Man Taking HIV-Prevention Drug Tests Positive For HIV

What does it mean?

A man was recently diagnosed with HIV after 24 months on a drug intended to prevent HIV infection. A physician at the Maple Leaf Medical Clinic in Toronto, Canada who treated the patient presented the case study last week at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Boston. Here’s what happened, and why it matters.

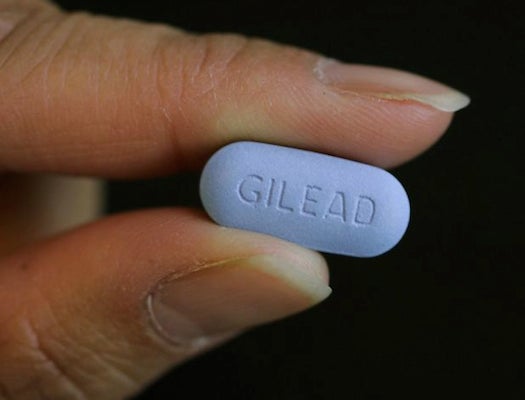

What is the drug? Its brand name is Truvada, otherwise known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The FDA approved it in 2012 as part of safe sex practices to prevent HIV. Truvada combines two different drugs called Emtriva and Viread that, together, block an enzyme that the virus uses to copy its own DNA. Without this enzyme, HIV can’t replicate inside the body, so the drug prevents the virus from spreading.

Who is this patient? The patient is a 43-year-old Canadian man who has sex with men. His self-reports and pharmacy records show that he took PrEP regularly enough to ensure more than 90 percent efficacy (estimates vary, but most say the patient would need to take the drug at least four times per week for it to be 92 to 99 percent effective).

What’s his diagnosis? The patient’s blood had the p24 antigen, which shows up in the system about three weeks after HIV infection but disappears shortly thereafter, according to Poz. The patient told his doctors that he had unprotected sex several times a few weeks before he tested positive and doesn’t use intravenous drugs. He was diagnosed with a rare strain of HIV that is resistant to both drugs in Truvada, as Fusion reports.

How did HIV sneak past the drug? Doctors aren’t totally sure. But it seems that the patient contracted the resistant virus from one other person, which shows that the virus didn’t evolve resistance in his body. Overall it seems like a case of bad luck—the patient was exposed to a particularly virulent strain of HIV in an instance in which he didn’t use other means of protecting himself against HIV.

What does it mean for others taking the drug? It doesn’t mean that the drug doesn’t work, as Gawker points out. It just means that it’s not 100 percent effective, which is perhaps disappointing but not surprising (doctors know better than to ever say that a treatment or prevention is totally foolproof). Treatments like these are still important tools to fight the spread of HIV, especially since one in six gay men is expected to contract the virus, according to a recent report from the CDC (in gay black men, that number is one in two). In the short-term, this case study is a reminder to those taking Truvada that it should be used with other prevention strategies, like with condoms. In the longer term, researchers will need to perform more trials to better understand the factors that can alter Truvada’s efficacy.