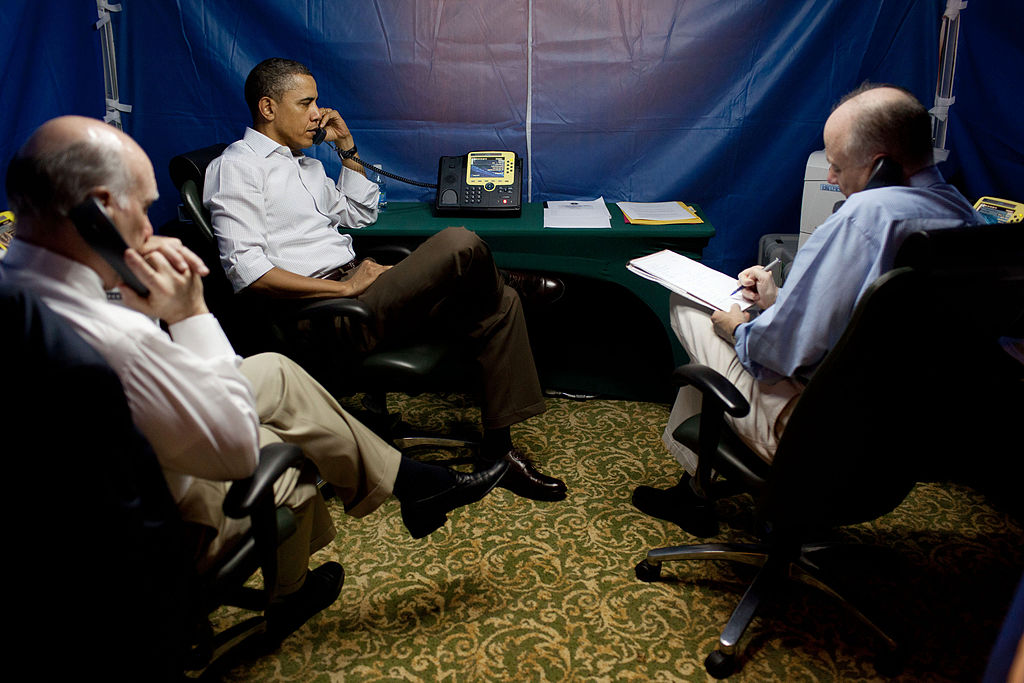

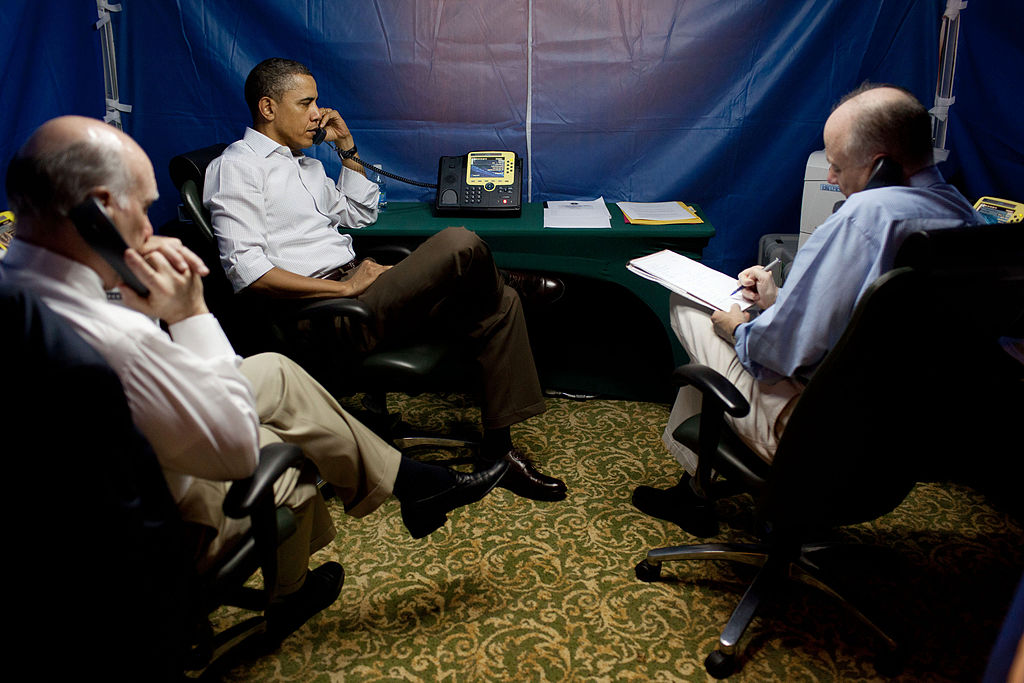

When members of the U.S. military and other federal government agencies need to discuss the big secrets, they go into secure, soundproof rooms called “Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities,” or SCIFs (pronounced “skiffs”). Except, according to initial research by acoustics engineer Marlund Hale, the rooms might not be all that soundproof.

The door and frame systems often don’t seal well, letting noise escape

The problem, Hale says, is that the whole of a SCIF is less secure than the sum of its parts. The requirements for making a site secure are elaborate; the unclassified version of the technical specifications runs at 158 pages. Acoustic insulation standards cover all sides of the room, including the floor and ceiling. Despite these standards for individual sections, the door and frame systems often don’t seal as well as intended, letting noise escape, Hale says. He suggests the flaws arise when contractors neglect specific design details during construction. As a result, SCIFs are no more soundproof than a typical California apartment, according to Hale, who presented his findings yesterday at a meeting of the Acoustical Society of America.

Current Department of Defense design standards “only require sufficient acoustical isolation to prevent a casual passerby from understanding classified information, but do not need to be adequate to prevent a deliberate effort by someone to understand that information,” Hale says.

Next week, Hale will conduct 13 more tests on another military installation. Among his early recommendations are special airlock-like, two-part entrances, which would prevent sound from traveling down the hall when a door opens. Until new improvements are adopted for acoustic insulation, it’s probably a good idea for people with secret information to use their inside voices when inside a SCIF.