In the Czech Republic, a frozen lake’s emerald green ice is giving biologists an unprecedented opportunity to study a strange—and ominous—natural phenomenon. At the end of 2025, researchers at Czech Academy of Sciences traveled to Lake Lipno in South Bohemia to collect and examine samples from a rare cyanobacteria bloom in the dead of winter. Their findings could help better understand a problem that threatens both local marine life and nearby human populations.

Like many bodies of water, Lake Lipno is no stranger to cyanobacteria. The photosynthetic blue-green algae typically flourishes during the warmer months of summer and autumn, particularly in an environment with excess nutrients—a process known as eutrophication. Cyanobacteria blooms are notoriously foul-smelling, but the real issue is the damage they wreak on local ecologies. Each bloom produces exponentially growing waves of cyanotoxins that can poison and even kill nearby aquatic organisms. Unfortunately, these algae incidents are increasing due to climate change and human pollution, particularly industrial phosphorus runoff.

In the Czech Republic, most freshwater reservoirs usually see cyanobacterial blooms dissipate by the end of September. However, Lake Lipno has long experienced longer algae seasons. Marine biologists have repeatedly recorded sizable cyanobacteria populations through November, and occasionally into December and even January. Similar conditions at the end of 2025 allowed a biomass of algae to linger near the lake’s surface until the water began to freeze. According to researchers, weeks of sunshine, calm weather, and fair wind conditions were likely to blame. They also confirmed that their field samples contained the common cyanobacteria species Woronichinia naegeliana.

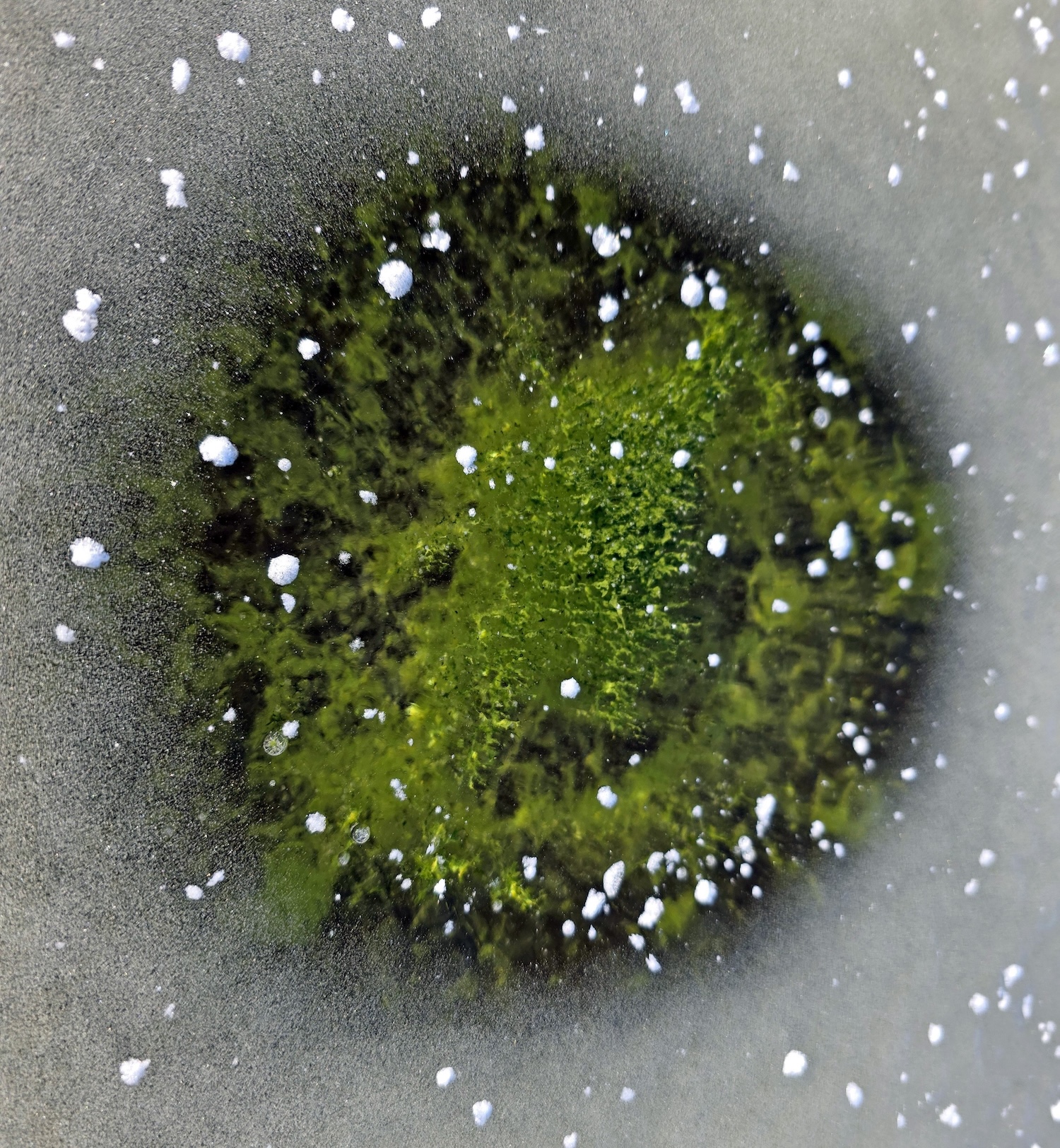

While the thin ice cover was itself transparent, the cyanobacteria retained its telltale green color that could easily be seen from the shore and overhead. A brief warm spell near December 24th melted some of the ice, which then refroze . The differences in solar radiation absorption allowed these new patches of clear ice to develop over darker areas of algae, forming what are called “cyanobacterial eyes.” The bloom only dissipated after heavy snowfall finally blocked enough light from reaching it beneath the ice.

It’s unclear how these icy winter blooms will affect their ecosystems, but unfortunately, similar incidents will almost certainly become more common—both at Lake Lipno and in other waters around the world. In the United States, it’s possible that cyanobacteria sightings could soon stretch into December or even January.

“Green ice on Lake Lipno fits into the long-term changes we observe here in connection with eutrophication and ongoing climate change,” said hydrobiologist Petr Znachor. “It suggests that we may witness similar surprises more frequently in the future.”