Crack, Rats, and T Cells, Oh My!

Rats whose DNA changes with grooming, fetuses less damaged by cocaine than tobacco, and more in this week's round up

Good news, crackheads! You can now smoke, snort, or freebase with impunity while pregnant, and your baby will probably only turn out a little weirder than it would anyway.

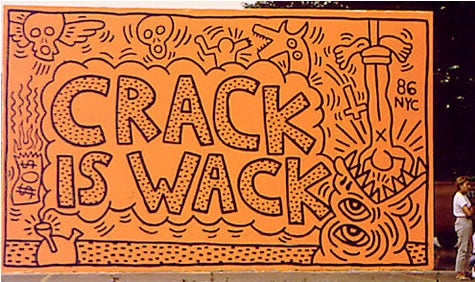

Ok, we’re kidding. But still, widespread panic during the early ’90s that a generation of children would grow up crack-addled was overblown, the New York Times reported last week. The Maternal Lifestyle Study, a longitudinal study of at-risk mothers and their babies that began at the peak of the crack epidemic, has concluded that differences between normal children and ones who were exposed to cocaine in utero are tiny and unpredictable, if they exist at all. “Crack babies” tested at age seven did not have meaningfully lower IQs or language skills than their peers, and cocaine doesn’t even appear to be as bad for a developing fetus as legal drugs like alcohol and tobacco.

Meanwhile, over at the University of Wisconsin, researchers have been spending three hours a day tickling baby rats on the belly. As fun as that sounds, they were actually doing it in the name of science, to prove that a mother’s behavior towards her infant can have a strong effect on the child’s gender expression. Young male rats are usually the object of more maternal grooming and licking, which apparently helps their genitalia develop. But when the Wisconsin scientists applied the same intensive touching regimen to a group of girl-rats, not only did the number of estrogen receptors in the stroked females decrease, but their actual DNA changed–permanently, the researchers suspect. This is a groundbreaking finding–as _The New Scientist_ puts it, it’s “the first time that epigenetic influences outside of the womb have been linked to sex differences in mammals.” In other words, it’s not just the genes and the hormones anymore!

And in other mother-baby-awesomeness news, researchers at UCSF have shed light on one of the tactics that moms use to help their fetuses develop an effective immune system: immigrant cells. Starting in the second trimester, regulatory T cells produced by a pregnant woman drift through the placenta and into the baby, helping its immature immune system learn to tell the difference between healthy tissue and invaders that need to be attacked (the usual suspects: viruses, bacteria, parasites). Grown adults might even still have a few of their mother’s cells buried deep in their lymph nodes. The knowledge that our immune systems have been trained since pre-birth by infusions of “helper” T cells might allow doctors find newer and more effective ways of preventing rejection after an organ transplant.