Using Light to Target and Kill Cancer Cells, Without Chemotherapy’s Side Effects

A new, finely tuned light-based treatment kills cancer cells in mice without harming the tissue around them, and could conceivably...

A new, finely tuned light-based treatment kills cancer cells in mice without harming the tissue around them, and could conceivably used to treat a wide range of human cancers, researchers say. The therapy is much more precise than other light-therapy methods attempted to date, and it has the potential to replace chemotherapy and radiation.

Researchers at the National Cancer Institute coupled cancer-specific antibodies with a heat-sensitive dye that damages cells when exposed to specific wavelengths of light. The antibodies recognize proteins on the exterior of cancer cells, so they would easily and accurately seek out their quarry, leaving healthy cells alone. Once bound to the cancer, the antibodies’ piggyback heat-sensitive molecule could be activated to do its job.

Led by Hisataka Kobayashi, researchers worked with several photosensitizers (light-activated molecules) before settling on one called IR700. It activates in near-infrared light and has the added bonus of fluorescence, so the researchers could easily watch its progress. They attached it to three cancer antibodies that bind to three different proteins: HER2, which is over-expressed by some breast cancers; EGFR, which is over-expressed by some lung, pancreatic, and colon cancers; and PSMA, which is over-expressed by prostate cancers.

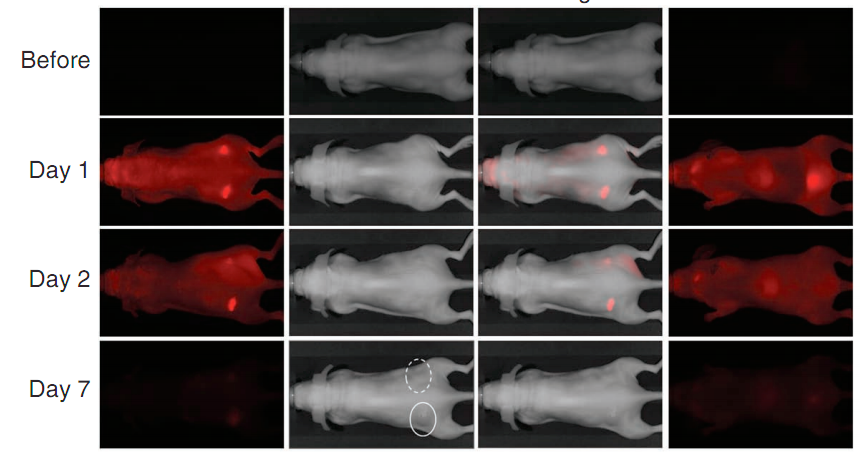

Working with mice that had been implanted with tumors, the researchers say the cancer cells bound to the protein antibodies, and when they were exposed to infrared light, the cells died. Even a single dose of IR light made a significant difference, as the image at the top shows. Infrared light has the added benefit of penetrating several centimeters into tissue, much deeper than other wavelengths, the researchers say.

One key thing about this therapy is its selectivity, the researchers say. While other light-therapy methods can damage healthy tissue, just like radiation and chemotherapy can, this method only targets cells that are over-expressing proteins associated with certain types of cancer.

Much more work needs to be done to verify that this can work in humans — for instance, the breast cancer protein used in this study is only present in less than half of breast cancers — but the team says their method shows promise. The work was published online Sunday in Nature Medicine.