Archaeologists have spent years puzzling over evidence of severed head rituals among Iron Age communities in the northeast Iberian Peninsula. Multiple groups of the Indigetes and Laietani peoples from present-day Spain and Portugal practiced these violent public displays at least as far back as the first millennium BCE. And sometimes, they did so with elaborate preparation techniques such as driving iron nails through the skulls.

While researchers previously believed the techniques were restricted to an area north of Catalonia’s Llobregat River, recently examined cranial remains tell a different story. According to a study published in the journal Trabajos de Prehistoria, at least two other Iberian groups further south—the Cessetani and the Ilergetes—observed severed head rituals as early as the 6th century BCE.

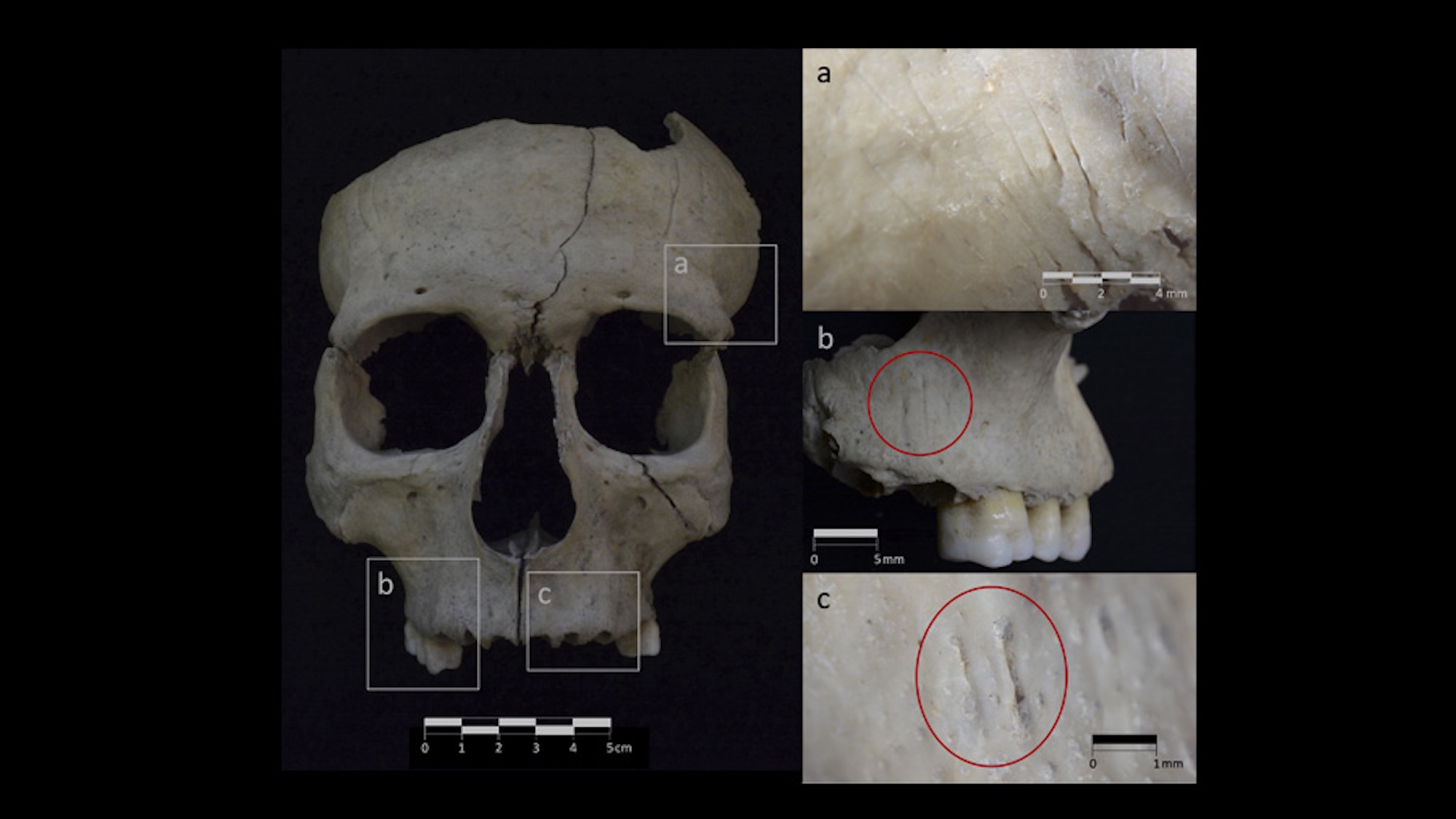

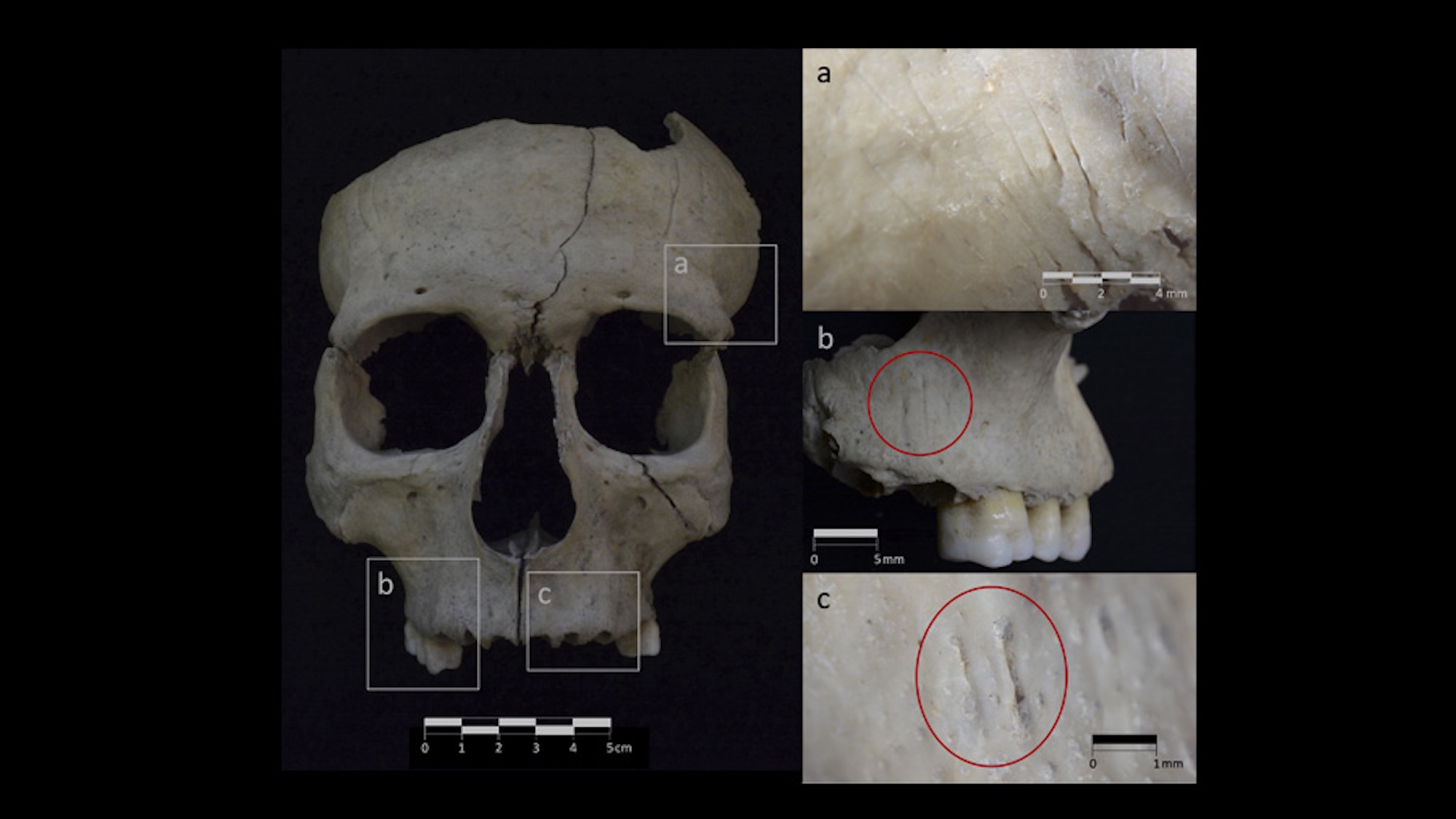

“Bioanthropological and waste analyses have allowed us to identify injuries produced with sharp objects at a time close to death. Due to their arrangement, depth and location, they are compatible with the ritual of severed heads,” said Rubén de la Fuente, a study co-author and archaeologist at Spain’s Autonomous University of Barcelona.

De la Fuente and his collaborators analyzed five cranial remains excavated near the municipality of Olèrdola about 25 miles west of Barcelona, as well as 10 previously collected samples from the city of Molí d’Espígol another 60 miles north. In addition to the injury marks, the team confirmed natural materials used for preservation and display. These ranged from vegetable and animal fats, to pine resins, waxes, and oils.

“These are results that force us to rethink the cultural framework of the ritual, which until now was considered to be specific only to the peoples north of the Llobregat River, and point to a wider territorial dispersion than we thought,” added Catalan Institute of Classical Archaeology researcher and study co-author Eulàlia Subirà.

At Olèrdola, the skull fragments all belonged to a single male between eight and 15-years-old. Three separate people are linked to the bones recovered from Molí d’Espígol, one of whom was a similarly aged male. On the Olèrdola skull, researchers also noted markings made on the jawbone using needle-like tools similar to those found at other Iberian locations.

“These marks were made to remove the flesh from the skull and indicate that, in addition to the scalp, the skin of the individual’s face was also removed,” said Subirà. “It is an infrequent practice, but it is documented in the ritual in European sites in France and the United Kingdom.”

At both sites, the cranial fragments were all discovered in what were common or public spaces, implying the severed heads possessed symbolic or performative importance. At Olèrdola, the skull was placed on a ground floor in one of the settlement’s entrance wall towers. According to De la Fuente, the Molí d’Espígol bones were housed inside a space of “indeterminate use, but architecturally unique enough to be a prominent or emblematic place of the settlement.”

It’s still unclear who these individuals were in relation to their decapitators, but De la Fuente’s team has their theories. Cremation was the primary burial practice throughout the Iberian region, meaning the careful preparation of severed heads was likely reserved for captured enemies. Because similar rituals were practiced by Gallic peoples of present-day France, there is now a growing body of evidence that indicates a potential cultural link between the Celtic and Gallic worlds.