Future Human: Were Hobbits Victims of a Brain-Eating Disease?

The debates—and diagnoses—of the tiny Flores fossils rage on.

When there is only one skull to study and at least 65 scientists studying it, you bet there will be squabbling.

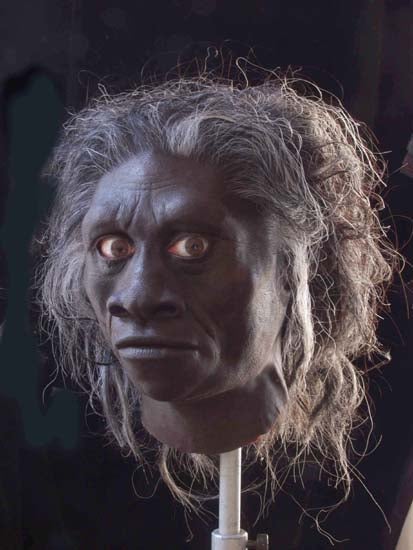

I’ve been following scientific news of the diminutive Flores hominids—the meter-high beings with brains the size of an orange—ever since the astonishing fossils were first discovered on the Indonesian island in 2004. Recently, three new papers have emerged, and now things are really getting weird.

The discoverers and many other scientists think the so-called “hobbit” is its own species, Homo floresiensis. The bones, they say, resemble species much older than our own. Yet the Flores individuals lived as recently as 12,000 years ago, long after Neanderthals had perished in Europe. The find upended our smugness that Homo sapiens species has remained the lone hominid on Earth since then.

Some researchers propose the Flores fossils are Homo sapiens after all—but victims of a disfiguring disease or malnutrition. Microcephaly has been suggested, as has a dwarfing disease called Laron syndrome. Each has or will be debunked by Florida State paleoanthropologist Dean Falk and colleagues.

The affliction-of-the-month—cretinism—is also poised to tumble. The growth of cretins is stunted from a congenital iodine deficiency. But a critical mass of others investigating the Flores fossils, including Stony Brook’s William Jungers, say they lack key features of this disease.

Provocatively, the cretin team also maintains that these beings turn up in Flores folklore as ebu gogo, or “greedy ancestors”:

“Unlike ‘spirits’, ebu gogo are described as mortal, without supernatural powers and no longer present. They lived in caves (lia ula, children’s cave), were short, ‘roughly built’, hairy, ‘pot bellied’, stupid, the females had ‘pendulous breasts’, they stole food, could not cook and had imperfect language (Forth 1988). These characteristics are all consistent with ME cretinism…”

Two more studies (last week in Public Library of Science ONE and today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ) continue the pathology vs new species debate even further.

I asked Jungers his take on the apparent urge to pathologize. “I consider it to be a scientific example of cognitive dissonance,” he said. “Here’s something out of the blue, no one anticipated; everyone’s got their mind made up about the course of [human] evolution. To have your scientific worldview jarred like that is difficult to accommodate. It’s easier to dismiss it than to assimilate it.”

Skepticism, of course, is the muscle of scientific inquiry. But one wonders if the scenario of stunted, hirsute, potbellied misfits banished to a cave is too compelling to ignore, even when the bulk of the emerging evidence suggests that evolution alone—albeit a more complex version than we are now comfortable with—could have produced them. Perhaps Knowing Man’s (AKA Homo sapiens) certainty that it knows itself is simply too hard to relinquish.