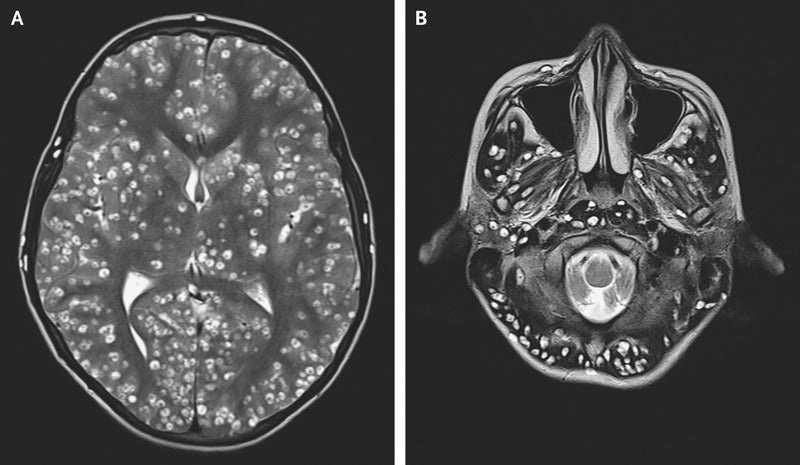

See what happens when tapeworms infest your brain

A tragic case report shows the horrifying result when tapeworms don't stay confined to your intestines.

Tapeworms are revolting no matter where you find them. But when they are in your gut, at least the parasites are in their natural habitat. We are, unfortunately, their primary hosts and, as parasites, their job is to colonize our intestines, shed eggs out our bums, and infect other animals.

Normally, they perform this job relatively quietly. They eat your food and hang out inside your guts, but they don’t generally want to kill you. That’d reduce their number of potential homes. That’s why many people infected with tapeworms stay fairly symptom-free (we regret to inform you that often folks realize they’re infected when bits of the worms start coming out in their poop). In the rare event the intestinal infection does cause symptoms, they usually include loss of appetite, weight loss, an upset stomach, and perhaps abdominal pain.

But that’s all assuming they stay in your gut.

As one tragic case report in the New England Journal of Medicine this week shows, that’s not always what happens. Tapeworms can get into other parts of your body and cause much more severe symptoms. A teenager in India who had been infected with tapeworms died as a result of numerous cysts—formed by the tapeworms—in his brain (he had them throughout his body as well), which doctors only found when he showed up at the emergency room in Faridabad with generalized tonic-clonic seizures. These full-brain seizures, plus his groin pain, eye swelling, and general confusion are fairly common symptoms for bodily infection with tapeworms.

It is possible for tapeworms to migrate out of human intestines, according to the Mayo Clinic, but this kind of full-body infection results from a different disease pathway and is far more common in another animal: pigs.

The kind of tapeworm infection an animal gets largely depends on which stage of life the worm is in when you ingest the parasite. Tapeworms, specifically the species Taenia solium, have a life cycle that depends on both humans and pigs (there’s also a beef tapeworm, but it doesn’t cause bodily cysts). T. solium begins life as an egg inside a human, though it quickly departs out the anus. Pigs who consume either feces or infected water also ingest the eggs. Those eggs travel to the pig’s guts, where they hatch, burrow through the intestinal wall, and migrate to the farm animal’s muscles and organs. There they become cysts. This kind of infection is known as cysticercosis, which is different from what we’d call “having tapeworms” the way most people get them.

Humans usually become infected because they eat undercooked pork with infective cysts, thus leaving the worms (called cysticerci) alive. The cysticerci travel to our guts, where they mature into adult tapeworms roughly 10 feet long, which in turn lay eggs and start the whole process over.

Technically, though, as this case study proves, if a human eats the tapeworm eggs, we can get cysts just like pigs. That’s what happened to this poor boy—he must’ve eaten the eggs at some point, gotten infected, and not realized until his body was riddled with cysts. (And please note, you can’t get these cyst just from eating undercooked pork.)

The specific form of the disease this boy had, neurocysticercosis, is very rare in developed nations because farms in those areas have hygiene standards intended to avoid any potential contamination of both pigs and humans. Unfortunately, that doesn’t make it rare worldwide. The World Health Organization estimates that roughly 2.5 to 8.3 million people suffer from neurocysticercosis every year, mostly in developing parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Subsistence farmers there don’t have access to the same resources to prevent disease, and thus infections are far more common.

If you’re reading this in a country like the U.S., though, you’re highly unlikely to ever even be exposed to tapeworm eggs unless you travel internationally. Consider yourself lucky.