of feasibility, because its villain is so dispassionate. The system is afraid. The system strikes out. There’s no malice in its secret, instantiated heart. There’s only fear, a core component of self-awareness, as well as the same, convenient lack of empathy that allows humans to decimate the non-human species that threaten our survival. Skynet swats us like so many plague-carrying rats and mosquitos.

Let’s not be coy, though: Skynet is not a realistic AI, or one based on realistic principles. And why should it be? It’s the monster hiding under your bed, with as many rows of teeth and baleful red eyes as it needs to properly rob you of sleep. This style and degree of evil robot is completely imaginary. Nothing has ever been developed that resembles the defense network’s cognitive ability or limitless skill set. Even if it becomes possible to create such a versatile system, why would you turn a program intended to quickly fire off a bunch of nukes into something approaching a human mind?

“People think AI is much broader than it is,” says Daniel H. Wilson, a roboticist and author of the New York Times bestselling novel, Robopocalypse. “Typically an AI has a very limited set inputs and outputs. Maybe it only listens to information from the IMU [inertial measurement unit] of a car, so it knows when to apply the brakes in an emergency. That’s an AI. The idea of an AI that solves the natural language problem—a walking, talking, ‘I can’t do that, Dave,’ system—is very fanciful. Those sorts of AI are overkill for any problem.” Only in science fiction does an immensely complex and ambitious Pentagon project over-perform, beyond the wildest expectations of its designers.

In the case of Skynet, and similar fantasies of killer AI, the intent or skill of the evil robot’s designers is often considered irrelevant—machine intelligence bootstraps itself into being by suddenly absorbing all available data, or merging multiple systems into a unified consciousness. This sounds logical, until you realize that AIs don’t inherently play well together.

“When we talk about how smart a machine is, it’s really easy for humans to anthropomorphize, and think of it in the wrong way,” says Wilson. “AI’s do not form a natural class. They don’t have to be built on the same architecture. They don’t run the same algorithms. They don’t experience the world in the same way. And they aren’t designed to solve the same problems.”

In his new novel, Robogenesis (which comes out June 10th), Wilson explores the notion of advanced machines that are anything but monolithic or hive-minded. “In Robogenesis, the world is home to many different AIs that were designed for different tasks and by different people, with varying degrees of interest in humans,” says Wilson. “And they represent varying degrees of danger to humanity.” It goes without saying that Wilson is happily capitalizing on the myth of the evil robot—Robopocalypse, which was optioned by Stephen Spielberg, features a relatively classic super-intelligent AI villain called Archos. But, as with The Terminator, this is fiction. This is fun. Archos has a more complicated and defensible set of motives, but no new evil robot can touch Skynet’s legacy.

And Skynet isn’t an isolated myth of automated violence, but rather a collection of multiple, interlocking sci-fi myths about robots. It’s hyper-competent, executing a wildly complex mission of destruction—including the resource collection and management that goes into mass-producing automated infantry, saboteurs, and air power. And Skynet is self-aware, because SF has prophesied that machines are destined to become sentient. It’s fantasy based on past fantasy, and it’s hugely entertaining.

I’m not suggesting that Hollywood should be peer-reviewed. But fictional killer robots live in a kind of rhetorical limbo, that clouds our ability to understand the risks associated with non-fictional, potentially lethal robots. Imagine an article about threats to British national security mentioning that, if things really get bad, maybe King Arthur will awake from his eons-long mystical slumber to protect that green and pleasant land. Why would that be any less ridiculous than the countless and constant references to Skynet, a not-real AI that’s more supernatural than supercomputer? Drone strikes and automated stock market fluctuations have as much to do with Skynet as with Sauron, the necromancer king from The Lord of the Rings.

So when you name-drop the Terminator‘s central plot device as a prepackaged point about the pitfalls of automation, realize what you’re actually doing. You’re talking about an evil demon summoned into a false reality. Or, the case of Stephen Hawking’s op-ed, realize what you’re actually reading. It looks like an oddly abbreviated warning about an extinction-level threat. In actuality, it’s about how science fiction has super neat ideas, and you should probably check out this movie starring Johnny Depp, because maybe that’s how robots will destroy each and every one of us.