DNA tests can’t tell you your race

Many people turn to companies like 23andMe to learn about ancestry and ethnicity. But the genetic connection is far more complicated than the industry lets on.

It’s always a mess when Latinx folks take DNA tests. Things go alright, until we get to the “ancestry” portion, which some commercial genetic tests label as “ethnicity.”

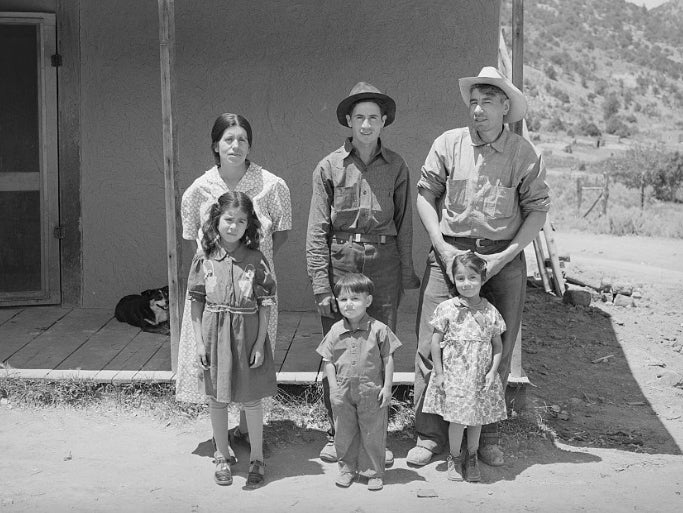

People who identify as Latinx claim ancestry from all over: indigenous Americans, Spanish colonists, enslaved Africans, Middle Eastern people, miscellaneous Europeans, and even Asians.

This can lead to unexpected DNA results. My grandfather is Mexican, but fair-haired and blue-eyed (we sometimes call people who look like him bolillo, which means “white bread”). When he got his report back from FamilyTreeDNA, he found out he had more North American ancestry than expected. Abuelo made some weird comments—but my friend’s brother’s reaction was much worse. Also Mexican, he came into the living room with his tests results printed out. “I found I’m 3 percent black,” he said. “What’s up my n*****s?”

Thankfully, his family quickly corrected him: “You just can’t say that word!” But to correct him more fully, they would need to let him know that a DNA test, no matter how sophisticated, can’t tell him what his race is.

Abuelo and my friend’s brother aren’t alone in their confusion. In the past few years at-home genetic testing has grown into a billion-dollar industry; since 2013, more than 26 million people have sent in their DNA for analysis. And while companies like 23&Me, AncestryDNA, and MyHeritage claim to be able to tell your “ethnicity”—a word they know many people will read as a synonym for “race”—none of them explicitly offer to tell consumers their racial make-up. There’s one simple reason for that: The science just doesn’t exist.

To understand this, let’s go back to my friend’s brother. He thought the test told him he was “3 percent black,” when in fact it reported that he had a 3 percent chance of having genetic ancestry from some part of the African continent.

How’s that different than being “3 percent black”? First off, that percentage is being interpreted incorrectly. A lot of people read their DNA tests like a pie chart: You’re 25 percent this or 50 percent that. But that’s not at all what the statistics represent.

“They are fractions, estimates. It’s saying that your genome has a certain percent estimate of representing a certain area,” says Marcus Feldman, a professor of biological sciences at Stanford University and director of the Morrison Institute for Population and Resource Studies.

Feldman explains that when it comes to people’s roots, the tests are saying something more like: We’re 30 percent confident that your DNA indicates ancestry from Okinawa, Japan. That’s not the same thing as saying someone is 30 percent Okinawan.

The vast majority of human DNA—we’re talking 99.9 percent—is entirely identical between individuals. So when the code diverges between two people, that’s interesting to scientists. A DNA ancestry test scans the entirety of your genome looking for single-letter differences. Statistical experts like Feldman have figured out that people from the same continent, on average, tend to have certain variations in the same regions of DNA. Still, it’s impossible to say that one tiny nuance comes from a specific place; analysts can only note when someone’s differences overlap a lot with a general geographic group.

“You can’t take your DNA and chop it up and say, ‘This bit came from here, and that bit came from there,’ ” Feldman says, laughing.

Feldman knows what he’s talking about: He was a part of the Human Genome Diversity Project, the first research group that sought out connections between genetics and geographic ancestry. Starting in the 1990s, collaborators began using blood samples collected from around the world to try to understand human migration and evolution. The result was the first-ever “map” detailing commonalities in the DNA of people from different regions. It was a monumental achievement: The Project’s results are still the baseline for most consumer tests on the market today.

Back to Feldman’s point about divvying up DNA … you might think your ancestry works sort of like inheriting genes from your parents—an even 50/50 split. But that’s not the case when you go back another generation, as DNA reshuffles and reorganizes with every new transfer. So even if your mom gave you 50 percent of her own genes, doesn’t mean you got an even portion of, say, her Pakistani parent’s. In fact, if you dig far enough, it’s possible you’ll find a direct ancestor that you have no genes in common with.

This means that you and your sibling can have significantly different ancestry results, given you’ve each inherited different portions of your parents’ DNA (unless you’re identical twins).

That brings us to another important detail: the fact that ancestry and physical appearance (or phenotypic traits) don’t directly overlap. Characteristics like skin color, hair texture, and eye shape are controlled by thousands of different genes—separate from the ones scientists look at when composing an ancestry profile. As a result, someone with a high estimate of West African ancestry might not look or even identify as black. Similarly, an individual whose tests come back with a very low estimate of West African ancestry might actually be black.

That’s why geneticists haven’t devised a test that can conclusively determine a person’s race. And in a way, it’s impossible. Race is about how we identify and are identified; it’s more than a question of appearance—it’s a question of culture, history, geography, and family. It can’t be boiled down to genetics and percentages.

“It’s fundamentally flawed to think that a genetic test can figure out race,” says Sarah Tishkoff, a professor of genetics and biology at the University of Pennsylvania. “The biggest issue is distinguishing between ancestry and race. Race is a socially constructed concept. How someone self-identifies in terms of their ethnicity or race may be different than what their genetic ancestry tells us.”

In fact, our concept of race has such little biological grounding that the Human Genome Diversity Project has opted to avoid using the word entirely.

“In our first papers on this, we never used the word ‘race.’ We used the term ‘ancestry,’ ” Feldman says. “Where is the continental ancestry? I still maintain that this is the only way to introduce anything biological or genetic into that discussion.”

Think about it in terms of science and history. European colonizers invented the concept of race 500 years before the double helix was discovered. Many of their terms for describing human difference, based on traits like skin color and facial features, are still used in our censuses and societies today. (For instance, our idea that a person can be “one-fourth” something comes from the logic Europeans used to figure out which mixed-race people were “black enough” to enslave.) This category-forming was not a scientific process—it wasn’t Mendel in a greenhouse with his peas. It was backed by men with giant armies, whose objectives were mass enslavement, conquest, and subjugation.

“I think in that period when Europe was dominant, [racial terms] were a way of classifying levels of inferiority,” Feldman says, speaking of the birth of white supremacy. “It was a validation of colonialism.”

This is what some people mean when they say race isn’t real: It’s a social concept created to empower Europeans, as much as it was created to describe differences between people. That’s why modern historians and geneticists worry about how people are trying to use DNA to define race .

“We think that when people use racial classifications when talking about genetic data, it may reify the wrong idea that there’s a biological basis to racial classification,” Tiskoff says.

In an ironic twist, however, race—and racism—have affected how we understand ancestry. DNA tests like 23andMe pack a strong Eurocentric bias because they’re based on genetic research that’s largely from one continent. In fact, the original samples analyzed by the Human Genome Diversity Project didn’t include any samples from North America.

While efforts have been made to produce more geographically representative samples, at-home DNA tests still give far more detailed answers about European ancestry than most other parts of the world. My grandpa’s tests, for instance, included incredible granular detail on his profile from the Iberian peninsula (it went so far as to suss Sephardic Jews from other Spaniards). But his American ancestry just said “North America” (a category that lumps Inuits together with Aztecs).

All this leaves us with the question of how we should talk about race as genetic analysis becomes more commercialized and common. The results, no matter how personal, can have serious social ramifications. There are websites that offer advice to white people on using DNA testing to apply for “minority status” in college admission. That cynical use of biological data should make us deeply uncomfortable—and it should make us think further about the information that helps us define our own identities.

The history you glean from a DNA test comes from context that biology can’t provide. It’s your choice to seek out that context, draw the lines to ancestors and colonial legacies, and determine who you are today.