12 months of pandemic life in 12 photographs

Some scenes can just never be separated from COVID-19.

Click here to see all of PopSci’s COVID-19 coverage.

There are certain sights that people have grown habituated—and even numb—to in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. We may have forgotten what it’s like to read someone’s facial expressions now that we’re always masked up in public. And we’ve probably grown accustomed to sanitizer dispensers greeting us in every school, store, and office.

Point is, the status quo has changed dramatically from last March to this March. Even if life slips back to normal with vaccinations, some scenes and symbols will always be inseparable from this global health disaster we’ve been fighting. Let’s take a look at 12 from around the US.

The extra-long swab used in early COVID-19 tests became somewhat of a meme in the first months of the pandemic. People described a tickling sensation in their brain, or even a stabbing pain, after getting brushed by a health care worker. But the intimidating length of the swab was important: Because the virus attacked the respiratory system, it could leave an imprint anywhere between the nasal passage and the back of the throat. Today, most tests use a simple saliva strip to collect a cell sample, albeit with weaker results.

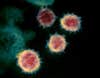

Most folks are familiar with the pom-pom-like illustration of the coronavirus shared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But what does the pathogen look like in real life? Epidemiologists at the National Institute of Health took microscopic scans of Sars-CoV-2 in action to see just how the spike proteins on its surface infiltrate and bind to cells in various human organs. The colorized results helped boost public knowledge about how viruses form, operate, and ultimately, mutate.

The phrase “deep clean” took on a new meaning in the pandemic, especially in the early months, when there was little understanding of how the virus was transmitted. Municipal workers and custodial staff used disinfectant wipes, sanitizing sprays, and even UV lights to prep mass transit and other public spaces for reopening. Not everyone had the same kind of personal protective equipment as specialized hazmat teams: Last April, New York City reported dozens of COVID-19 deaths among janitors.

The 2020 wildfire season didn’t stop for COVID-19. In fact, it burned harder than ever in California, with two giant blazes blanketing the counties around the Bay Area. Fires in the southern half of the state, plus Washington and Oregon, lasted through much of summer and fall, creating heavy plumes of smoke that could be seen all the way from space. The particles also blew east, resulting in smoggy, scarlet sunsets over the Midwest and Northeast.

While the slate of COVID-19 symptoms is long and mysterious, many patients seem to come down with pneumonia or worse, go into respiratory failure. Studies on some of these deadly cases show that the virus makes a beeline for lung tissue, causing the cells to grow, inflame, and even clot. Now, patients hospitalized for the virus automatically get a CT scan as part of their diagnostic test. Medical researchers in Canada and elsewhere are also using artificial intelligence to detect more subtle signs of disease in the lungs.

After an initial hiatus last spring, the NBA and WNBA took a dramatic approach to make sports happen again. Both leagues set up isolated player-only facilities in Florida where all training, games, and rest would take place. To bring fans in on the action, the NBA adapted Microsoft Teams’ video chat software to 17-foot-high digital screens, giving the appearance that there were raucous people in the stands. Other leagues settled for cutouts and streamed-in sounds until they could open their stadiums and arenas for real.

A year into the pandemic, school reopening continues to be a hot-button issue across the country. Some districts have chosen to stay completely online, while others have tested hybrid learning where kids rotate through classrooms and at-home lessons. College campuses small and large did the same, drawing on deep resources to mandate testing in dorms and among staff. For schools that did let students return to their lockers and desks, however, there were some common precautions: masks, physical barriers, and ventilation to help keep infection rates across the community low.

It took Anthony Fauci 52 years to become a household American name. He’s been working for the National Institute of Health since 1968, and became the director of the allergy and infectious diseases division in 1984. That role catapulted him to the front of the country’s COVID-19 response last year, even as other government entities tried to suppress and alter science-backed recommendations. Fauci continues to help lead the Biden administration’s coronavirus task force.

Last May the US passed the 100,000 death mark for COVID-19. Then in September, 200,000. In December, 300,000. The mortality rate picked up so quickly that by the presidential inauguration this January, the count had pushed beyond 400,000. The 500,000 mark came soon after on February 23, 2021. It’s the highest number of lives lost of any country in the world.

It took the world a while to catch on to wearing a mask every day last spring, due to questions around how effective they could be at blocking out SARS-CoV-2. But we now know that there’s a hierarchy: KN95, cloth, and then surgical. Still, disposable face coverings are cheap to buy and easy to distribute, and now they’re piling up as litter and trash. The impacts of the extra plastic have yet to be measured, but environmentalists are already seeing the telltale blue swatches wash up on beaches everywhere.

With jobs, schools, and community services shuttered, the US hunger crisis hit a drastic peak in 2020. Estimates from Feeding America hold that at least 50 million adults and children struggled to secure three square meals a day during the pandemic, all while farmers had to dump their overflowing stores. The impacts of this have been seen at donor-supplied pantries across the nation. The San Antonio Food Bank, for instance, has had nearly twice as many people lining up at its doors each day since COVID-19 started to spread.

Amid social distancing and coronavirus concerns, protesters around the globe found secure ways to demonstrate their First Amendment right in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. But in many places, police showed out in full force as well, often equipped with riot gear and crowd control weapons. Epidemiologists and physicians fretted that the rampant use of tear gas would damage people’s lungs and make them more vulnerable to long-term COVID-19 symptoms.