New Onboard Converter Technology Harvests Auto Engine Exhaust to Generate Electricity

The key is something called skutterudite

Future cars may eat their own exhaust, converting heat from their emissions into electricity. The conversion can improve fuel economy by reducing an engine’s workload.

Purdue University researchers are working with General Motors to build thermoelectric generators, which produce an electric current when there is a temperature difference. Starting in January, the team will install an initial prototype behind a car’s catalytic converter, where it will harvest heat from exhaust gases that can reach 1,300 degrees F. The prototype involves small metal chips a few inches square.

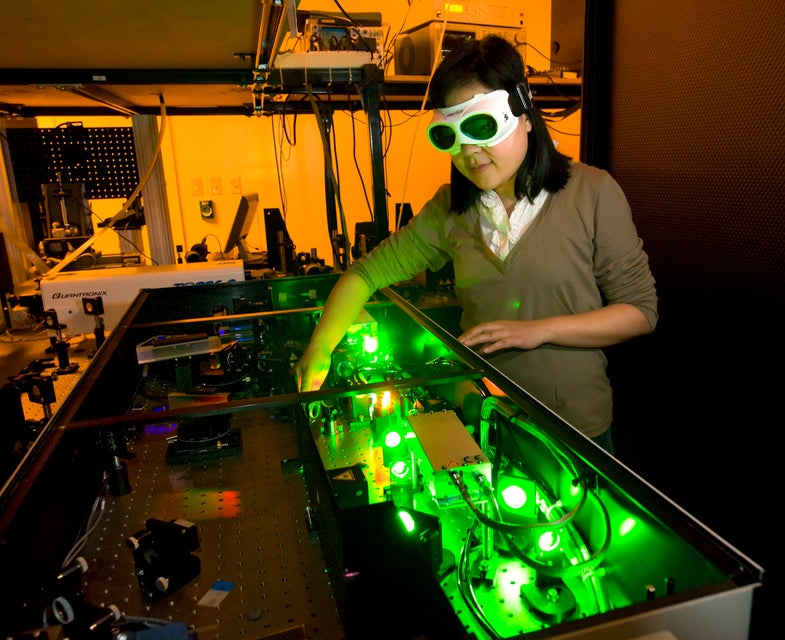

The process requires special metals that can withstand a huge temperature differential — the side facing the hot gases stays warm, and the other side must stay cool. The difference must be maintained to generate a current, explains Xianfan Xu, a Purdue professor of mechanical engineering who is leading the research.

One of the group’s biggest challenges is finding a metal that conducts heat poorly, so heat is not transferred from one side of the chip to the other. GM researchers are currently testing something called skutterudite, a mineral made of cobalt, arsenide, nickel, or iron. Rare-earth metals can reduce skutterudite’s thermal conductivity even more, but we all know how problematic rare-earths can be; to solve the problem, researchers are hoping to replace them with “mischmetal” alloys.

Thermoelectric technology has applications beyond powering cars — they could also be used to harness waste heat in homes and power plants, and they could power new generations of solar cells, Xu said. The work is being funded with $1.4 million from the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy.