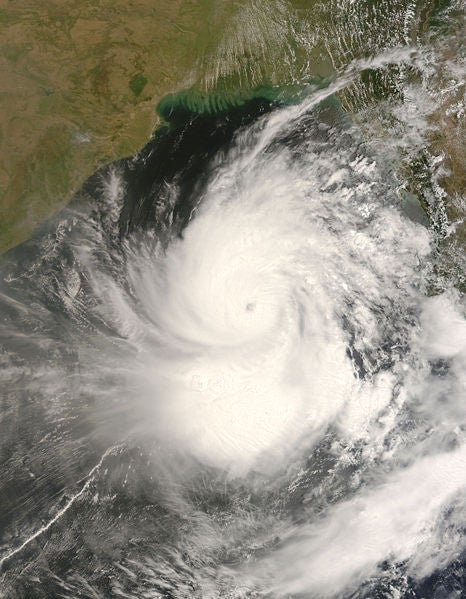

Ripple Effect in the Wake of Cyclone Nargis

A natural disaster that may have been preventable has a global impact

With a death toll steadily rising, the effects of Myanmar’s devastating cyclone have yet to be quantified, but days after the storm one thing is clear: they will be long-lasting and far-reaching.

“Our biggest fear is that the aftermath could be more lethal than the storm itself,” said Caryl Stern, head of the U.N. Children’s Fund. Four days on, electricity and water supplies are still cut throughout the country. With broken sewage lines, mounting trash, impassable roads preventing access to clean water and food, and damaged hospitals, the nation faces a likely-devastating public health crisis. The World Health Organization has pinpointed malaria and tuberculosis—two diseases that thrive amidst overcrowding and bad water—as especial threats. Meanwhile, the spread of communicable diseases is speeded by blocked roads, which trap sick people in and keep health workers out.

They also prevent the easy egress of rice: one of Myanmar’s major exports. Last year the country exported 400,000 tons of rice. Now, shipments to Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, which would have fed some of the world’s poorest, have been halted. While the government assesses the extent of damage to paddies and citizens clear the roads, these countries are turning to a market already stressed by increased emphasis on biofuels and rising oil prices, among others. Though it is unclear whether worldwide food prices will rise as a result; in Myanmar the cost of rice and cooking oil has already tripled.

The real tragedy surfacing from reports is that this fallout may very well have been prevented. In the wake of the 2004 tsunami, scientists studying the devastation discovered that dense and healthy mangrove forests slowed the massive waves and curtailed damage. Fish and shrimp farms, tourism and population growth have led to the worldwide loss of millions of acres of mangroves over the past few decades. The bulk of the harm caused by Nargis was attributed not to the storm, but to the waves—something the formerly mangrove-crammed coastline of Myanmar could have blocked. Meanwhile, the UN has fingered the government’s failure to install an early warning system as a major contributor to the loss of life; the cyclone formed five days before touching down.