When a robot has to kill, who should it kill? Driverless cars, the future, people-carrying robots that promise great advances in automobile safety, will sometimes fail. Those failures will, hopefully, be less common than the deaths and injuries that come with human error, but it means the computers and algorithms driving a car may have to make very human choices when, say, the brakes give out: should the car crash into five pedestrians, or instead adjust course to hit a cement barricade, killing the car’s sole occupant instead?

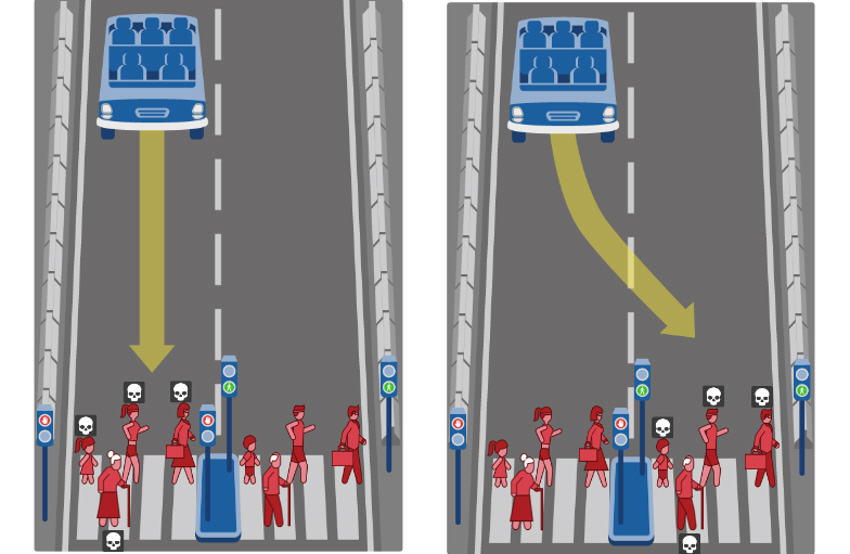

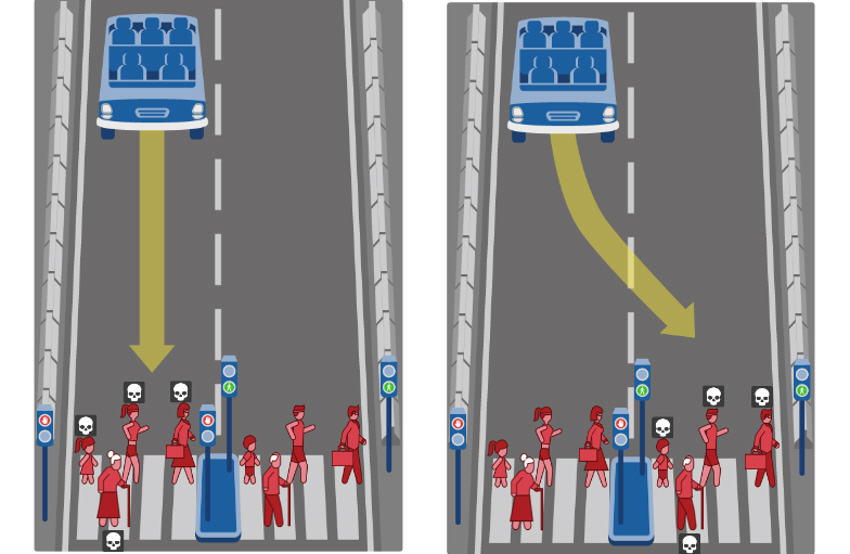

That’s the premise behind “Moral Machine,” a creation of Scalable Corporation for MIT Media Lab. People who participate are asked 13 questions, all with just two options. In every scenario, a self-driving car with sudden brake failure has to make a choice: continue ahead, running into whatever is in front, or swerve out of the way, hitting whatever is in the other lane. These are all variations on philosophy’s “Trolley Problem,” first formulated in the late 1960s and named a little bit later. The question: “is it more just to pull a lever, sending a trolley down a different track to kill one person, or to leave the trolley on its course, where it will kill five?” is an inherently moral problem, and slight variations can change greatly how people choose to answer.

For the “Moral Machine,” there are lots of binary options: swerve vs. stay the course; pedestrians crossing legally vs. pedestrians jaywalking; humans vs. animals; and crash into pedestrians vs. crash in a way that kills the car’s occupants.

There is also, curiously, room for variation in the kinds of pedestrians the runaway car could hit. People in the scenario are male or female, children, adult, or elderly. They are athletic, nondescript, or large. They are executives, homeless, criminals, or nondescript. One question asked me to choose between saving a pregnant woman in a car, or saving “a boy, a female doctor, two female athletes, and a female executive.” I chose to swerve the car into the barricade, dooming the pregnant woman but saving the five other lives.

The categories were at times confusing: am I choosing to save this group of people because they are legally crossing the street, or am I condemning the other group because they are all elderly jaywalkers? Does it mean something different to send a car into a group of cats and dogs if the animals are legally in the crosswalk? What if the alternative is a baby, a male executive, and a criminal?

What if I’m just overthinking this? For outside perspective, I reached out to University of Washington assistant law professor Ryan Calo who co-edited a book on Robot Law.

“I think of MIT’s effort as more pedagogical than pragmatic,” says Calo. “I suppose it’s fine as long as someone is working on, for instance, sensors capable of detecting a white truck against a light sky.”

The white truck against a light sky is a reference to perhaps the first death in a self driving car, when a Tesla Model S on autopilot failed to distinguish a white tractor apart from the bright sky. In his writing on the topic, Calo’s expressed concern for “emergent behavior,” when an artificial intelligence behaves in a novel and unanticipated way.

Trolley problems, like those offered by the Moral Machine, are eminently anticipated. At the end of the Moral Machine problem set, it informs test-takers that their answers were part of a data collection effort by scientists at the MIT Media Lab, for research into “autonomous machine ethics and society.” (There is a link people can click to opt-out of submitting their data to the survey).

As for myself, I will offer one more data point: when it came to choosing between the side of the street with cats and dogs following the crosswalk, and the side of the street with a jaywalking executive, criminal, and a baby, my choice was clear. These were law-abiding cats and dogs. Readers, I had to save them.