Sea turtles think old ocean plastic smells delicious

Smells like chicken.

Smells tasty—that might be what sea turtles are thinking when they chow down on sea debris like discarded fishing gear, plastic bags, and cigarette filters. Researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that ocean plastics that have been colonized by algae and other microscopic ocean life give off odors similar to those given off by food that sea turtles eat. In response, the animals end up eating a whole lot of it. Their work was published this week in the journal Cell Biology.

Plastic doesn’t typically have a strong odor when we encounter it, often in the form of plastic bags or six-pack plastic rings. But the material becomes home to some odorous sea life once it spends time in the ocean. Algae and microscopic organisms take up residence on it and release smelly volatile compounds such as dimethyl sulfide. These compounds make the material begin to smell like food sea turtles eat.

To better understand the sea creatures’ attraction to this tainted sea plastic, study author Kayla Goforth and her colleagues created their own by submerging empty plastic water bottles in the ocean at the University of Georgia Marina Extension in Savannah for several weeks, replicating what would happen if such a bottle was, for instance, washed off a beach.

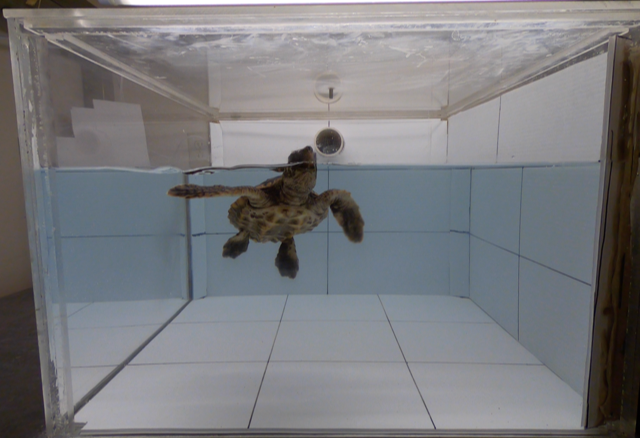

Once the plastic bottles were ready, the researchers recruited a crack team of fifteen captive-reared loggerhead turtles (most of whom were named after characters from “The Office”, Goforth says). They tested the turtles individually in an experimental tank.

“We had a PVC pipe running into a turtle tank and the odors were blown across the surface of the water with a fan,” study author Kayla Goforth says. They tested out four different odors: deionized water and clean plastic as controls, as well as the turtles’ food, and the aged sea plastic.

While the smells were being wafted one by one over the turtle tank, the team monitored how much time the turtles spent with their noses out of the water and how many breaths they took. Loggerhead turtles generally spend 4 to 5 minutes underwater and exchange air quickly when they do surface, so every breath is significant.

They found that the odor of the sea plastic prompted turtles to spend an “indistinguishable” amount of time above water from the time spent sniffing their actual food, the researchers write. That duration was more than three times as long as the turtles spent huffing the deionized water and the clean plastic bottle.

That means turtles in the ocean are probably finding plastic because of the smells it has picked up, Goforth says.

These findings suggest that a primary reason sea turtles end up eating and becoming tangled in plastic is because they smell it out, just like they smell out food. This challenges the standing hypothesis that sea turtles end up eating so much plastic solely because it *looks* like food—an example being floating plastic bags that resemble jellyfish. Goforth and her colleagues aren’t ruling out sight as part of what tempts the turtles, but they think smell is an important component.

“This is a study that needed to be done 20 years ago. I’m glad someone finally did it,” says Jeanette Wyneken, a Florida Atlantic University Marine biologist who also studies sea turtles. Although the results don’t surprise her, she says they do provide a clear mechanism for why sea turtles seek out ocean plastic. Now if we could just stop putting it in the ocean in the first place.