In the summer of 1967, a group of intelligence analysts gathered in the Defense Intelligence Agency’s “Green Room,” just outside of Washington, D.C., to puzzle over a strange spy satellite image. It showed a gigantic machine, something bigger than any known airplane, with wings that looked too short to fly, sitting in a fenced enclosure at Kaspisk, a small city by the Caspian Sea. “Jeez, that’s a monster,” said an Army colonel. “Yeah,” said another, “the Loch Ness Monster.” Someone added: “No, the Caspian. It’s the Caspian Monster.”

But what was it? How did it work? What did the Russians plan to do with it? The answers came slowly over the next decade: It was an ekranoplan, a new type of aircraft that exploited an aerodynamic phenomenon called ground effect to haul enormous payloads at high speeds over water. It was invented by Rostislav Alexeyev, a friend of Soviet Premier Nikita Krushchev. It was not yet working very well. And if the Amerikanski spies could think of a practical use for it, the Soviet military would have appreciated their advice, because Moscow politicians, keen to find a need for a project that owed its existence as much to connections as to any operational requirement, were hell-bent on ramming it down the armed services’ throats.

After the Cold War ended, I asked a Russian aerospace engineer what he thought of the Monster and its descendants, which were being examined intensely by the Pentagon at the time. “A waste of money,” he grumbled. “Every time it didn’t work, (the designers told Moscow) it would work if it was bigger. And they got the money for it.”

But they may have been on the right track. Today, engineers at Boeing are designing a cargo plane that, like the Caspian Monster, is designed to skim just above the water like a large sea bird. It’s dubbed the Pelican, because it will use the same “wing-in-ground effect,” or WIG, that the awkward bird does to glide almost effortlessly above the water. When applied to man-made flying vehicles, WIG aerodynamics represent a critical exception to a long-held rule of aviation-altitude equals efficiency. The reason most long-range airplanes are high-altitude jets is that flying in thick air at lower altitudes normally takes significantly more fuel. But if you get extremely close to the surface-around 50 feet or below, as a WIG vehicle would-a cushion of air generated by the plane’s velocity helps support it in flight, so that the plane cruises even more efficiently than a high-altitude jet. The WIG aircraft Boeing is developing is bigger than the Caspian Monster: Its wingspan is about the width of the front of the Capitol. Boeing engineers are counting on the notion that enormous wings will provide more opportunity for the air below them to gently lift and propel the vehicle, allowing it to skate a mere 20 feet off the water at 300 mph.

The idea of an airplane that weighs as much as seven fully loaded Boeing 747s, and that doubles the distance it can travel by scooting over the ocean surface like a waterbug, may seem far-fetched. But the engineers at Phantom Works, the secretive Boeing think tank, have begun designing this enormous machine because the Pentagon has a major problem that has defeated many less harebrained efforts over the past 40 years. That problem? Mobility. The U.S. Army is a powerful force, but it is too large and has too much heavy equipment to move at a pace suitable for a fast-expanding conflict. For hauling the Army’s equipment, ships are slow and airplanes are small-one division may have more than 300 70-ton Abrams tanks. Even the huge C-5 Galaxy cargo airplane can carry only two Abramses, and the entire Air Force has 126 C-5’s.

Defense transformation is eventually supposed to result in a smaller, nimbler Army. But the Pentagon’s goal is to move that force faster than it can today, putting a full brigade-3,000 people and 8,000 tons of equipment-on the ground anywhere in the world within 96 hours. John Skorupa, a retired Air Force colonel who now heads the strategic development office of Boeing’s Advanced Airlift and Tankers division, dealt with this challenge in his previous job as commander of Air Mobility Command’s Battle Lab. “It was clear to us that we never had enough airlift. When we looked at global reach lay-down”-airlifters’ jargon for putting forces on the ground-“the airbridge took an enormous number of sorties to move a force of any significance.”

In early 2000, Skorupa, by then at Boeing, took the matter to Blaine Rawdon, a veteran Phantom Works designer who began focusing on the problem with engineer Zachary Hoisington. They knew that the Army was considering airships and airship-airplane hybrids designed to carry multimillion- pound payloads. Rawdon broadened Skorupa’s question and looked at a wide range of solutions to the Army’s problem, from a new generation of faster small commercial ships to airships to a large, conventional jet airplane, like a quadruple-size C-5. The value of speed always caused airplanes to come out ahead of airships and even the fastest marine vessels, but expanding aircraft to multimillion-pound payloads is not easy and would likely cost more than even the Pentagon can afford.

But ekranoplans, a specific type of WIG with short wings and jet boost for takeoff, seemed to offer some potential-as well as dramatically lower costs, if the concept could be made feasible. WIG aircraft had attracted an enormous amount of U.S. interest after the breakup of the Soviet Union, and in 1993 the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency looked into what the Russians had done. Boeing’s studies confirmed DARPA’s conclusion, as well as that of several Russians, that only a very large ekranoplan made sense, but also that the Soviet vehicle that came close had several inherent problems, mostly relating to its enormous weight. The 500-ton prototype, KM, completed in 1966, had 10 jet engines, two in the tail and eight attached to the forward wing. The 10 engines gulped fuel, and the aircraft had to reach 210 mph before it lifted off the water. The reinforced hull-necessary to withstand the pounding of the waves-significantly increased weight and reduced payload. But despite these weaknesses, the Russian achievements were impressive, according to former DIA analyst Stephan Hooker, who was one of the people in the Green Room on that day in 1967. The plane had less drag than an airplane of the same size, and the Russians had solved many stability and control issues.

But the Soviet Navy’s commanders were never enthusiastic about the program. Though the Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau, which constructed the prototype, built two more large ekranoplans-a 140-ton amphibious landing craft and a 400-ton vehicle armed with six anti-ship missiles-the Navy was already building large hovercraft for amphibious assaults and had bombers to strike NATO warships. Plus, the ekranoplans lacked the range to be useful as transports. The Navy accepted five out of a planned fleet of 140 and used them for trials, but none ever became operational.

Aware of this long, painful history and the many inherent challenges of WIG aircraft, Boeing engineers have revived the concept, with a key twist. The craft they’re designing is a cross between a land-based airplane and a Soviet WIG. It exploits the WIG effect, but it can fly like an airplane over terrain and land at an airport. It doesn’t need the ekranoplan’s thick, heavy boat hull, or extra power to haul itself out of the water. It has become the Pelican, sharing its broad, drooped wings with the birds that swoop over California’s coastline.

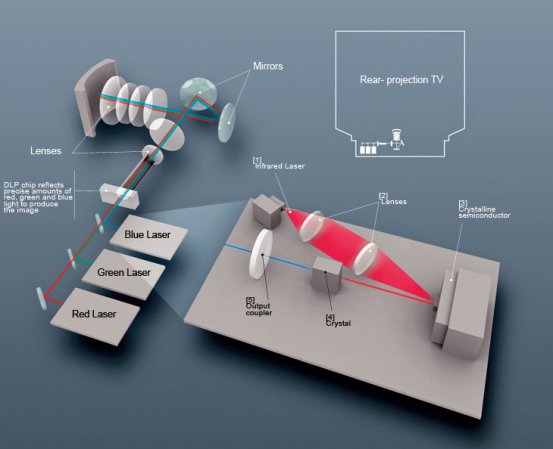

The Pelican, as currently envisioned, will be capable of flying at the same speed and height-300 mph, up to 20,000 feet-as most other airplanes powered by turboprops (jet engines geared to propellers, which, at Pelican’s speed, are more efficient than standard jet engines). The difference is that it will cover significantly greater ranges while hugging the water’s surface and taking advantage of the ground effect. There are two elements to the phenomenon. A wing lifts an airplane because the pressure beneath it is higher than the pressure above it-a result of the wing’s shape and forward movement. At the lateral tip of the wing, the high-pressure air underneath flows around to the upper surface. This creates a vortex, a rotating airflow that robs the wing of lift. But if the aircraft is flying very close to the surface, there is no room for the vortex to develop properly and it becomes weaker. The second element of ground effect is “ram pressure.” The higher-pressure air under the wing cannot escape downward, as it could at higher altitudes, and a cushion of trapped air forms under the wing. An airplane in ground effect can fly on less power, using less fuel, than one at high altitude.

Two numbers define the strength of the ground effect: the airplane’s wingspan and its flying height. The aerodynamic support generated-or benefit, in aviation jargon-is proportional to the span divided by the height. The increased aerodynamic support is one of the huge differences between the Pelican and the Russian ekranoplans. “It’s a function of span,” says Rawdon, “and that’s why a very large WIG makes sense.” With its 500-foot wingspan, the Pelican gets a “slight benefit” at 100 feet. “It goes up at 50 feet. At 20 feet, it’s really good. If we could fly at 10 feet, we would.”

If built, Boeing’s Pelican will be powered by four pairs of 80,000-hp turbine engines, similar in size to the gas turbine engines used today in large ships. These will spin four pairs of 50-foot, eight-bladed, counter-rotating propellers-more than twice the size of any propeller in history. The cargo hold will be unpressurized, which will help make the airplane significantly easier to build-its vast size notwithstanding.

Flying the Pelican will be a bit more complex than piloting conventional aircraft. Before a flight, crews and mission planners will use radar and photo imagery from satellites to check the weather en route, in order to exploit tailwinds and avoid storms. If the straight-line route lies across a landmass, the crew can decide whether it is better to fly around it or jump over it. Even if the ocean is raging, the engineers are confident that the airplane should be able to cruise at very low altitudes most of the time. “We grow up watching Victory at Sea on television or The Perfect Storm at the movies, and we naturally have the view of the ocean being tumultuous and violent,” Rawdon says. “But the majority of the time it’s relatively quiet, serene and flat.”

But Hooker, the former DIA analyst, thinks that even over a quiet ocean, the Pelican will be a handful. “The uglier it is in free air, the better it is in ground effect, and vice versa,” he cautions, meaning that Boeing’s choice of a long, thin wingspan over a short, stumpy one may make the Pelican excessively hard to control, giving it a spongy, undulating ride. One lesson from the ekranoplans, he explains, is that the vortex under the wing acts like a spring, yielding resistance between the airplane and the surface. With a stubby ekranoplan wing, the vortex is a stiff spring like that of a racing car. A long-winged WIG floats like a Cadillac, making control more complex.

But Boeing is anticipating some complicated maneuvering, so the controls will be highly automated; nobody is going to hand-fly the monster at 300 mph and 50 feet up. High-resolution radar will scan the sea ahead for ships, and the automatic control system will either turn to avoid them or lift the big airplane over them. On the ground, the challenge will be steering the Pelican-with 76 wheels arrayed centipede-like under its body-around taxiways designed for airplanes half its size.

Hooker will watch with interest as Boeing continues its investigations in this area. He led a design study for a large ekranoplan, which included a look at whether a several-thousand-ton vehicle could use conventional airports. “It’s not the runway,” he says. “Most airports are located on high water tables, and the taxiways and aprons are built on round gravel.” A giant vehicle, he says, sets up a long, gentle seismic wave. “First you get cracks in the toilets in the terminal building and after a few months, things start to fall down.”

Will the Pelican fly, or join so many WIG concepts in short chapters of the aviation history books? Fortunately, Pelican should not require any breakthroughs in basic technologies, such as structures or propulsion. The next step, the engineers say, would be a three-year program to build and test a subscale Pelican. This wouldn’t be a small airplane-it will need to be big enough to explore the ground effect over calm water-but it would be a simple one, using off-the-shelf technology. If the Army’s mobility study shows that the Pelican could be useful, work could start late this year or in early 2004.

But the Pentagon may not be the biggest market. The Boeing team’s commercial-airplane colleagues have informally discussed the Pelican with commercial cargo operators. The airplane carries 10 times as much payload as any current craft-as many as 180 standard 8- by 8- by 20-foot containers -and is 10 times faster than a ship. Unlike a ship, it could deliver cargo directly between major cities, eliminating sea-to-land transfers. The idea of a vast oceanic fleet of flying container ships may seem outlandish, but so, in their day, did mass-market air travel, stealth aircraft and satellite TV. In the end, ground-effect flight may not just be for the birds.

**Bill Sweetman is a contributing editor to Popular Science.

**

**LOOKING BACK: THE “FLYING LUMBERYARD”

**

Howard Hughes builds a mostly birch behemoth.

In December 1947, Popular Science reported that the H-4-an airplane weighing about 300,000 pounds,

with a 320-foot wingspan-flew for about a mile over Los Angeles Harbor. Detractors had scoffed that the Spruce Goose, as it was known, would never get off the ground, so the moment was a triumph for the plane’s designer and pilot, eccentric millionaire Howard Hughes. But it was a moment not to be repeated.

Like the Pelican, the H-4 was built to carry troops and weapons long distances. Hughes’ partner, shipbuilder Henry Kaiser, came up with the idea during World War II, when Nazi U-boats were attacking Navy transport ships. Because aluminum was being rationed, Kaiser and Hughes built their behemoth from wood (mostly birch, not spruce). Government support for the H-4 began to wane after the war: One senator called it a “flying lumberyard.” Still, Hughes persisted (by then he and Kaiser had gone their separate ways), investing millions of his own in the project. Not long after the Spruce Goose’s 1947 debut, though, government funding dried up and it became an instant relic, never to fly again. Today it’s on display at the Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.-Greg Mone