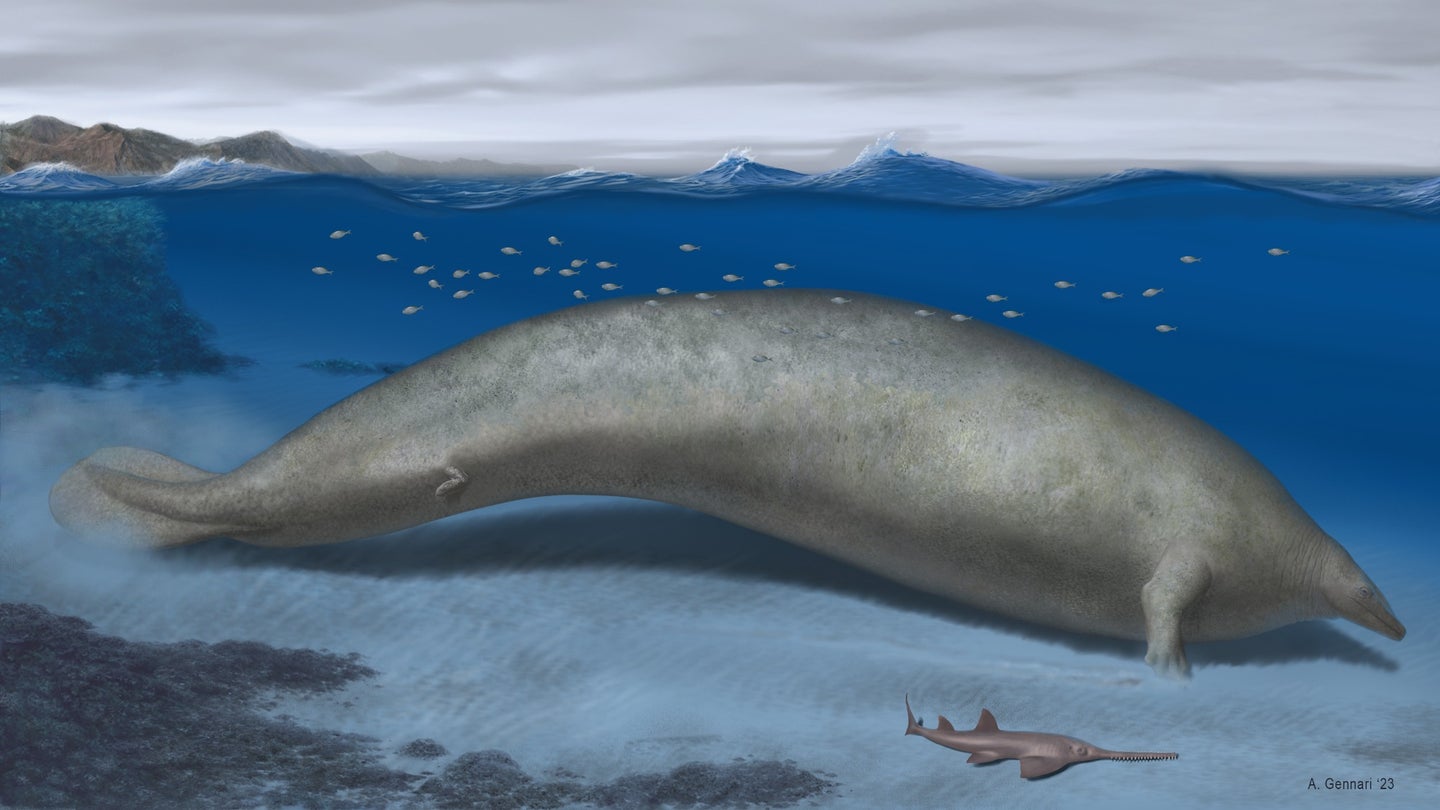

This giant sea cow-like whale may have been the heaviest creature to ever live on Earth

Millions of years ago, the stubby-armed, 750,000-pound Perucetus colossus chilled out in the ocean shallows.

It’s hard to deny that whales are some of the most charismatic megafauna on our planet. The blue whale, specifically, with its massive size, friendly demeanor, and devastating backstory is one that has captured imaginations for decades. But there may be a new contender for the largest animal to live on earth—or at least there was one around 40 million years ago.

An international team of scientists recently uncovered some giant bones in a fossil-filled coastal desert Peru, namely 13 vertebrae, four ribs and a hip bone. These fossils lead them to a discovery of a sea-dwelling mammal that would’ve weighed up to 340 metric tons. Blue whales have gotten to around 190 metric tons at their heaviest, and the most massive dinosaur, the supersized sauropod Argentinosaurus, was estimated to weigh around 76 tons.

[Related: Millions of years ago, marine reptiles may have used Nevada as a birthing ground.]

Despite their incredible size, the newly-named Perucetus colossus was likely not a fighter, similar to some of the world’s other favorite sea mammals.

“Because of its heavy skeleton and, most likely, its very voluminous body, this animal was certainly a slow swimmer. This appears to me, at this stage of our knowledge, as a kind of peaceful giant, a bit like a super-sized manatee. It must have been a very impressive animal, but maybe not so scary,” paleontologist Olivier Lambert of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels told Reuters. Lambert and his colleagues published their findings August 2 in Nature.

The chilled-out attitude of the Perucetus was likely not the only thing they had in common with today’s manatees. Its dense, vast skeleton was even estimated to be twice as heavy as a blue whale’s at 5 to 8 tons, even though length-wise, the blue whale still had them beat.

“It took several men to shift them [the fossils] into the middle of the floor in the museum for me to do some 3D scanning,” author Rebecca Bennion from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels told the BBC. “The team that drilled into the center of some of these vertebrae to work out the bone density—the bone was so dense, it broke the drill on the first attempt.”

This characteristic doesn’t exist in today’s cetaceans (the family including whales, dolphins and porpoises), but it does appear in sirenians. One author especially noted the Steller’s sea cow, which was discovered in the 1700s only to go extinct within three decades of its discovery due to overhunting.

[Related: These now-extinct whales were kind of like manatees.]

Like manatees, the Perucetus also appears to have had front limbs. Strangely enough, the animal also possessed vestigial back limbs, a possible evolutionary hangover from when whales evolved from land-based, dog-sized mammals 50 million years ago.

One looming question about the Perucetus is how it ate—the researchers unfortunately didn’t find it’s skull, so the authors have multiple hypotheses: it may have scavenged, ate sea grass, or even scooped up shellfish and worms from the mud floor like today’s gray whales.

Nevertheless, just finding a creature that could’ve been this size opens a whole new can of worms for paleontologists to uncover.

“The extreme skeletal mass of Perucetus suggests that evolution can generate organisms with characteristics that go beyond our imagination,” study author and Italian paleontologist Giovanni Bianucci told CNN. And that is a massive deal.