DARPA’s Brain-Controlled Robotic Arm Fast-Tracked, Could Be Available in Just Four Years

Usually when we report on DARPA’s robotic, brain-controlled prosthetic arm, we’re reporting on news from the lab. Soon we’ll be...

Usually when we report on DARPA’s robotic, brain-controlled prosthetic arm, we’re reporting on news from the lab. Soon we’ll be reporting from clinical trials. On Tuesday the Food and Drug Administration said it would fast-track the DARPA device, pushing it through the approval process with priority assistance in order to get it to amputees—many of which are returning from combat zones—as soon as four years from now.

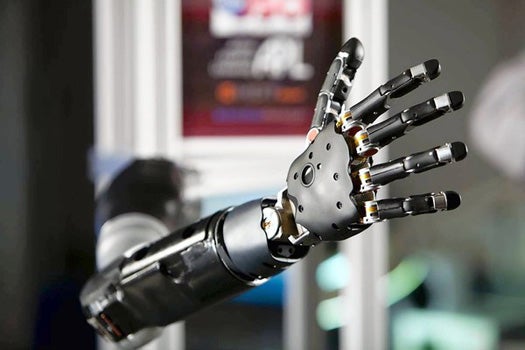

There are really two headlines here; first, the DARPA arm is a modern marvel that’s taken several years, $100 million, and some of the best minds in prosthetics design, robotics, and brain-machine interfaces to develop. It marks a technological leap—a prosthetic arm that is robotically controlled via a chip in the brain, making it more like a real limb than any approved prosthesis before it.

We expect the well-funded blue-sky thinkers at DARPA to identify a problem—in this case, the large numbers of American service members returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with limbs severed by IEDs—and quickly turn around a technological solution. We expect the exact opposite from the FDA. But long viewed as a place where innovation goes to die, the FDA is attempting to remake itself into a bureaucracy capable of moving innovative technologies from lab to market faster (that’s the second headline).

In the FDA’s defense, its job is not easy. Applicants bring the agency technologies and drugs never seen previously in the history of the world and ask scientists there to assess them for safety—a difficult job to say the least. The fast-track review—a new initiative that aims to bring technologies or drugs considered most important to market faster—will offer companies or agencies an FDA case manager to cut down on bureaucratic snafus and will give those products priority access to senior agency scientists in hopes of cutting the period of t review in half.

For DARPA’s arm, that means four or five years rather than a decade spent in the FDA approval pipeline. Within six months DARPA will begin implanting chips in five patients’ heads to begin clinical trials. Those patients will be monitored for a year to see if chip function degrades or if bodies reject the chips. If the trials are successful, that four or five year timeline for commercial availability is realistic.

Now if only DARPA could create a tool that cuts through red tape.