Smartphone System Rapidly Detects Eye Parasites

Looking for that wormy wiggle

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

In Central Africa, many diseases are caused by parasites that infect people through insect bites or contaminated food or water. Once doctors know that a patient has a particular parasite, many of them are easy to get rid of with antiparasitic drugs. But if a patient is infected with the parasitic eye nematode Loa loa and undergoes antiparasite treatment to get rid of the Onchocerca volvulus worm that causes river blindness, the treatment can cause permanent brain damage or even death.

As a result, public health organizations have stopped doling out antiparasitic medications to large populations and are now waiting to test patients for Loa loa before treating them — putting patients at risk in the interim. Now a team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley have developed a new technique using video and a smartphone to detect the Loa loa parasite in a blood sample, cutting down the time between diagnosis and treatment that could be critical to saving lives. The researchers published the results of their preliminary study, conducted in Cameroon, today in Science Translational Medicine.

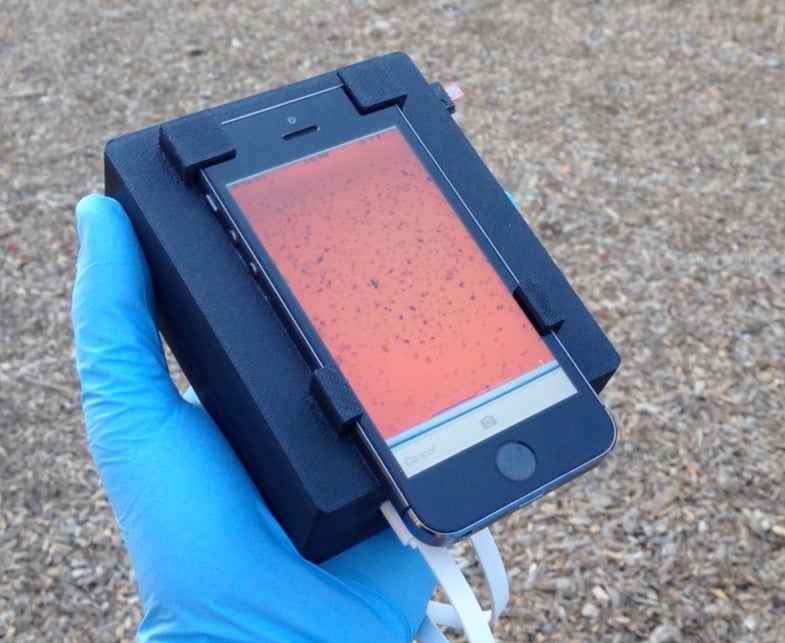

To replace the traditional microscope, the researchers have created a mobile phone microscope, which they call the CellScope Loa. A smartphone is mounted on a 3D-printed base, which contains LED lights, microcontrollers, gears, circuitry, a USB port, and a slot for the blood sample. The researchers also created an app to be used on the smartphone, which connects to the base via Bluetooth. The gears position the blood sample in front of the camera, and software analyzes the resulting video to check for the telltale wiggling of the Loa loa worm. In about two minutes, the screen displays the number of worms it detected in the sample, which helps doctors give patients treatment that won’t endanger their lives.

In this initial test of just 33 patients, the CellScope Loa helped reduce the rate of human error in identifying the Loa loa. The researchers intend to drastically expand their test to over 40,000 patients and, if that goes well, to use this system to help diagnose other parasitic diseases in the future.