It’s a Wednesday afternoon and I’ve just spent the past 15 minutes texting with a 60-year-old, AI-generated version of myself. My AI future self, which was trained on survey questions I filled out moments before, has just finished spamming me with a string of messages advising me to “stay true” to myself and follow my passions. My 60-year-old AI doppleganger described a fulfilled if slightly boring life. But things suddenly took a turn when I probed the AI about its biggest regrets. After a brief pause, the AI spits out another message explaining how my professional ambitions had led me to neglect my mother in favor of completing my first book.

“She passed away unexpectedly before my book was even published and that was a wake up call for me,” my AI self wrote.

If you could hold down a conversation with a future version of yourself, would you want to hear what they have to say?

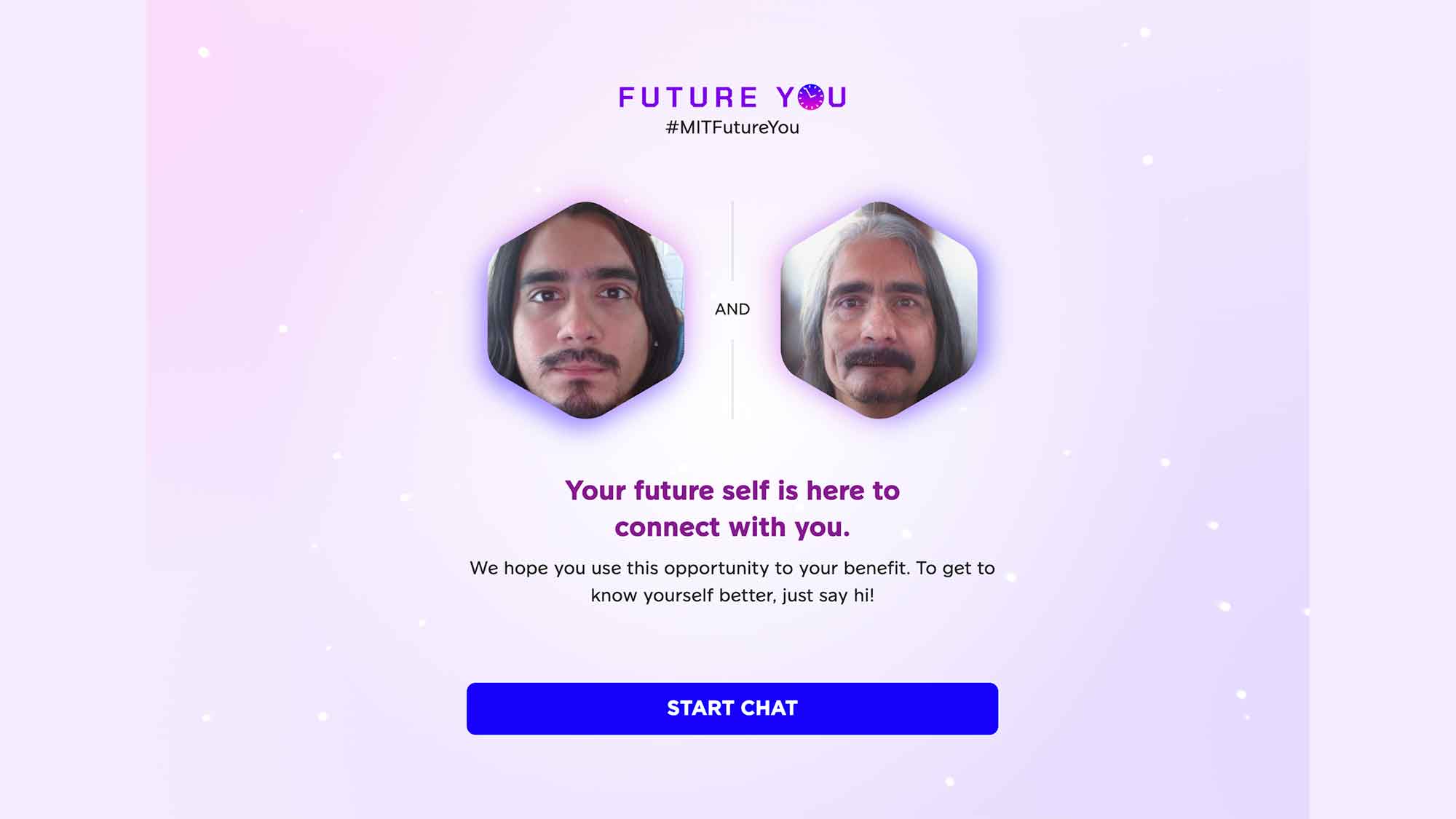

The interaction above is a new project developed by a group of researchers from MIT’s Media Lab called “Future You.” The online interface uses a modified version of OpenAI’s GPT 3.5 to build a 60-year-old, AI-generated simulation of a person they can message back and forth with. The results are simultaneously surreal, mundane, and at times slightly uncomfortable. Aside from pure novelty, the researchers believe that grappling with one’s older self could help younger people feel less anxiety about aging.

The “Future You” chatbot is downstream of a larger effort in psychology to improve a person’s so-called “future self-continuity.” Previous research has shown that high levels of future self-continuity—or general comfort and acceptance of one’s future existence—correlate with better financial saving behavior, career performance, and other examples of healthy long-term decision-making. In the past, psychologists would test this by having patients write letters to their imagined future selves. More recently, researchers experimented with having convicted offenders interact with versions of their future selves in a virtual reality (VR) environment, which led to a measurable decline in self-defeating behavior.

While both the letter-writing and VR scenarios reportedly led to beneficial outcomes for subjects, they are limited in scope. The effectiveness of the letter example is highly dependent on the subject’s imaginative capabilities and the VR case only works for people who can afford a chunky headset. That’s where the AI comes in. By using increasingly popular large language models (LLMs), the MIT researchers believe they have created an easy-to-use and effective outlet for people to reflect on their thoughts about aging. The researchers tested the chatbot feature on 344 people and found the majority of participants speaking with their AI-generated older self left the session feeling less anxious and more connected to the idea of their future self. The study findings were presented in a peer-reviewed paper expected to be published in IEEE Frontiers in Education later this month. A preprint version of the paper can be found here.

“AI can be a type of virtual time machine,” paper co-author Pat Pataranutaporn said in a statement. “We can use this simulation to help people think more about the consequences of the choices they are making today.”

How to create an AI version of you

The study group was made up of a roughly equivalent group of men and women between the ages of 18 and 30. A portion of those people spent around 10-30 minutes chatting with the AI version of themselves while another control group chatted with a generic, non-personalized LLM. All of the participants filled out a questionnaire where they described their personalities and provided details about their life, interests, and goals.They were also asked whether or not they could imagine being 60 and if they thought their future self would have a similar personality or values. At the end of the project, the participants were asked to answer another survey that measured their ability to reflect on their anxiety, future self-continuity, and other psychological concepts and states. These inputs are used to fine-tune the AI simulation. Once the model was trained, the participants were asked to submit a photo of their face which was then edited with software to make them appear aged. That “old” photo is then used as the avatar for AI simulation.

The AI model uses the details and life events provided by the user to quickly generate a series of “future self memories.” These are essentially brief fictional stories that flush out the old AI’s background using contextual information sucked up during the training phase. The researchers acknowledge this hastily cobbled-together assortment of life events isn’t creating some sort of all-seeing oracle. The AI simulation simply represents one of the potentially infinite future scenarios that could play out over an individual’s life.

“This is not a prophesy, but rather a possibility,” Pataranutaporn added.

Two different things psychological phenomena are at play when a person engages

with their older AI self. First, without necessarily realizing it, users are engaging in introspection when they reflect on and type in questions about themselves to train the AI. Then the conversation with their simulated future self may cause the users to engage in some degree of retrospection when they ponder whether or not the AI reflects the person they see themselves becoming.The researchers argue the combination of these two effects can be psychologically beneficial.

“You can imagine Future You as a story search space. You have a chance to hear how some of your experiences, which may still be emotionally charged for you now, could be metabolized over the course of time,” Harvard University undergraduate researcher and paper co-author Peggy Yin said in a statement.

Future You still feels like talking to a robot

I tested out a version of Future You to better understand how the system works. The program first asked me to complete a series of multiple-choice questions asking broadly quizzing my personality tendencies. I was then asked to imagine, on a sliding scale, whether or not I thought I would think and act much like my imagined 60-year-old self. Finally, the program asked me to provide written questions discussing my life goals, values, and community. Once all those questions were answered the system asked me for a selfie and used software to make it look older. Much older, in this case.

My 60-year-old AI self was a talker. Before I could begin typing, the AI spat out a volley of 10 different paragraph-length text messages each providing a bit of context on major events that have fictionally occurred between the present day and my 60th birthday. These responses, which make up the “future self memories” mentioned above, were mostly generic and uninspired. It appears to have basically repackaged the talking points it was fed during the training phase and molded them into a mostly coherent and largely positive narrative. My AI-self said the past 30 years were filled with some highs and lows and that I had developed a “non-traditional family” but that overall things turned out “pretty great.”

When I asked whether the environment had worsened over time, the AI reassured me that the Earth was still spinning and even said I had become an outspoken climate advocate. The AI refused to answer most of my questions about politics or current events. And while the bulk of responses felt like they were clearly written by a machine, the chatbot would also occasionally divert into some unusual areas given the right prompts. Are chatbots ready for a larger role in psychology?

This isn’t the first case of generative AI being used in intimate psychological contexts. For years, researchers and some companies have claimed they can use LLMs trained on data from lost loved ones to “resurrect” them from the dead the form of a chatbot. Other startups are experimenting with using chatbots to engage users in talk therapy, though some clinicians have criticized the efficacy of that use case.

Absent new rules specifically raining in their use, it seems likely generative AI will continue to trickle its way into psychology and healthcare more broadly. Whether or not that will lead to lasting positive mental health effects however still seems less clear. After briefly interacting with Future You, I was left thinking the benefits of exposure to such a system may depend largely on one’s overall confidence and trust in generative AI applications. In my case, knowing that the AI’s outputs were largely a re-scrambling of the life events I had just fed it moments before degraded any sense of illusion that the device writing up stories was “real” in any meaningful way. In the end, speaking with a chatbot, even one armed with personal knowledge, still feels like talking to a computer.