Important Scientific Mystery Solved: How Birds Lose Their Penises

The penises of many male birds stop growing and shrink away. Scientists reveal the genetic mechanism at work.

A team of researchers at the University of Florida has solved the mystery of what some call “one of the most puzzling events in evolution”: the reduction and loss of the penis in most male birds.

About 10,000 species of birds have reduced or absent external genitalia as adults. Many have normal penises as embryos, but as they develop, their penises stop growing and shrink away. (Despite that, male birds still manage to fertilize female birds through internal insemination, just like humans. We’ll get to how in a moment.)

To study how male birds lose their penises, the UF researchers examined the embryonic development of birds with penises (ducks and emus) and birds without penises (chicks), among other creatures.

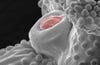

A developing penis of a chick embryo

What they found was that a critical gene called Bmp4 switches on, causing developing genitals to wither away. In other birds like ducks and emus, that gene stays switched off, allowing their penises to grow fully. (In some birds, they grow a little too fully: certain species of water fowl, like ducks, have such large phalluses, they can exceed the length of the body.)

“Our discovery shows that reduction of the penis during bird evolution occurred by activation of a normal mechanism that attenuates development—programmed cell death—in a new location, the tip of the emerging penis,” says Martin Cohn, a professor at UF’s Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a senior author on the study.

Cohn and his colleagues believe their research could shed light on evolutionary developments beyond the fowl world. It could “lead to discoveries of new mechanisms of embryonic development, some of which will be totally unexpected,” Cohn says. “This allows us to understand not only how evolution works, but also to gain new insights into possible causes of malformations.”

Birds have clearly figured out how to make do, given that they’ve have had no trouble replenishing the flock. Chickens perform what is called the cloacal kiss, in which the male and female must cooperate in order to transfer sperm between their opposing cloacae.

But that still leaves the question as to what evolutionary function a missing penis could possibly have.

Says Ana Herrera, UF graduate student and lead author on the study: “One idea is that choosing to mate with males who have a reduced or absent penis confers some advantage to females by giving them control over copulation and the paternity of their offspring.”

Their findings will be published in this week’s journal Current Biology.