Scientists have new moon rocks for the first time in nearly 50 years

China’s Chang’e 5 mission returned moon rocks that are already helping scientists understand our moon’s history.

The first delivery of lunar rocks and soil since the Cold War is already showing traces of intense surface conditions in the moon’s ancient past.

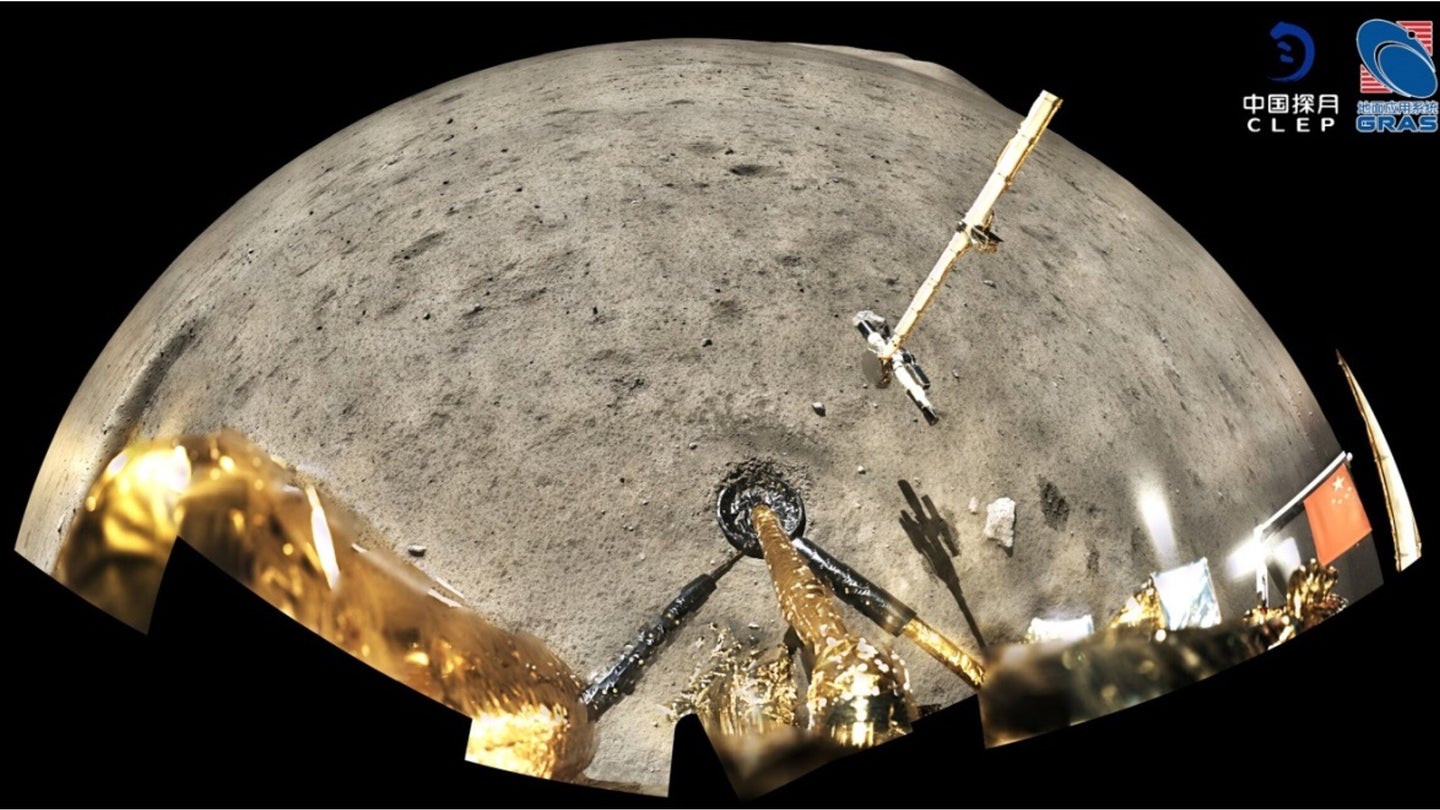

The Chinese National Space Administration’s Chang’e 5 lander touched down on the moon on Dec. 1, 2020. A little more than two weeks later, it brought back samples of lunar rock and regolith which it had drilled and scooped from the landing site in the Oceanus Procellarum region—a massive dark swath a few thousand kilometers wide, visible on the nearside of the moon. Within this lowland area, the landing site is one of the geologically younger regions of the moon, and the samples are the youngest ever to be returned to Earth for analysis.

Apollo 11 returned the first lunar samples to Earth in July 1969. But no mission has brought moon rocks or soil back to Earth labs since the Soviet Union’s Luna 24 mission in 1976, making Chang’e 5’s samples the first in 45 years. The mission is the fifth in the country’s moon exploration history, and is named after a goddess of the moon in Chinese mythology.

“Chang’e 5 mission is a milestone, after [the] Apollo and Luna missions, of human’s exploration of the moon,” says Yuqi Qian, a planetary geology Ph.D. student at the China University of Geosciences who was part of the team that did the preliminary analysis of the samples.

Qian announced the team’s results at the recent Europlanet Science Congress, an international planetary science conference.

[Related: The moon is (slightly) wet, NASA confirms. Now what?]

Scientists’ knowledge of the moon has changed dramatically since the previous sampling missions, Qian says, and this is the first time they’ll be able to compare their knowledge with new samples to see “whether we have a correct understanding of the moon.”

China’s space agency decides which proposed experiments will get to make use of the almost two kilograms of fresh samples. “We are so lucky because the Chang’e 5 sample application is so competitive,” Qian says.

The China University of Geosciences applied for the first batch of returned samples and acquired just 200 milligrams of Chang’e 5 cargo in July. The Chinese National Space Administration received 85 proposals and only 31 of them were approved, Qian says.

Before Chang’e 5 returned the samples, Qian tried in a previous study to judge the age of the landing site, and arrived at an estimate of 1.8 to 2.2 billion years old, based on remote sensing data. When the team obtained the samples, they found that the area was right in the middle of his estimate’s range—about 2 billion years old, Qian says, which was a big relief.

The team found that about 90 percent of the sample were mare basalts—rocks local to the lowland region—with the remaining 10 percent a mix of exotic materials from rarer sources.

These exotic materials included “non-mare materials” like distant impact ejecta, glassy volcanic beads, remains of fallen meteorites, and silica-rich matter from lunar shield volcanoes.

This sample makeup allowed the team to guess at the history of the region using geological forensics. They found that the impact that caused the 39 kilometer wide Harpalus crater probably threw ejecta all the way to the Chang’e-5 landing site 300 kilometers away, which made up a large amount of the exotic material. Two more huge and far off craters, called Copernicus and Aristarchus, 1300 and 600 kilometers away, respectively also added a significant amount of exotic material. Though they are distant from the landing site, all three craters were caused by huge impacts that could have flung material across the moon.

[Related: Enjoy breathing oxygen? Thank the moon.]

The volcanic beads also provide a geological record of an ancient, hot moon which still harbored erupting volcanoes. These little droplets fell and cooled in the surrounding space, then rained down onto the lunar surface. The Apollo missions returned some of these beads and scientists learned in 2008 that samples of them contained ancient moon water from deep underground.

Chang’e-5’s samples were also important for determining the age of lunar features because the current aging model works well for features more than 3 billion years old or less than 1 billion years old, but isn’t as accurate for the period in between, Qian says. With these 2 billion-year-old samples, scientists will be able to better calibrate the dating model for the gap, Qian says.

The international science community’s precious trove of moon rocks will hopefully continue to grow soon, with NASA’s upcoming Artemis missions set to bring back many more lunar samples.