Sweat Sensors Track Athletes’ Health

Coming soon to a fitness tracker near you

You might not know it, but your sweat is pretty valuable. The varying chemical concentrations in sweat reveal your blood sugar level, whether you’re dehydrated, or if your blood is not pumping fast enough to a particular tissue. Now a team of researchers led by scientists at the University of California, Berkeley has developed a Fitbit-like device that can detect and track the molecular components of sweat, according to a study published today in Nature. Devices like these could help doctors and fitness aficionados track multiple variables of athletes’ health, and could someday provide a non-invasive test for medical professionals working to diagnose disease.

Though sweat is mostly water, it also contains dissolved chemicals and minerals that can give scientists some insight into what is going on inside the body. The researchers designed their sensor to detect sodium, potassium, glucose, and lactate from sweat. Sodium and potassium concentrations can show if a person is dehydrated, lactate concentrations reveal muscle fatigue, and glucose levels in sweat correlate to glucose levels in the blood, which affect an athlete’s energy level and alertness. The researchers created a small plastic biosensor to pick up on these chemical concentrations.

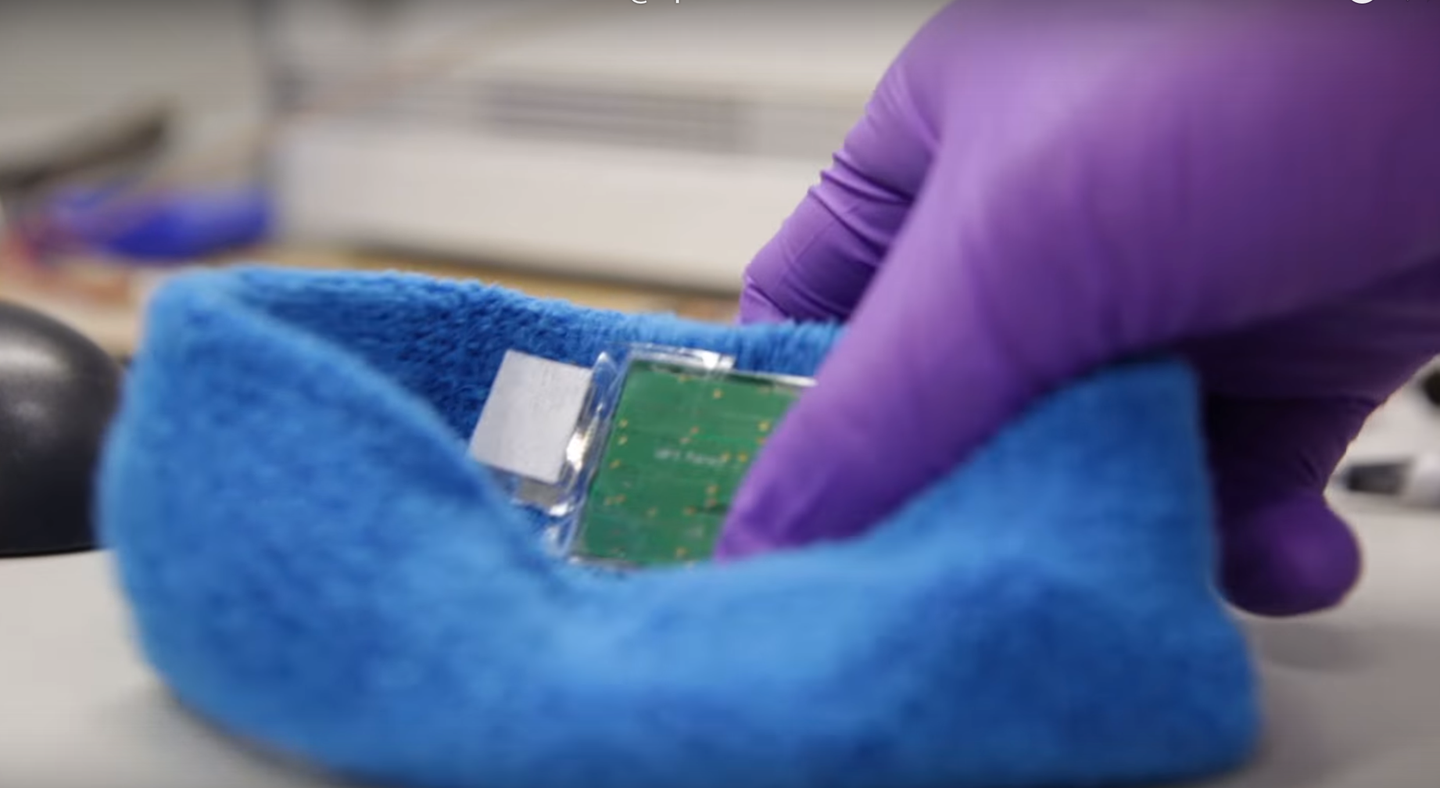

Sweat sensing device in action

But the levels of these compounds are often unsteady as a person sweats, so to counteract those small changes, the researchers included a calibrating tool on the microprocessor attached to the sensor.

The device, which is flexible and can be worn on the head or wrist, can also detect the temperature of the person’s body. Processors on the device analyze the data before wirelessly transmitting it to a nearby cell phone or computer.

This isn’t the first time scientists have developed sweat sensors as a way to understand what’s going on inside the body—doctors have used them for decades to diagnose cystic fibrosis in infants and to determine if a patient is addicted to drugs. But with the recent trend towards fitness monitoring devices, many researchers (including those on this competing team at the University of Cincinnati) have found new biomarkers in sweat to provide additional information to clinicians and athletes alike. But this device appears to be the most specific–and capable of measuring more biomarkers that correlate directly to health–to date.

That kind of real-time information can be useful for professional athletes during training or competitions to track their physical condition. But it could also be useful for doctors and researchers who need to monitor patients or research subjects. “A medical technician could get a reading on somebody instantaneously and follow that, instead of taking a blood sample then sending that to a laboratory and waiting several hours for a result,” says George Brooks, a professor of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley and one of the study authors.

Participants in scientific studies could generate a huge amount of data by wearing the sensors, which would help researchers better understand the relationship between biomarkers in sweat and a person’s overall health status.

The researchers don’t give a concrete timeline for when their device might go on the market, but with any luck, it could soon end up in clinical settings or even replace the Fitbit as the hobbyist’s fitness tracker.