Something To Celebrate: The Ozone Hole Is Really Healing

Only volcanoes are being difficult about the 'hole' thing

It might take almost 30 years, but environmental policies do work.

At least that’s the conclusion that can be drawn from an article published in Science today. Researchers revealed that data showed that the ozone layer over Antarctica shows signs of healing, thanks to the signing of the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

The Montreal Protocol was an international treaty in which countries agreed to reduce the use of ozone-depleting substances like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were found in a wide variety of consumer and industrial products at that time.

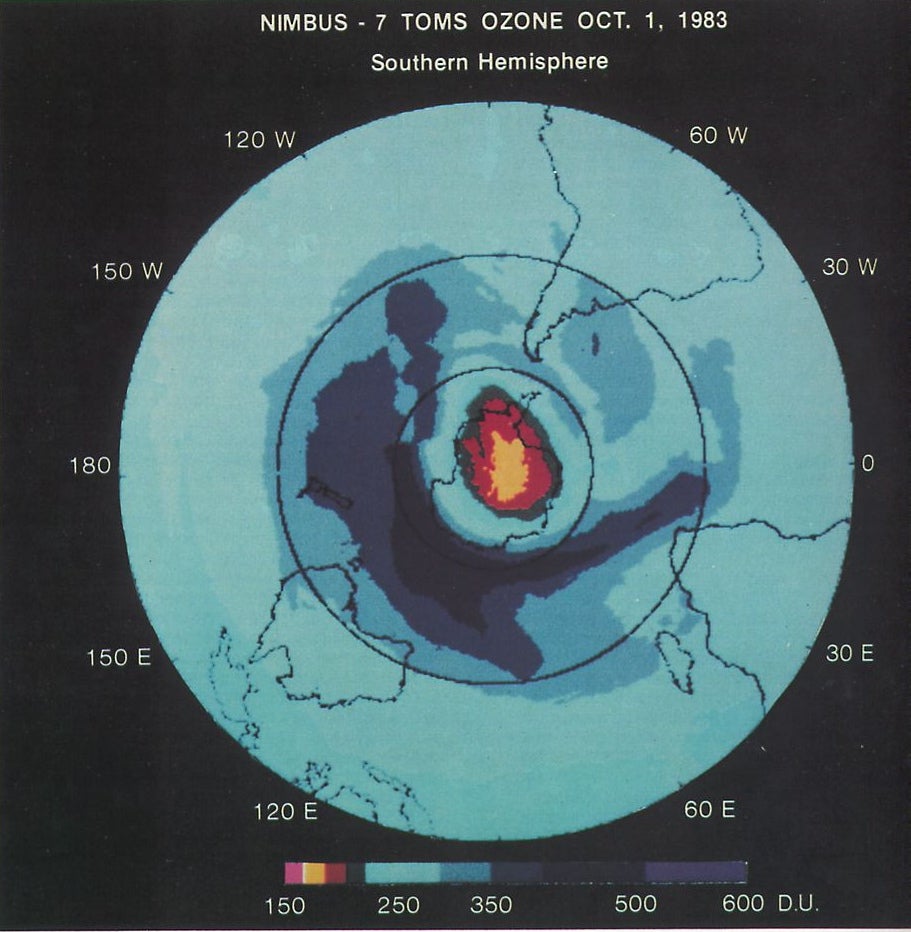

The plan went into effect in 1989, and now, 27 years later, it seems to be working, according to this most recent study and other reports in recent years that showed that the hole was on the mend. The study shows that the ozone hole has shrunk by 1.5 million square miles since its peak in 2000, thanks to a combination of a reduction in CFCs and changing weather patterns.

Ozone high in the atmosphere helps protect life on Earth from harmful radiation. Depletions in the ozone layer are common in the summer months over the Antarctic, leading to the seasonal ‘ozone hole’ that researchers are monitoring. If things continue to go well, the ozone hole could heal completely by the 2050s.

“What’s exciting for me personally is, this brings so much of my own work over 30 years full circle,” lead author of the study Susan Solomon said. Solomon was one of the scientists who called for the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

“Science was helpful in showing the path, diplomats and countries and industry were incredibly able in charting a pathway out of these molecules, and now we’ve actually seen the planet starting to get better. It’s a wonderful thing.”

Back in 1986, Solomon’s work showed that CFCs could break down into chlorine and make their way into clouds in the stratosphere. When the chlorine interacts with sunlight in these clouds, it eats away at the ozone in the atmosphere. Now that there are CFC bans in place, those interactions are happening less often, and the ozone hole should be getting smaller and smaller.

The one hitch: volcanic eruptions. In recent years, volcanic activity has hindered the healing process, with volcanoes sending damaging aerosols high into the atmosphere where they damage the ozone layer. In particular the eruptions of Puyehue-Cordón Caulle in 2011 and Calbuco in 2015 contributed to much larger holes than would normally be expected. In fact, the 2015 hole was the largest on record.

We might not be able to control the actions of volcanoes, but this research is a hopeful sign that humans might be able to correct the errors of our past.

“We can now be confident that the things we’ve done have put the planet on a path to heal,” Solomon said. “Which is pretty good for us, isn’t it? Aren’t we amazing humans, that we did something that created a situation that we decided collectively, as a world, ‘Let’s get rid of these molecules’? We got rid of them, and now we’re seeing the planet respond.”