Future Human: The Evolution of Immediate Emotion

Why a grizzly gets you shivering—but not global warming

In my Science Confirms the Obvious post today, I discussed the first psychological proof (so say the authors) that humans can indeed experience emotions without immediately knowing why. We do this, they say, because we evolved that way. True, scientists love that explanation, but here it’s quite intriguing.

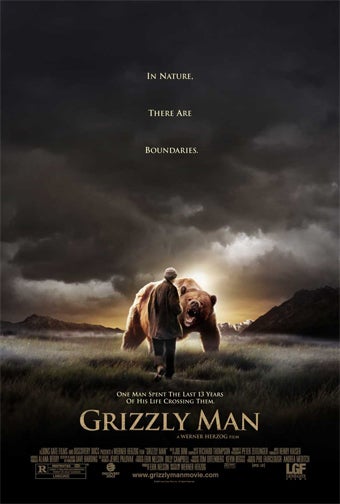

Say you’re walking through the woods and encounter a grizzly bear. You see it and freeze that instant—even before your stomach drops with fear.

“After all, you are likely to live longer if you immediately stop moving at the sight of a growling grizzly bear,” write researchers Kirsten Ruys and Diederik Stapel of The Netherlands’ Tilburg University, “and do not need full awareness for such a response to be instigated.” Given the flood of unexpected stimuli we face moment to moment, quick reactions make sense for survival.

You, that bear, and other animals experience emotions such as fear, anger, or disgust. But only a few species are aware of their emotions. This ability helps humans judge and respond to the behavior of others in order to navigate social situations and, ultimately, grease the wheels of complex society.

The study got me thinking about a talk given by Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert at last October’s Pop!Tech conference. He expounded on why humans are so savvy at grasping immediate threats like grizzly bears or baseballs hurtling at our heads but suck at grasping abstract, slowly approaching ones like global warming. According to Gilbert, a “very large part” of our brains is devoted to dealing with immediate threats, but a “very small part” is concerned about planning for the future.

Humans, apparently, are still in the early stages of evolving extended response mechanisms. But it seems likely that by the time we portion more of our brain to long-term dangers, there will be few grizzly bears around to worry about, and a whole lotta global warming.