How The U.S. Coast Guard Is Fixing The N.J. Oil Spill Caused By Sandy

Petroleum tanks damaged during the storm spilled an estimated quarter million gallons of oil into New Jersey waterways. Now crews are working around the clock to clean it up.

Crews will be working for at least one to two weeks to clean up a storm-related diesel fuel spill on the New Jersey coast, according to a Coast Guard official.

The oil came from two 3.15 million gallon-capacity tanks at the Motiva petroleum storage facility, in Sewaren, N.J., damaged during Hurricane Sandy. Each contained 336,000 gallons of oil prior to the storm. The site is located on the Arthur Kill, a 10-mile-long, 600-foot wide tidal strait dividing mainland New Jersey from Staten Island, N.Y.

According to MarketWatch, Motiva has estimated that around 227,200 gallons of oil leaked from the damaged tanks. The Coast Guard has not confirmed that number. Two other nearby tanks, also holding 336,000 gallons of diesel fuel each, made it through the storm intact.

The Monday night surge from superstorm Sandy flooded a gravel-lined containment area around the tanks that was supposed to contain a spill. One tank has a visible hole, says Chief Ryan Egal of the U.S. Coast Guard, and the entire area is strewn with the kinds of debris that, carried by a hurricane wind or record-breaking storm surge, could cause a lot of damage to a fixed structure. “I’m seeing a lot of railroad ties, docks, a lot of wood, general garbage that is basically from land,” Egal says.

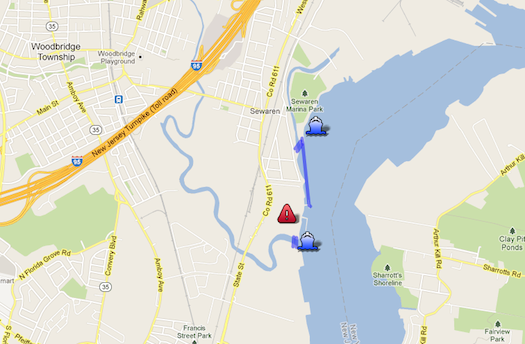

The storm surge both overtopped and breached the protective berm around the tanks, carrying spilled oil into surrounding waterways. Responders have seen “a lot of [oil] sheen” around Motiva’s dock on the Arthur Kill, and in the waterway’s main navigation channel, says Egal, as well as in nearby Woodbridge and Smith’s creeks. Responders have deployed 13,600 feet of containment boom so far around Motiva’s dock and at the creek mouths to contain the spill. No sheen has been sighted on the New York side of the waterway, Egal states.

By the numbers, around 150 personnel are using 14 skimmers, 9 vacuum trucks, and 3 shallow water barges with built-in skimmers, along with absorbent pads and booms, to collect spilled oil at Motiva. It will be impossible to recover and reuse any of it, Egal says. He describes working conditions that sound, to understate things, extremely challenging: Workers have trying to sop up oil and collect fuel-soaked trash in brisk winds, around several severely damaged marinas in Smith’s Creek—”boats stacked on other boats,” wrecked docks, Egal says. “They are working about 18 hours a day in the bermed-off area,” he says, running equipment off generators because there’s no power at the site. Night work isn’t possible until they can get sufficient power for lights.

“Also, a lot of the responders are local,” he says. “They come here and do this and then have issues at home.” More than 1.4 million homes and businesses in New Jersey were still without power on Friday, according to Reuters.

On the up side, regular air testing by the Coast Guard’s Atlantic Strike Team has turned up no problems so far for both clean up workers or the nearby residential community, says Egal, one of the team’s hazardous materials specialists. Oxygen levels are normal; there are no detected levels of carbon monoxide or hydrogen sulfide; and volatile organic compound levels are consistent with what might be created by regular street traffic.

Motiva has hired three oil spill response contractors in response to the spill, according to Coast Guard Petty Officer Stephen Lehmann: Atlantic Response Incorporated, Moran Environmental Recovery, and MSRC-Marine Spill Response Corp. The Coast Guard is advising and overseeing the effort, along with state and local officials.

The Arthur Kill flows along a largely industrialized section of the New Jersey coast, just a few miles south of Newark International Airport. But it’s got a gentler side as well: the New York bank is mostly saltwater marsh, and in New Jersey, conservation groups have counted around 90 species of wild birds breeding in the greater Arthur Kill watershed. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists several dozen “species of special emphasis” that call the Arthur Kill area home: plants and animals that aren’t considered threatened or endangered, but who depend heavily upon this environment to survive and thrive.

“The marsh areas are definitely a long term issue,” says Chief Egal. “We can’t go in there and clean up.”