Cotton Vs. Polyester: Which Gym Clothes Trap The Most Body Odor?

European scientists explore the microbiome of dirty, stinky workout gear.

Chris Callewaert wants to solve body odor, starting with your gym clothes.

He and a team of European microbiologists have tackled a stifling mystery that permeates locker rooms and laundry hampers across the world: Why does gym gear reek even days after a workout?

A fair assumption would be that some fabrics trap more sweat than others, but perspiration on its own is sterile and does not produce foul odors.

Instead, pungent bacteria from our skin grow more readily on certain workout shirts, namely those made from synthetic textiles like polyester, according to new research from Callewaert and his colleagues at Ghent University in Belgium.

The scientists had 26 healthy individuals – 13 men and 13 women – participate in a spinning class, while wearing T-shirts made from natural or synthetic fibers. After the exercise, the shirts were stuffed into plastic bags and stored in the dark, akin to tossing gym clothes into a musty locker. After 28 hours, an independent panel of odor connoisseurs judged that the polyester shirts stank worse than cotton-based ones.

Skin germs feast on chemicals in sweat, turning them into pungent odor compounds, which the bacteria subsequently “fart” out.

Next, the researchers swabbed the shirts’ armpit regions for bacteria. Skin bacteria produce many of the scents connected to bad body odor — and armpits are microbe havens.

To understand just how prolific bacteria are on our bodies, grab a ruler and pen. Draw a square one centimeter by one centimeter on your forearm. Around 100 bacteria live inside that square. In contrast, an identical square on your armpit, navel, or toe web spaces carries 10 million bacteria.

The most common known cause of malodor is a family of skin microbes in the genus Corynebacterium; however, the scientists couldn’t spot any on sweaty gym gear.

Rather they found that soiled polyester shirts wound up harboring more Micrococci bacteria, a type of odiferous germ, than cotton shirts. The result was surprising because Micrococci don’t generally grow in pits.

“As part of a separate, ongoing study, we’ve screened over 200 people, and found very low levels of Micrococci present on armpit skin,” says Callewaert. “Something about sweat-filled polyester enriches these sour-smelling bacteria.”

Micrococcus luteus

Skin germs feast on chemicals in sweat, turning them into pungent odor compounds, which the bacteria subsequently “fart” out. While natural textiles absorb this stench-filled water, Callewaert and his colleagues suspect that the funky juice pools in the microscopic spaces in between synthetic fibers, creating a great environment for bacteria to flourish.

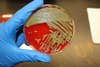

To explore this idea, the team took a few pungent species of bacteria and tried growing them in Petri dishes coated with seven different fabrics: polyester, acryl, nylon, fleece, viscose, cotton, and wool.

The results were mixed. Cotton grew very few smelly germs, akin to earlier findings, while the microbes continued to swarm over polyester.

Synthetic nylon was a great refuge for Propionibacterium acnes, a species of bacteria that causes acne and foot odor. Natural wool supported every germ tested, while the scientists found one fabric – viscose – where bacteria didn’t grow.

This preliminary study could help inform clothing makers on how to create less smelly apparel.

“Many manufacturers have started adding antimicrobials, like nanosilver, to their clothes,” says coauthor Nico Boon, a microbial ecologist at Ghent University.

Such chemicals eliminate germs indiscriminately, meaning the good germs disappear with the bad. “This could potentially throw off our immune systems,” Boon continues. “We should manage and control the existing microbial community, so that we steer the germs in the way that we want, instead of killing everything,”

To keep garb from trapping workout odor, he and Callewaert recommend clothing hybrids, where the fabric coming in contact with armpits is made from cotton. The rest of the shirt could be synthetic fabric, which accumulates less heat and feels more comfy.

The researchers published their work in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.