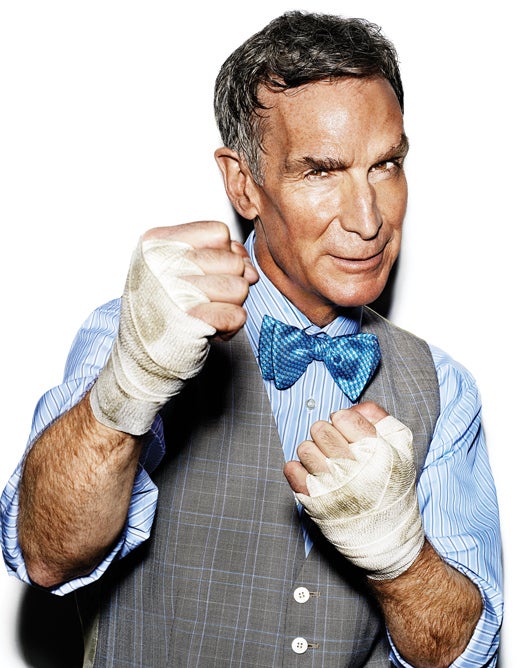

Bill Nye Fights Back

How a mild-mannered children’s celebrity plans to save science in America—or go down swinging.

Let’s say that I am, through my actions, doomed, and that I will go to hell,” Bill Nye said. He was prepping for a Super Bowl party and making pizza dough from a recipe given to him by his friend, Bob Picardo, who played The Doctor on Star Trek: Voyager. He ducked beneath the countertop, pulled out a KitchenAid mixer and a bag of flour, and then returned to the topic at hand, which was religion and science and what he believed.

“Even if I am going to hell,” he continued, “that still doesn’t mean the Earth is 6,000 years old. The facts just don’t reconcile.” He turned back to the mixer, sighed, and slumped a little. For a moment, Nye looked weary at the thought of ill-informed parents undoing his life’s work. “So,” he said, straightening, “the worst that can happen in this debate is I lose my temper, Ken Ham is suddenly empowered, his Ark Park gets built, and it’s all my fault.” Then he poured the flour into the mixer, along with some sugar, salt, and a packet of yeast, and flicked the switch. In a little more than 48 hours he would walk onto a stage in Petersburg, Kentucky, to debate Ken Ham, founder and leader of Answers in Genesis, a ministry most famous for owning and operating the Creation Museum, which displays animatronic dinosaurs next to Adam and Eve. Preparing for the debate—the responsibility he felt defending reason in the face of extreme faith—had weighed heavily on Nye. But now, making pizza dough, he was just a guy wowed by science, which was currently happening right in that bowl.

Over the mixer’s low hum, Nye explained that the yeast, a fungus, was slowly eating the sugar and excreting carbon dioxide and alcohol, which would eventually cause the dough to rise. He said this with the same Aww, shucks, isn’t this incredible? delivery that made him who he is today: the Science Guy, star of the 1990s megahit television show and friendly explainer of all things scientific. Nye turned off the mixer and removed the dough, working the sticky ball on a lightly floured counter before dropping it on a plate and walking around the corner to the den, where he placed it atop a cable box. He said the warmth of the electronics would speed the reaction of the yeast enzymes, making the dough rise more quickly. Next to the box, a small bookshelf contained the DVD set of all 100 episodes of Bill Nye the Science Guy. A few were missing, actually, on loan to some kids from his Los Angeles neighborhood. A framed sheet of paper hung above the shelf—the single-page mission statement Nye wrote while creating the show. At the top, he’d typed “Objective: Change the world!” He took it down and stared at it for a moment. Nye holds a deep fascination, a reverence even, for all we don’t fully understand. “We are literally made of the stuff of stars,” he said. “It gives me the willies—how can this be? How can we know our place in the universe?”

It was a rhetorical question. Nye had been setting up the same punch line for so long the answer had become his calling card, his signature shout-out: “Science!” But Nye is the first to admit that science in America is in a bad way. He said he felt that despite issuing more patents and Ph.D.s than any other nation, the country was drifting closer and closer toward scientific illiteracy. Just a few weeks earlier, a PEW research poll found that nearly 45 percent of Americans believed humans came to be by a process other than evolution. A similar poll found that one in two Americans don’t believe that humans are causing climate change, despite the fact that about 98 percent of all scientists do (a greater consensus than supports the link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer). To Nye, science is under siege, and he is not about to sit back and watch the thing he loves and staked his career on suffer.

He re-hung the framed printout, but not before repeating its message: “Change the world.” The world had changed since the show ended in 1998, and not necessarily for the better. So Bill Nye was venturing back into the fray to change it once more.

What kicked off the debate at the Creation Museum was simple. The whole business started in New York a few years ago. His publicist had scheduled a bunch of interviews, and Nye, up since 2 a.m., arrived at the last one, for a website called Big Think, in late morning. He was jet-lagged, tired. You can see it in the video—the way his head bobs, struggling to stay aloft. You can hear it, too. His voice comes from way back in his throat, all gravelly. The interviewer asked him about Pluto and dark matter, and then about creationism. Bill sighed and said, “When you have a portion of the population that believes in that, it holds everybody back.” The guy on screen looked so different from the funny, warm Science Guy known to a generation. He wasn’t at all funny, for starters. And his exasperation struck a chord. To date, the Big Think video has nearly 7 million views, and it prompted Ham to ask for a debate.

He looked so different from the funny, warm Science Guy known to a generation. He wasn’t funny at all, for starters.

This new, angrier, more-adult Science Guy hadn’t been there all along. His evolution goes back to the late 1970s in Seattle, when he first met Steve Wilson. Nye was an engineer at Boeing, fresh out of college, designing screws for the hydraulics systems of 747s, working on a stand-up routine at night, and volunteering at the Pacific Science Center on weekends. Wilson was a floor director on a show called Seattle Tonight Tonight, and Nye came on after winning a Steve Martin look-alike contest. When Wilson helped launch a show called Almost Live!, Nye started hanging around the writers’ room. “We kind of felt sorry for him,” Wilson says. “He’d make these jokes. We called them jokes of the future because they weren’t funny.” Nye learned that if he dipped a marshmallow in liquid nitrogen and popped it in his mouth, smoke came out of his nose, which got laughs. He could entertain people using…science!

Almost Live! was a local-access Letterman knockoff hosted by a fellow named Ross Shafer. One day a guest canceled, and Shafer mentioned to Nye that he had seven minutes to fill. “Why don’t you do that science stuff?” Shafer asked. “You can call yourself Bill Nye the Science Guy or something.” Nye thought: “Hey, that’s pretty good! It even rhymes!”

Almost Live! went national in 1992. By then it had morphed into a sketch comedy show, and Nye had quit Boeing and joined full time as a writer and actor who starred in recurring bits. The next year, Bill Nye the Science Guy premiered as a stand-alone show on PBS. It was zany and smart. It ran five seasons, won 18 Emmys, and is to this day watched by millions of children. Local PBS stations still air it, and Disney sells the complete DVD set to junior highs and elementary schools across the U.S., where kids are all but guaranteed to watch Bill Nye the Science Guy any day a substitute teaches.

As the Science Guy, Nye became famous in the rare and intimate way a person only can when a generation grows up with him. Everywhere he goes, he gets stopped for photographs, autographs, hugs, high-fives. In 2004, he moved from Seattle to Los Angeles to further his career and shortly thereafter he started another show, Eyes of Nye, in addition to hosting several television specials. In 2006, he nearly ended up married, but it didn’t work out. His fun-loving fianceé turned out to be, in his words, “less than stable.”

For many celebrities, it can be hard to separate the public persona from the private one. But in Nye’s case, science has always been more than a stage prop. Some of his earliest memories, he says, were of the wonders of his brother’s home chemistry set. Though he grew up in the Episcopal Church, he eventually drifted from it. At one point, he sat down and read the Bible all the way through, twice, taking notes and following the story with maps, only to arrive at the conclusion that people had pretty much made the whole thing up.

At Cornell University, Nye studied engineering. While there, he took Astronomy 102 with Carl Sagan and became one of the first members of The Planetary Society, which Sagan founded in 1980. Today Nye is CEO of the organization, the largest space-focused nonprofit in the world, and Sagan is often on his mind, mostly because his friend, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, recently rebooted Cosmos. He speaks with Tyson at least once a week, about wine and women and science and, lately, the show. When I called Tyson to ask about Nye’s newfound fight, he said it was in part an aspect of his role helming The Planetary Society. Nye has always had a public platform, he said, but now he was standing up for something bigger than the Science Guy, something that was true not only to him, but to all the scientists he represented.

While we waited for the dough to rise, Nye showed me around his home. Evidence of Bill, the engineer, was everywhere: a backlit map of the sun and Earth with a hacked on/off switch, a wall-mounted hook he’d made for his phone headset, a copy of Mechanical Engineering on the nightstand—he was proud that it had recently published his letter to the editor. Padding around in socks, Nye couldn’t take two steps before picking up a replica of the smallest steam engine ever made, pointing out a Nest smart thermostat, or showing off the energy-saving pump and sensor system under his sink. He is obsessed with his energy consumption; he installed solar panels over his garage several years ago.

That weekend, Nye had houseguests, Steve Wilson and his wife, Julie Lin. Like a lot of his friends from Seattle, they love swapping the cold drizzle of the Pacific Northwest for sunny Studio City. And, of course, it was Super Bowl Sunday and the Seahawks were playing. Everyone—Nye especially—was pumped. A week ago he’d installed a new TV for the sole purpose of watching the game in the living room (the den, he said, “didn’t have the big game vibe”). The neighbors were coming. He was making his grandmother’s onion dip and Bob Picardo’s pizza. Out on the porch, where we’d gone to talk, Nye interrupted our conversation every few moments, waving and shouting, “Go Seahawks!” at anyone who passed by.

Bill’s Loves: Dancing. A few nights a week, Nye goes out swing dancing. He was one of the most popular celebrities ever on Dancing with the Stars (until he tore his quadricep). He even patented a new kind of toe shoe for ballet.

As with his gadgets and his football team, Nye loves his yard. He pointed out a camphor tree and said it would start to smell like Vicks VapoRub in a few weeks when it bloomed. He then noted some tufts of feather grass and scraggly blue fescue sprouting beneath it. In the two-lane street in front of his house, Nye pointed out a white square: home plate. He’d painted it for summertime games with the local kids.

Just then Nye noticed a car barreling down his block. He leaned forward and bellowed, “Sloowdoooown!” He put his hands on his knees, all pointy-jointed and long-limbed. He looked like a figure from a Norman Rockwell painting, there on his porch, coffee cup in hand, rocking in his chair and defending his neighborhood.

Nye made a sweeping gesture and uttered another phrase he favors. “We would not have this”—he paused—“all this, without the body of knowledge of science.” He added, “And to have people suppress that, ignore that, it’s certainly their First Amendment right, but it’s not in our best interest. And I don’t just mean the people of Kentucky or America, I mean humanity.”

Nye abruptly asked if I wanted to go inside. It was getting cold, plus he had that dip and pizza to make. He dashed out to his backyard garden and pulled a few carrots from a bed, pointing out a new compost container he’d installed, bruising his thumb black in the process. As game time neared, the Wilsons returned from a drive, a few neighbors showed up, and everyone crowded into the living room. From the start, the Seahawks just killed. Nye whooped and hollered, high-fiving Steve and Julie and saying, again and again, “Oh, this is very, very satisfying.” The next morning, he rose, did his morning workout of 250 sit-ups and 150 push-ups, picked out a few bow ties among the hundreds hanging from his closet door, and caught a plane to Nashville for a quick stopover en route to the debate.

As Nye flew from Los Angeles to Tennessee, he passed over some of America’s fiercest battlegrounds for science education. In the past few years, a handful of charter school systems have sprung up in Texas, Arkansas, and Indiana that use textbooks that call evolution “an unproved theory” and explain that “supernatural intervention created the first cell.” Between them, the schools account for at least 17,000 students and $82.6 million in taxpayer funds. Scientific literacy among U.S. grade school students has flat-lined since at least 2003, according to a 2012 report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The same survey, conducted every three years, found that U.S. 15-year-olds consistently placed in the middle of a 65-nation pack—far behind superstars like China and Finland. The troubling trends are matched with increasingly harsh immigration policies that make it more difficult for foreigners to attend American universities and stay after graduation, and a concerted effort to deny the scientific validity of human-caused climate change. Nye speaks on all these topics, but it’s early science education that worries him most. A population with no foundation in basic science, he says, is a population of uninformed voters who face limited career prospects.

“I want to destroy him,” Nye said of Ham in the days leading up to the debate, “and I’m in a unique position to do so.”

Scientists seem powerless to stem this rising tide, and that’s largely because they fare so poorly at rebutting dubious ideas. “Scientists are trained to review an exhaustive list of literature and information, gather all the evidence, then cautiously make their way to reasonable, logical conclusions,” says Ginger Pinholster, the director of public programs at the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “The public wants to know the headlines, the punch line, and what’s in it for me. It flips the scientific communication process on its head.”

When creationists have lured scientists into debates, the result is usually unsatisfying. They unearth slide after slide of unfounded ideas and data with just enough of a whiff of truth to seem plausible. The scientists then spend most of the time arguing about the ideas on the various slides—in the process, giving them weight—rather than addressing the greater point: that the entire logic is flawed. Better to avoid debates altogether. Unless, of course, you’re Bill Nye. Back in California, he had told me, “I want to destroy him, and I’m in a unique position to do so.” By him he meant Ham. By his position, he meant that, while he may be the Science Guy, he’s not a scientist. He can engage, and so—damn it—he will.

Petersburg, Kentucky, lies within rifle shot of the Ohio River, which runs along the Ohio and Indiana border. Cincinnati is 20 minutes away. The hills here are low, rolling and Midwestern, the landscape exurban. Smokestacks from a coal plant across the Ohio River are the most prominent feature until, turning onto Bullittsburg Church Road, a gate with a stegosaurus appears. The grounds of the Creation Museum lie on the other side. At the entrance, folks were already lining up at 2:45 p.m. for the 7 p.m. debate.

Inside the museum, the atmosphere was hushed, almost solemn. The docents wore tight smiles as they directed guests. Many of the exhibits were extraordinary: dinosaurs (a velociraptor, a tyrannosaur) alongside a Who’s Who of Old Testament characters (Methuselah, Adam, Eve, Noah). Packs of visitors wandered the halls, and some—men, always—proselytized before congregations of three or four. Children kept close to their parents. In one grim hallway on the fall of man, a little girl clutched the folds of her mother’s floral-print dress.

Pre-debate, Ham politely refused to answer several questions from the press related to his proposed Ark Park, a full-scale replica of Noah’s Ark to be built on 800 rural acres 40 miles to the south. The estimated cost is $73 million, and Ham was raising money by issuing junk bonds. Ham said he wasn’t allowed to talk about the bonds but was happy to discuss the debate. When asked if Nye could say anything that might change his mind, he answered, “You know what? I’m a Christian, and I know God’s word is true, and there’s nothing he could say that will cast doubt on that.”

As guests filed into the auditorium, Nye’s face greeted them from a large screen. It was his old show—the episode on geology. Ham’s people had asked Nye to send some clips to play before the debate, so he’d chosen ones that would fly in the face of their beliefs. He was already competing.

The debate got underway. There were introductions, opening arguments, and 30-minute presentations from each man. Nye looked energetic in a suit and his signature bow tie. Two hours in, Ham asked Nye the reverse of what the press had asked him: What might change his mind? “We would need just one piece of evidence,” Nye said. “We would need the fossil that swam from one layer to another. We would need evidence that the universe was not expanding. We would need evidence that the stars appear to be far away but they’re not. We would need evidence that rock layers can form in just 4,000 years. We would need evidence that you can reset atomic clocks and keep neutrons from becoming protons. Bring on any of those things and you would change me immediately.”

Toward the end of the debate, the audience had a chance to ask questions of both men, and those directed to Nye seemed designed to trip him up. One asked: How did the atoms that created the big bang get there? “This is the Great Mystery!” Nye replied, shrugging his shoulders and raising his hands. “You’ve hit the nail on the head. What was before the Big Bang? This is what drives us. This is what we want to know. . . . To us, this is wonderful and charming and compelling. This is what makes us get up and go to work every day! To try to solve the mysteries of the universe!”

Ham smiled and said, calmly, “Bill, I just want to let you know that there’s actually a book out there that actually tells us where matter came from.” Much of the audience laughed in agreement. Nye stared intently at his opponent, holding his tongue, and that was about it. Ham’s strength came from his faith and his flock. Nye’s came from the mystery and wonder of the universe. As the audience shuffled out of the museum, they exited to find a howling winter storm. It was blizzarding and icing over mightily, and there was a traffic jam in the stegosaurus parking lot.

A day after the debate, the evangelical preacher Pat Robertson went on television to scold Ham. “Let’s be real, let’s not make a joke of ourselves,” he said. “We have skeletons of dinosaurs that go back about 65 million years. And to say it all came about in 6,000 years is just nonsense.”

Yet in the weeks that followed, the fallout continued. Ham announced the debate had helped his ministry raise tens of millions of dollars, and that he now had the $62 million required to break ground on the Ark Park. Nye fired back with an article in Skeptical Inquirer magazine that concluded: “We’ve already traveled a long way, but with projects like the Ark Park still in play, there is quite a journey yet ahead.”

Then, as if taking his own advice, Nye picked up and moved from Los Angeles to a New York City apartment with a view of the Empire State Building. He says he wants to position himself at the center of the media capital of the world, so he can walk to the national news channels. Recently, he debated climate change with an economist on CNN and joined John Oliver on Last Week Tonight for a spoof mocking false balance in climate-change reporting. He also completed a book, Undeniable: Evolution and the Science of Creation, which comes out this fall, and has started talks about a new show.

Bill’s Loves: Family. His mother was likely a codebreaker in World War II and his father was a traveling salesman, who in his earlier years played a banjo ukulele and billed himself as Ned Nye, boy scientist. His father also wrote a book on sundials.

But before any of that, Bill Nye woke up the morning after the debate and did something he will do, again and again and again, for the rest of his life: He went to school.

At 8 o’clock in the morning, a parent with his kids in the back of a minivan picked up Nye and drove him to the Schilling School for Gifted Children, just north of Cincinnati. Nye took the stage to a roar and began pacing. He looked loose: a stand-up doing crowd work, telling jokes that his longtime agent, Betsy Berg, who sat in the back row, has heard about a million times. Still, she cackled at each one. His voice, slightly raspy, grew stronger with the laughs and applause. Then kids came up onto the stage, one by one, with questions for the Science Guy. A seven-year-old girl in a penguin hat, Bell Page, asked about platypuses. It wasn’t a question, actually. She just loves platypuses. “Why are they mammals?” Nye asked her, drawing her in.

“Milk,” she replied softly.

“Yes! And why is it important that we know what’s what? Because there are two questions, really, that all of us have—are we alone in the universe, and where did we come from? By figuring out that these animals have these unusual characteristics, we figure out who came from where.”

A boy in a long blue T-shirt approached. Nye greeted him with: “The man in blue!”

The boy asked, “What was the biggest explosion, in all of your experience?”

“Great question!” Nye said. “Probably at a quarry, once, where we exploded a bunch of rock, but the scariest explosion, which is more important, came from a little piece of sodium dropped into water, which creates a huge reaction. You know sodium?”

“No.”

“You ever had salt?”

“Yeah.”

“So, salt is sodium . . . chloride,” he paused before the word, inviting an answer from the audience. Several kids leaned forward in their seats. “In pure form, both sodium and chloride are poisonous, but bonded together you can’t live without it.” He paused again before letting the punch line land. “It’s not magic, it’s . . .” And then everyone in the small auditorium on a cold, bright Midwestern morning shouted in unison, “Science!”

This article originally appeared in the September 2014 issue of Popular Science.