Nearly a century ago, archaeologists excavating a cemetery in Upper Egypt dating back to the late 4th millennium BCE discovered a small, unrecognizable artifact in the grave of an adult male. While experts confidently dated the item back to the Predynastic era, the roughly 2.5-inch-long object’s purpose was less clear. Researchers at the University of Cambridge eventually catalogued it as “a little awl of copper, with some leather thong wound round it,” and stored it in the institution’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

However, careful reexaminations indicate the “little awl” is far more significant than originally believed—so much so that it may rewrite ancient Egyptian history. In a study published in the journal Egypt and the Levant, a team led by Newcastle University archaeologist Martin Odler argues the item is actually the region’s earliest known example of a bow drill. If true, this pushes the tool’s creation back by over 2,000 years.

“The ancient Egyptians are famous for stone temples, painted tombs, and dazzling jewelry, but behind those achievements lay practical, everyday technologies that rarely survive in the archaeological record,” Odler explained in an accompanying statement. “One of the most important was the drill: a tool used to pierce wood, stone, and beads, enabling everything from furniture-making to ornament production.”

Odler and his colleagues contend the residual leather strap is all that remains of a bowstring, which a handler would spin by pulling back-and-forth on a bow. After analyzing the tool’s overall condition, the team also believes that the relic displays damage consistent with regular use—rounded edges, a subtle curve at the working end, and light scratch marks.

Its physical condition also suggests that it was a bow drill. X-ray fluorescence scans revealed the drill was manufactured using a strange copper alloy.

“The drill contains arsenic and nickel, with notable amounts of lead and silver. Such a recipe would have produced a harder, and visually distinctive, metal compared with standard copper,” said study co-author and archaeometallurgist Jiří Kmošek. He added that the lead and silver, “may hint at deliberate alloying choices and, potentially, wider networks of materials or know-how linking Egypt to the broader ancient Eastern Mediterranean in the fourth millennium BCE.”

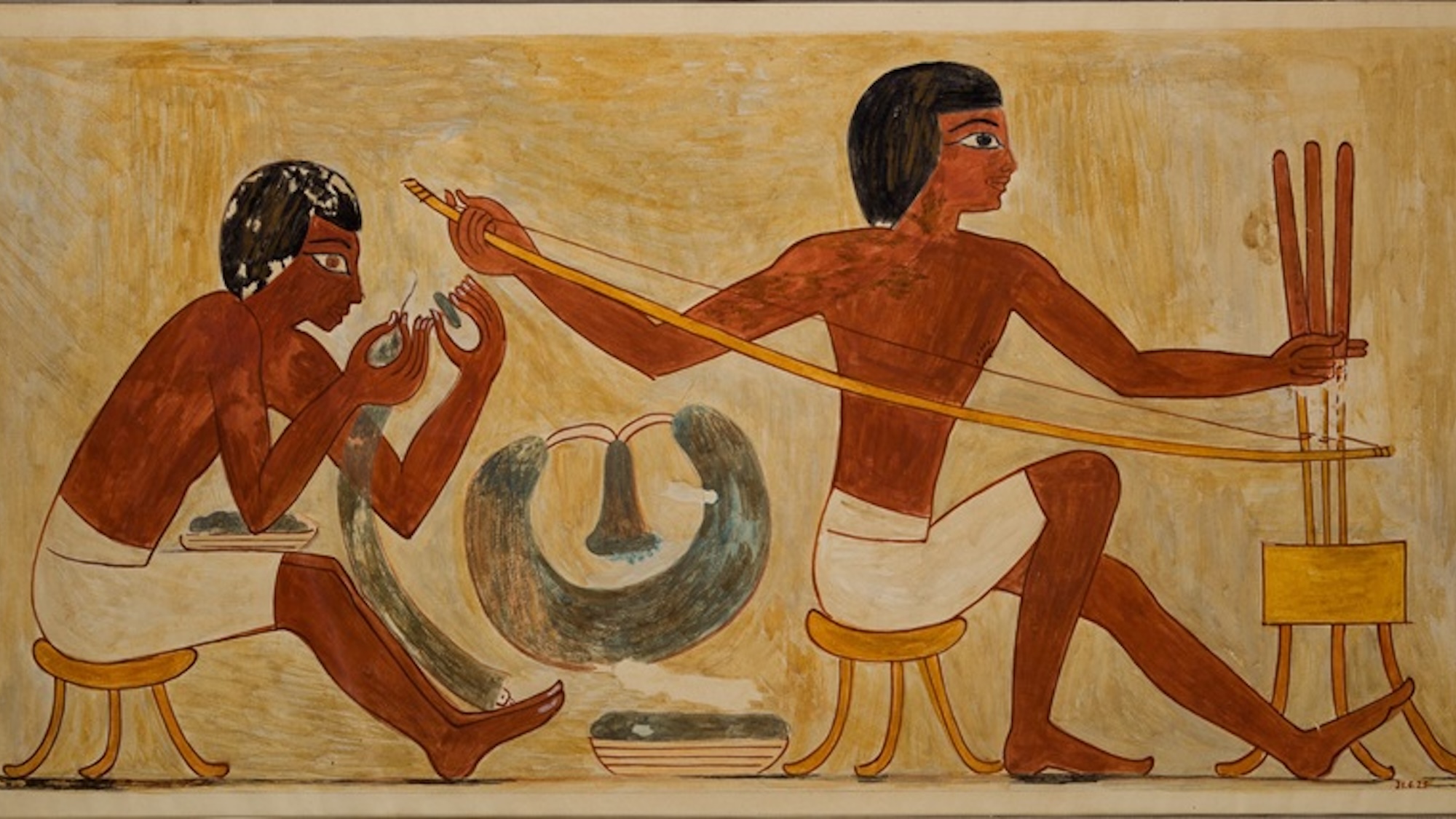

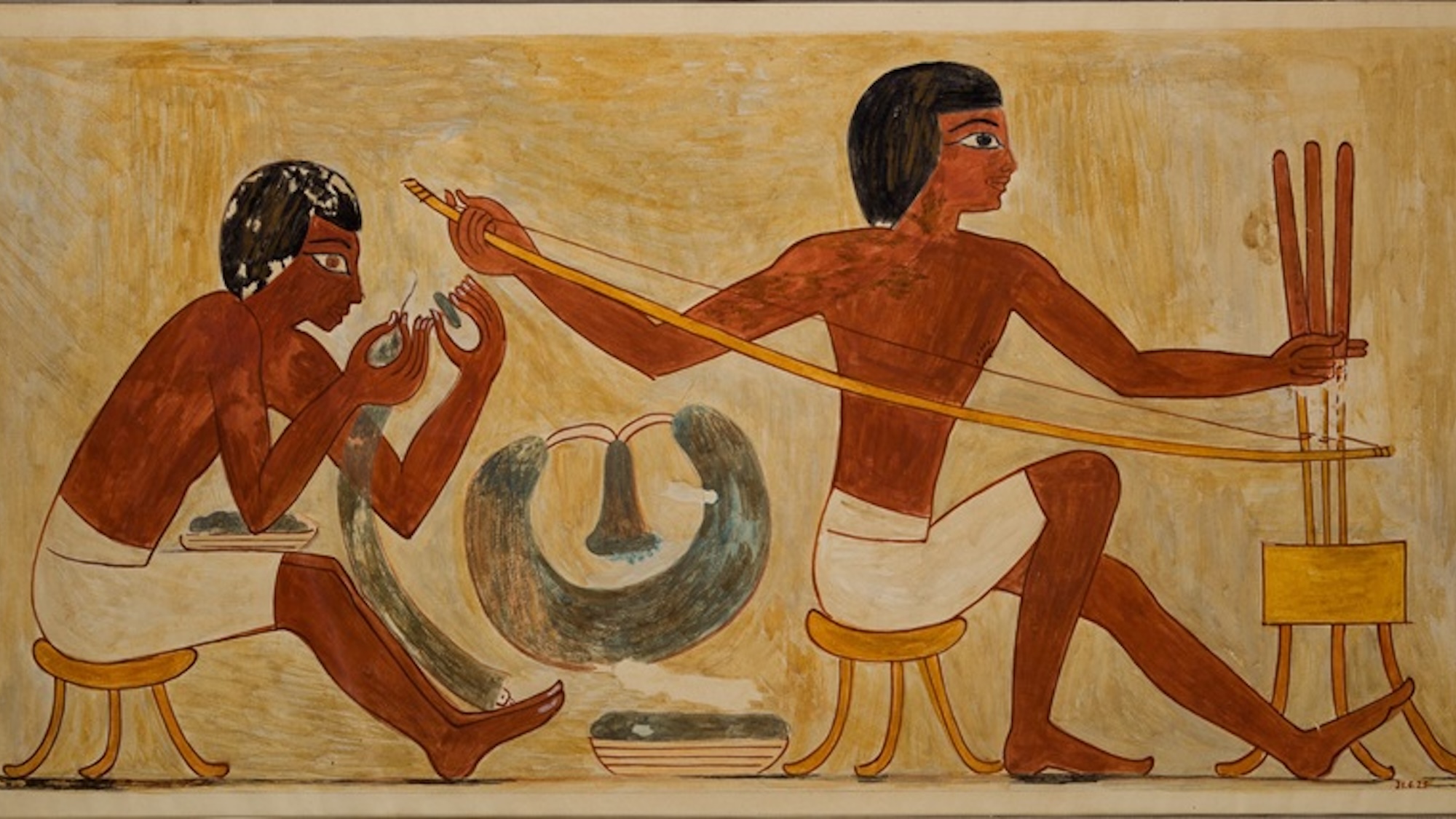

Prior to the recent reappraisal, bow drills were only documented during later eras of Egyptian history like the New Kingdom during the mid-to-late second century BCE. Evidence includes tomb artwork in the West Bank of Luxor illustrating artisans fashioning beads and woodwork.

“This re-analysis has provided strong evidence that this object was used as a bow drill—which would have produced a faster, more controlled drilling action than simply pushing or twisting an awl-like tool by hand,” added Odler. “This suggests that Egyptian craftspeople mastered reliable rotary drilling more than two millennia before some of the best-preserved drill sets.”