Even if you had free run of any skybox in Madison Square Garden, you still wouldn’t see half the action that you will in your own living room, one day soon, on a large-screen holographic television. Without ever leaving your chair, you’ll be poised to watch each play unfold from whatever perspective you choose, gazing into the depths of your TV. The only thing lacking will be the soggy cheese fries.

Although this scenario is a decade away, a small-scale version exists today in the Dallas laboratory of Harold Garner, a tireless 51-year-old medical doctor, plasma physicist and biochemist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The prototype he built is the first machine ever to generate holographic movies–true 3-D without special glasses or nausea.

How did a guy who works in a medical center discover the key to depicting holographic objects in motion? Garner’s chair in developmental biology at UT is endowed in part by the founders of Texas Instruments, and the company gave him early access to a digital micromirror device (DMD) that is now used in high-end video projectors. It is made up of nearly a million reflective panels, each of which can be angled by a computer several thousand times per second to reflect or deflect beams of light, producing moving pictures. Garner’s big idea was to blast the DMD with a laser rather than with a typical projection bulb. He programmed the DMD to reflect a sequence of

2-D interference patterns (called interferograms) that disrupt the laser light in such a way that it reflects a 3-D hologram.

Garner’s biggest challenge has been to find a suitable screen. To unfold the 2-D interference patterns into true 3-D images, the projection surface must have volume. A column of mist will work, as will a tub of Jell-O, but both diffuse the projected image, marring sharpness. So Garner is working with a display composed of layers of microthin LCD panels, each of which can, when electrically charged, be made clear or opaque. When the panels flash on and off in quick succession to assemble the hologram, the speed is more than sufficient to convince the eye that it’s seeing a solid object.

Such displays exist today, but they work without the benefit of holography; instead they have to slice up a 3-D image and send it sliver by sliver to the LCD screens. The picture is almost the same as Garner’s would be, but this method requires far greater processing power, because you need the x, y and z coordinates for every slice. This is why Garner’s approach is the most viable solution for 3-D TV. “We’re sending the 3-D images as a 2-D interferogram,” Garner says, pointing out that this doesn’t require any more bandwidth than today’s television signals, “so we can use the current broadcast infrastructure.” As for creating holographic content, it would have to be recorded with a series of cameras shooting from different viewpoints.

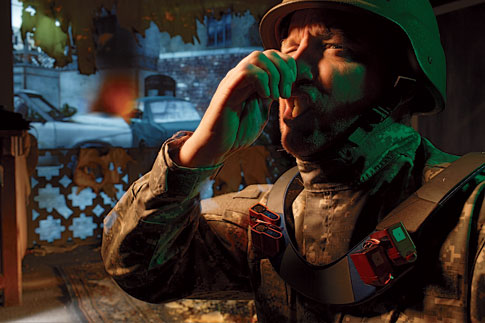

The first application of Garner’s technology may be in the holographic imaging of MRIs or in head-up displays for the military (he’s had discussions with the U.S. Air Force and Lockheed Martin), so it’ll be a while before this TV makes it to Circuit City. Still, it may well happen before the Knicks win the NBA title again.

The Road to 3-D TV

1947

While working for the Thomson-Houston Electric Company in Rugby,

England, Hungarian physicist Dennis Gabor invents the hologram, for which

he is awarded the Nobel Prize in 1971.

1987

TI engineer Larry Hornbeck invents the digital micromirror device, an optical semiconductor used in video projectors and TVs starting in 1996.

2003

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center researcher Harold Garner demonstrates the first holographic video-projection system, screening hazy red images of a helicopter circling a jet.

2008

The U.S. Air Force installs holographic head-up displays in fighter jets, bringing aviators 3-D images

of battlespace positions.

2015

Holographic TV goes live with a pay-per-view satellite broadcast of the heavyweight boxing championship.