The weirdest thing we learned this week: werewolf tomatoes and overdosing on placebos with Wendy Zukerman

The host of Science Vs joins us for a round of some truly bizarre facts.

What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits iTunes, Anchor, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show. And don’t forget to snag tickets to our next NYC live show on June 14.

This week’s episode features an extra weird, very special guest: Wendy Zukerman, host of the Science Vs podcast. Take a listen below (or wherever you like to get your podcasts) and keep scrolling for more info on some of the stories we shared. And don’t forget to take a listen to Wendy’s full Science Vs episode on the placebo effect.

Fact: Tomatoes took a long time to take off in the U.S. because of werewolves

By Rachel Feltman

A few weeks ago I was reading a book and came across a brief, throwaway reference to the long period during which Americans were afraid of tomatoes. I’d heard this before, but decided it was worth investigating further. As it turns out, a lot of the lore around colonial fear of tomatoes is probably made up. But that doesn’t mean tomatoes didn’t have a dicey entry into American cuisine.

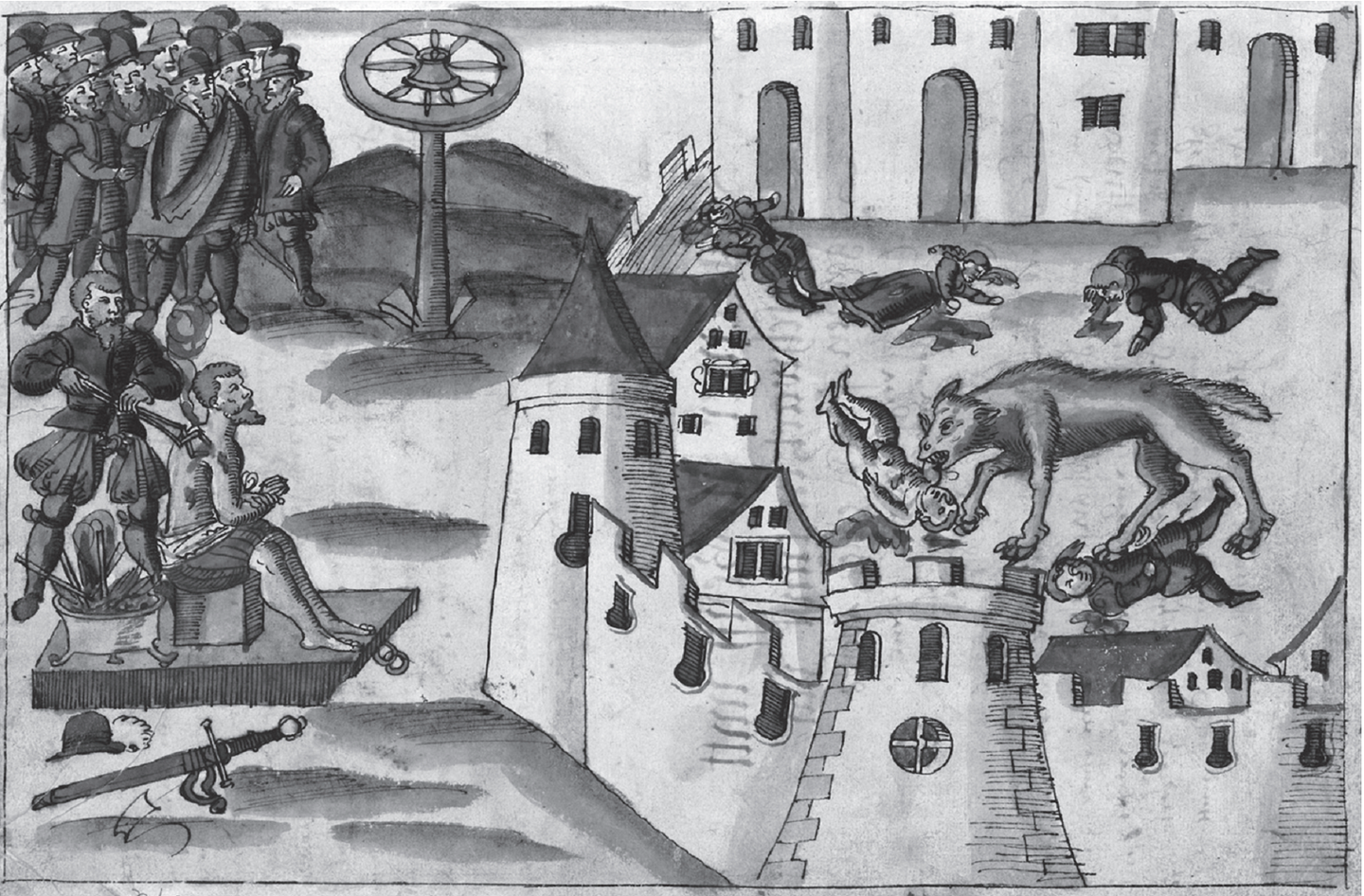

Let’s start with the reasonable stuff: tomatoes are in the nightshade family, which means they’re related to—and bear some resemblance to—belladona and mandrakes. Both of these plants produce compounds that are decidedly not great for you (though that hasn’t stopped humans from putting their essence on their eyeballs). British cultivators wrote that the plant was probably poisonous, or at least not good for you, due to its family legacy. This is a fair concern to have about a previously unknown fruit.

But 15th-century Spanish cooks had quickly adopted the fruit after seeing it used in colonies in its native South America, and Italian chefs picked up on the trend after a delay that mostly had to do with hygienic fears (tomatoes, hanging low to the ground, seemed by nature to be suspiciously dirty to aristocrats). British people knew this. They knew people in Spain and Italy were enjoying plump tomatoes without dropping dead. This cognitive disconnect has inspired the description of a phenomenon called the tomato effect: when someone can see that something is working, but believes it’s ineffective because reality conflicts with their current understanding of how the problem works.

Now for the even less reasonable stuff: another reason the distrust of tomatoes persisted in the American colonies is their association with witchcraft and the occult. I won’t spoil the rest: check out this week’s episode to hear more.

Fact: You can pop your neck and cause a stroke (but you probably won’t)

By Eleanor Cummins

It seems to happen all the time: Someone innocently cracks their neck, only to realize they’ve had a stroke.

But I pop my neck a lot, and have no plans to stop, so I wanted to know what the risks really were.

When you pop a joint, what you’re hearing is tiny bubbles of air forming and rapidly collapsing in the fluid between those joins. It seems fairly innocuous, because in most cases it is. Doctors are confident it doesn’t cause arthritis in your knuckles, despite what your grandma says. But your neck is a much more sensitive area.

It turns out that manipulating your neck in any way puts you at an increased risk of stroke or ischemic attack. And “manipulation” can range from something as small as turning your head one day to look for oncoming cars to allowing your chiropractor to just let it rip. What happens is, the artery at the back of your neck rips open. When your artery tries to heal itself, it will form blood clots, which can dislodge and wind up in your brain, causing a stroke.

But the risk is super small. The odds of experiencing an arterial tear from any source are about 1 in 100,000. The odds of a simple pop of the neck causing this are probably even smaller, though we can’t say for sure. Because that’s the most important part of this: All the information we have, and it’s minimal, is merely correlational. It’s possible, for example, that chiropractors aren’t causing strokes by popping patients’ necks, but rather popping the necks of patients who came in because they were already stroking, and thought the chiropractor might be able to fix their headache.

It’s probably a good idea to cool it with the neck popping when possible. Chiropractors themselves are changing the way they pop, to reduce pressure on the neck. But next time you see this strange phenomenon in the news, I just want my fellow poppers to know there’s no immediate reason to freak out.