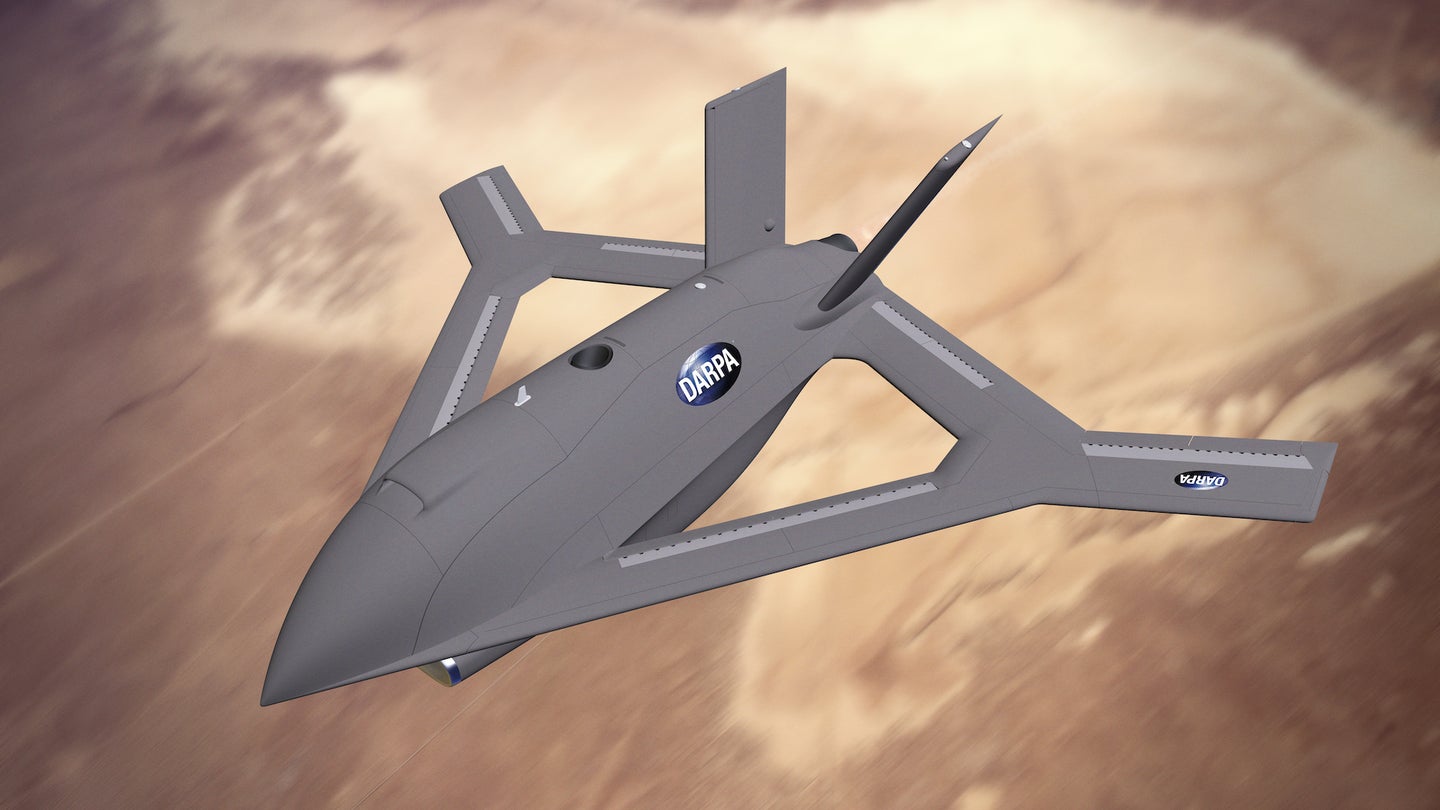

DARPA wants aircraft that can maneuver with a radically different method

The Pentagon's R&D wing is taking the next steps toward developing airplanes that don't use traditional control surfaces like ailerons.

On January 17, DARPA announced the next steps of a program to create an aircraft designed to fly entirely on control surfaces that lack the moving parts that airplanes typically use to maneuver. DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, specializes in blue-sky visions, investing in research towards creating new possibilities for technology. In this program, it seeks to change how aircraft alter direction in the sky.

The program is called Control of Revolutionary Aircraft with Novel Effectors, or CRANE. DARPA first started the program in 2019, with a request for proposals to “design, build, and flight test a new and novel aircraft that incorporates Active Flow Control (AFC) technologies as a primary design consideration.”

AFC is a kind of control paradigm that replaces moving parts like ailerons and rudder of an aircraft. Planes change their positions by redirecting airflow with ailerons attached to the wings, an elevator at the tail, and a rudder. These controls are what let planes roll side to side, pitch upwards to take off and downwards to land, as well as or yaw left to right. Extendable slats and flaps on wings can also allow planes to generate more lift at low speeds, and to slow the plane as it angles down for a landing. (Here’s more on exactly how wings generate lift.)

With “Active Flow Control,” aircraft can use plasma actuators or synthetic jet actuators to move air, instead of relying on physical surfaces. With plasma actuators, this is achieved through changing the electrical charge of air passing over the actuators mounted in the wing, in turn changing the flow of that air. Meanwhile, synthetic jets can inject air into the airflow over the wing, changing lift. In 2019, NASA patented a wing control system that combined both plasma and synthetic jet actuators, with the goal of creating actuators without any moving parts, and which were “essentially maintenance free.”

In DARPA’s 2019 call for proposals, it emphasized that this technology could lead to “elimination of moving control surfaces for stability & control,” improvements in “takeoff and landing performance, high lift flight, thick airfoil efficiency, and enhanced high altitude performance.”

With improved takeoffs and landing, such a control system could allow for “extreme short takeoff and landing” (ESTOL), where a plane or drone operates from runways even smaller than those present used for short takeoff and landing. The Department of Defense and NATO define short takeoff as being able to land on a runway 1,500 feet long, with a 50-foot obstacle at either end.

Because these new flow controls could increase the angle of lift for takeoff and improved braking for descent, it’s possible that a plane with it could land in an even smaller area. That expands how and where such planes can operate, and matters especially with future wars and operations at sea, where the military has to bring its own runways on ships, or on small islands.

Another area where these controls can help is in making it harder for aircraft to be observed, as it reduces the number of surfaces on an aircraft that would reflect radar signals. The controls can also be quieter, minimizing detection from audio sensors, and can improve aircraft stability and lift at high altitudes. The controls also allow for thicker plane wings, which can hold more fuel.

In December, Aurora Flight Sciences (which is a part of Boeing) was awarded over $89 million for the CRANE program, or roughly the cost of a single F-35A stealth jet fighter. In Phase 1, which is already completed, Aurora created an aircraft that was able to use active flow control to demonstrate control in a wind tunnel test. Phase 2, which was announced this month, will focus on designing and developing the software and controls of an X-plane demonstrator that “can fly without traditional moving flight controls on the exterior of the wings and tail.”

Should DARPA decide to continue the contrast, there’s the option for Phase 3, in which DARPA will fly a 7,000 pound X-plane that incorporates active flow control and relies on it for controlled flight.

In starting the design from a new kind of control paradigm, DARPA hopes to spark new thinking about how planes can fly and maneuver. DARPA’s long record of X-plane design includes everything from long endurance drones to stealth aircraft to hypersonic designs, all of which have led to changes in military design and planning. The ability of aircraft to use active flow control to operate from smaller runways expands not just the areas where the military can fight, but even the size of ships that could launch long-flying drones.

DARPA, on the innovation edge of research, has focused the project on making sure the technology can work in demonstration, first. Should it prove successful, it will be up to other parts of the military to best determine how they want to employ it.

Correction on Jan. 31, 2023: This article was updated to change “1,5000 feet long” to “1,500 feet long” and “active follow control” to “active flow control.”