This Device Reads Your Mind Through Your Veins

And it's the size of a matchstick

In recent years, scientists have been developing new and creative ways to put electronics in the brain. These devices are useful for paralyzed patients to control prosthetic limbs with their minds, to help locked-in patients communicate with the outside world, or to help researchers better predict seizures in epileptic patients. But implanting them requires opening the skull, an intrusive procedure. Now researchers from the University of Melbourne have created a device that can be inserted into the brain through the blood vessels, no invasive surgery required. The study was published this week in Nature Biotechnology.

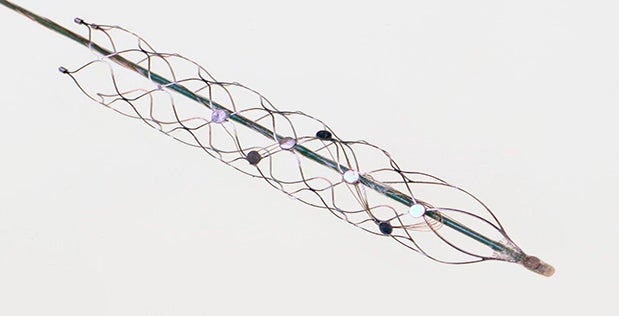

The device, about an inch long, looks similar to a stent, an apparatus placed around the heart to open up clogged blood vessels—in fact, the researchers named it a “stentrode.” To insert it, the researchers put a catheter into a vein in the neck, then snake it through the blood vessels into the head until the end is in the desired part of the brain, next to the motor cortex. Once the catheter reaches the right spot, the stentrode sticks to the sides of the blood vessel, where it can collect data from the activity of neurons nearby. The data reaches the researchers’ computers through a wire that comes out of the neck.

When the researchers tested the device on sheep, they found that the stentrodes were sensitive and transmitted good data. They also stayed in the sheep for 190 days without issue, indicating to the researchers that the devices could stay in humans for a long time without issue.

The stentrode, and similar devices that can be implanted in the brain without opening the skull, might even be useful beyond a medical capacity, becoming commonplace and changing the way we interact with computers. Of course, the necessity of a wire coming out of a user’s neck is less than ideal, so these devices might first have to become wireless if they’re going to become widespread among the population.

The researchers hope to test the stentrode in humans next year.