The Science Of PSAs: Do Anti-Drug Ads Keep Kids Off Drugs?

The U.S. has been pouring millions of dollars into anti-drug campaigns since the 1980s. Has it done any good?

From Reefer Madness to Nancy Reagan’s famous “Just Say No,” we’re constantly trying to convince kids that drugs aren’t as fun as they think they are.

Drug Week

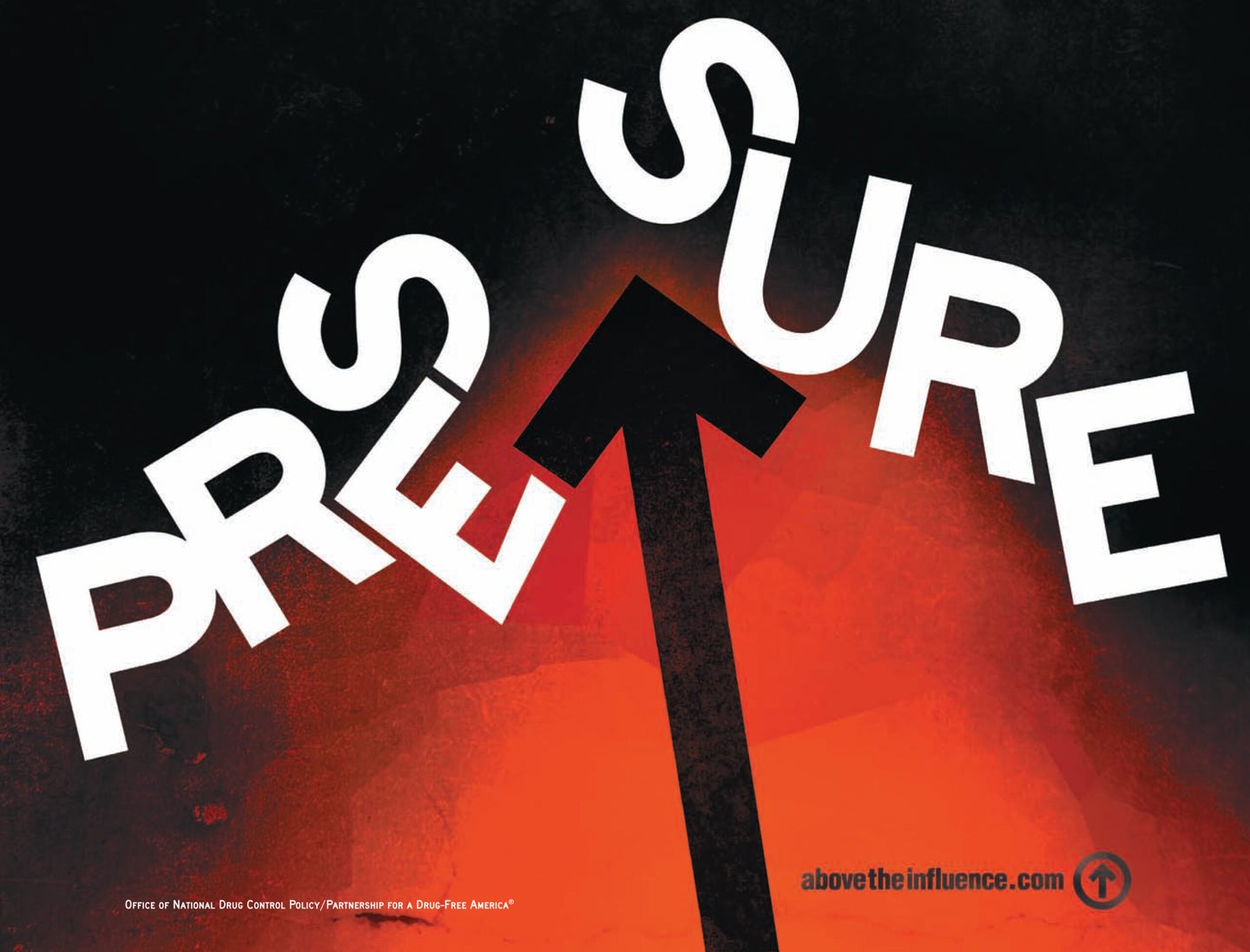

The Office of National Drug Control Policy, established in 1988, runs the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign, a propaganda machine created to stop kids from using drugs and the money behind anti-drug ad campaigns like “My Anti-Drug” and “Above the Influence.”

Since it was established in 1998, the government has poured hundreds of millions of dollars a year into buying ad spots for anti-drug propaganda. But does it work?

Carson Wagner, now an assistant professor of journalism at Ohio University, wrote his 1998 Penn State master’s thesis in media studies on the counter-intuitive effects of anti-drug ads. He demonstrated that for some kids, seeing anti-drug ads made them curious about what doing drugs would be like, even if they had never had that curiosity before.

When anti-drug ads say “don’t do drugs,” they inherently bring up the implicit question “should I do drugs?” The ads can draw attention to a gap in what the viewer knows about drugs, making them more curious. It’s like when you miss a call from an unknown number — the phone ringing prompts you to wonder “who was it?”

In a 2008 study, participants who were primed with anti-drug PSAs were more curious about using drugs than those that hadn’t seen the PSAs. Wagner and his co-author, S. Shyam Sundar, found that because anti-drug ads made the viewer think more about drugs, it could also lead them to believe drug use is more prevalent than it really is. “These results should be seriously considered, as it has been consistently recognized in psychological research that curiosity is one of the most potent motivational forces for human behavior,” the paper warned.

Advertising is normally all about grabbing your attention, but Wagner says that’s a bad way to reduce drug use. The “drugs fuel terrorism” ads that ran during the 2002 Superbowl certainly garnered more ridicule than anything else:

As a BBC News feature put it in February, ” a surprising number of anti-drugs campaigns around the world still fall back on scare tactics and, in particular, the drug-fueled ‘descent into hell.'”

“It’s not often so much a matter of what makes anti-drug ads effective,” Wagner says. “It’s more about how we watch them that moderates their efficacy.” If you’re not paying close attention to the ads, they can actually work better, his research has shown, by subtly transmitting the message connecting “drugs” and “bad” rather than the equivalent of repeating it loudly in patronizing caveman-speak.

In the U.K., the “Talk to Frank” campaign has tried to provide a more honest, nuanced portrait of drug use, one that encourages people to call the Frank hotline for advice. But there still isn’t direct evidence to prove that it’s dissuading people from taking drugs in the first place.

In the U.S., the “Above the Influence” campaign has tried to embrace the advice of Wagner and other researchers: to find out what kids who don’t use drugs do, and advertise those activities. “What they’re doing is showing more alternative activities,” he says. “They’re not bringing up the notion of drugs.”

It’s developmentally part of being a teenager to buck adult rules and take moderate risks.Research shows the new campaign at least somewhat effective. A 2011 study on “Above the Influence” found that only 8 percent of teenagers who were familiar with the campaign started smoking pot, versus 12 percent of teenagers who hadn’t seen it.

Michael Slater, the study’s principle investigator and a professor of social and behavioral sciences at The Ohio State University, says initial anti-drug ads didn’t take into account the nature of being a teenager.

“Research shows that at least half of teens are sensation-seeking. Taking chances is exciting,” he explains. “It’s developmentally part of being a teenager to buck adult rules and take moderate risks.”

“Drug use is implicitly seen as a way to become autonomous and independent from your parents and everybody else,” says Slater, who worked on a campaign aimed at middle schoolers called “Be Under Your Own Influence.” It tried to show kids that being stoned or drunk doesn’t make you independent or successful.

It’s difficult to make anti-marijuana and alcohol PSAs because kids aren’t necessarily convinced the risks are plausible. Whereas with harder drugs like meth, negative consequences like addiction or rotting teeth seem more immediately dangerous to teenagers, with marijuana, they “recognize that the risks are real but they usually don’t happen.”

Even without heavy-handed ad campaigns, convincing kids not to do drugs is a tricky beast. A recent study found that when parents admit to their drug use to their children, even as part of an anti-drug discussion, their children were more less likely to think drug use wasn’t a big deal.