Most experts believe complex life on Earth can be traced back roughly 635-to-800 million years ago to the Cambrian Period—but some researchers say they now possess evidence that dramatically rewrites the evolutionary narrative. According to an international group led by Cardiff University’s Ernest Chi Fru, the planet’s very first (yet ultimately unsuccessful) simple single-celled organisms arrived 2.1 billion years ago, a full 1.5 billion years earlier than the current prevailing theory. Unsurprisingly, however, such a major assertion is already being met by skeptics.

Evidence of the planet’s first microbial life is dated 3.7 billion years ago, but it took at least another 1.3 billion years for oxygen-based cyanobacteria to arrive. Current fossil records indicate some of the earliest forms of animal life, like sea sponges, showed up around 800 million years ago. Meanwhile, researchers understand the Cambrian Period’s increase in marine phosphorus and seawater oxygen levels 635 million years ago spurred the evolutionary track leading to today’s biodiversity. But Chi Fru’s team now argues that at least one other attempt at life occurred in the distant past. The theory, presented in a study published July 25 in the journal Precambrian Research, points to alleged fossils and rock formations located in present-day Gabon as proof.

“The availability of phosphorus in the environment is thought to be a key component in the evolution of life on Earth, especially in the transition from simple single cell organisms to complex organisms like animals and plants,” Chi Fru said in an accompanying statement on July 29.

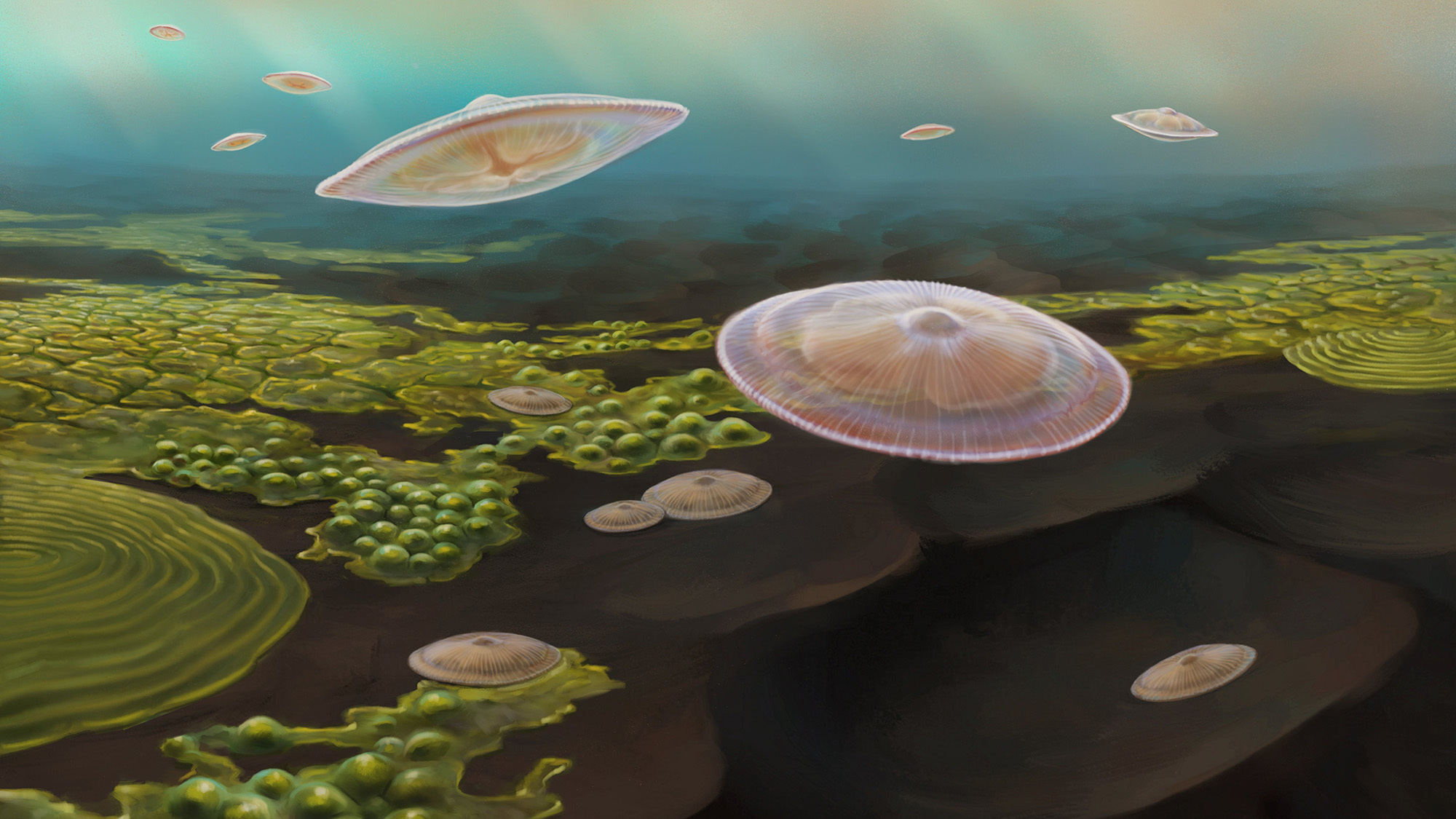

According to Chi Fru, these necessary phosphorus and oxygen levels arose from rare underwater volcanic activity that followed the collision and suturing of the Congo and São Francisco cratons into a single body. A subsequently created, shallow inland sea then provided a nutrient-rich testing environment for the earliest trials in complex biological evolution.

“This created a localized environment where cyanobacterial photosynthesis was abundant for an extended period of time, leading to the oxygenation of local seawater and the generation of a large food resource,” Chi Fru argued. “This would have provided sufficient energy to promote an increase in body size and greater complex behavior observed in primitive simple animal-like life forms such as those found in the fossils from this period.”

[Related: All living birds share an ‘iridescent’ ancestor.]

But don’t expect complexity from the two-billion-year-old deep sea evolutionary experiments—according to the team, these life forms resembled slimy, single-cell mold cultures that reproduced with spores. And while these brainless organisms were allegedly capable of small movements, in the end the inland water body’s isolation and resultant nutrient deficiency ensured the proto-slime’s eventual extinction.

Such a bold claim is not without its skeptics. As the BBC noted on July 28, many experts don’t think the alleged “fossils” cited by Chi Fru’s team are actually fossils at all, but simply masses of (albeit still-unexplained) geological formations. Others, meanwhile, aren’t opposed to the possibility that instances of higher nutrient levels occasionally occurred as far back as 2.1 billion years ago, but remain unconvinced it was enough to begin complex life.

Either way, critics say much more evidence will be needed before they shift their evolutionary timelines back 1.5 billion years.