Why Testicles Are The Perfect Hiding Spot For Ebola

Gonads provide a safe haven for the virus, which is bad news for Ebola survivors who want to have sex

On March 20, a woman in Liberia was diagnosed with Ebola. It was a mysterious case, since it happened 30 days after the country’s last recorded occurrence of the virus, and Ebola is thought to be contagious for up to 21 days at most. The woman reported no contact with the Ebola virus or anyone from Guinea or Sierra Leone, where outbreaks are still ongoing. She didn’t travel anywhere, and she didn’t attend any funerals. Her only known link to the disease was having unprotected sex, on March 7, with a man who was hospitalized for Ebola back in October.

Scientists knew that the Ebola virus could live on in a man’s semen for up to 82 days, but until now, there’s only been one case of the disease possibly spreading through sex. That was in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1995, and the results were inconclusive.

In the Liberia case, doctors didn’t find any evidence of the virus within the man’s blood, but tests revealed that his semen contained Ebola virus RNA closely matching the strain that infected the woman. It’s not an iron-clad proof of causation–doctors don’t know if there was any fully formed (and therefore infectious) virus in the guy’s semen–but it’s pretty strong evidence that the disease could be spread sexually.

Previously the World Health Organization advised Ebola survivors to abstain from sex or use a condom for up to three months after getting sick. Now that it looks like the disease can be spread up to five months later, doctors no longer know when it’s safe for Ebola survivors to return to a normal sex life.

Suppressing the immune system may be good for sperm, but unfortunately it’s also good for pathogens.

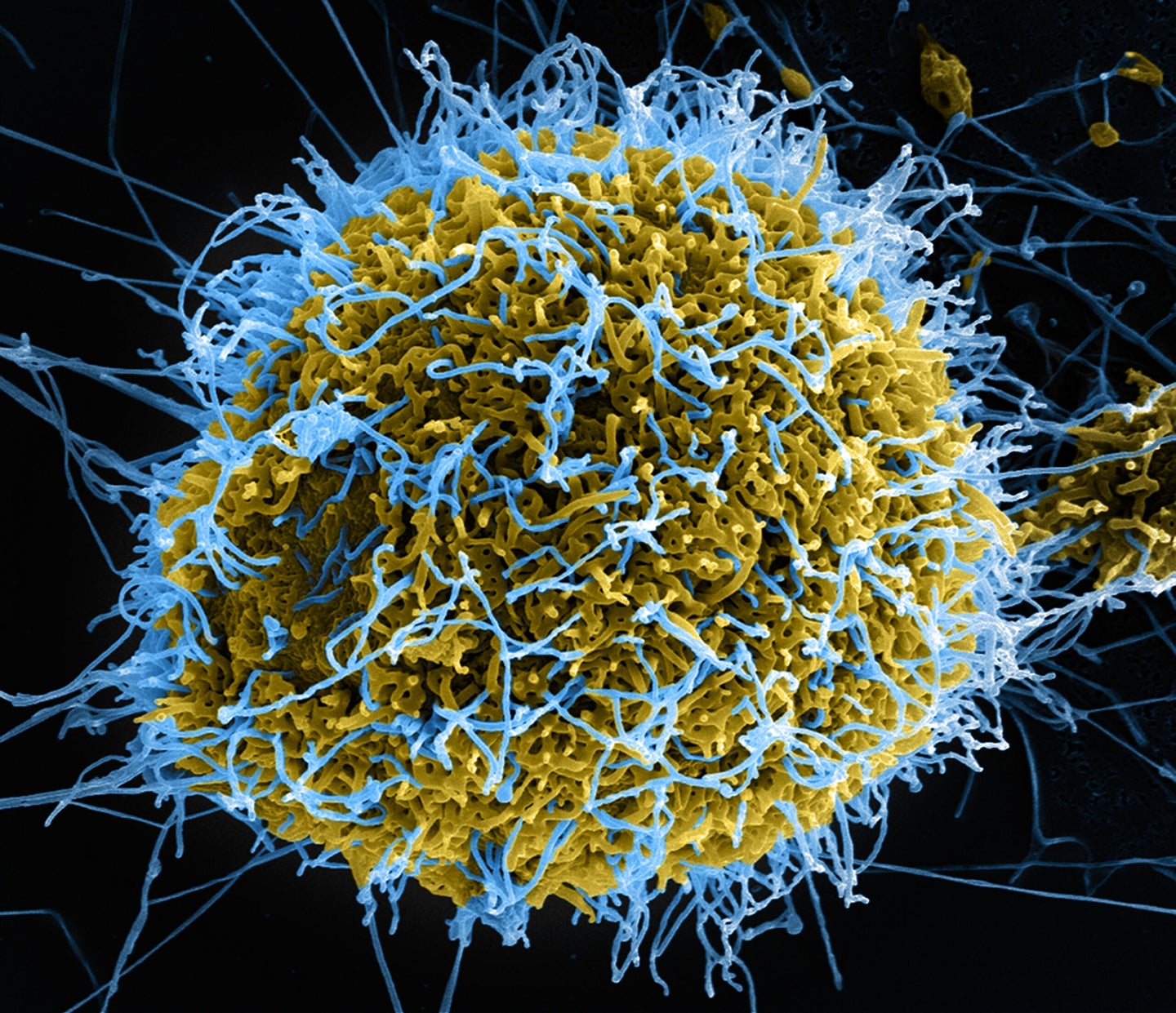

So how is it possible for Ebola to live longer in the testes than in other parts of the body? It likely has something to do with the body’s “immune privileged” areas. A person’s brain, eyes, and gonads are so important to survival and reproduction that they’re actually shielded from the body’s own immune system. That’s because the same molecules that can fight off foreign invaders can also damage nerves and other cells. And it doesn’t help that the immune system doesn’t play nicely with sperm. White blood cells see the little spermatozoa as invaders–probably because males don’t start producing semen until after the body’s immune system has already been established.

The testes (and other privileged sites) are protected from the immune system by a wall of cells. This blood-testis barrier surrounds the tubes where sperm are made, making sure immune cells can’t move from the blood into the tubes. Should the barrier be breached, the testes are armed with immunosuppressive molecules that would cripple any invading immune cells. While the testes do have a resident population of macrophages and T-lymphocytes (both cells that fight infection), their ability to kill intruders is also suppressed to protect the developing sperm.

Suppressing the immune system may be good for sperm, but unfortunately it’s also good for pathogens. Once a virus infiltrates an immunologically “privileged” area like the testes, it can be hard to get rid of. This is one of the factors that makes HIV so difficult to treat.

It could also spell trouble for companies that are trying to develop Ebola treatments, says Columbia University epidemiologist Stephen Morse. However, scientists have been working out how to ferry medicines across similar barriers in the brain, so those methods may help here, too.

But first, scientists need to confirm whether or not Ebola is sexually transmissible. If so, how often does that happen, and who is most at risk? To figure that out, the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are going to need to analyze a lot more semen samples from Ebola survivors–particularly since sexual transmission seems to happen so rarely.

The largest Ebola epidemic in history, the outbreak in West Africa caused more than 26,000 infections and killed 11,000 people. But it also helped doctors learn how to manage the disease better, and that means there are a lot more Ebola survivors than ever before. The larger numbers makes it easier to spot rare events such as the sexual transmission of Ebola.

Hopefully those large numbers will make it easier to figure out when it’s safe for Ebola survivors to return to a normal sex life. “People may want to have children–they may have lost children, and want to go back to normal as soon as possible,” says Morse. “It was hard enough to wait three months, and now it’s going to be harder.”