Blood Simple

A new machine that makes any blood type universal could lessen the risk of fatal transfusion mix-ups

In 2003 Tawnya Brown was awaiting bowel surgery in a Northern Virginia hospital when she decided to switch beds to be closer to the window. The move ultimately killed her. During surgery, Brown mistakenly received two pints of A-negative blood. She was O-positive. An investigation revealed that a technician had drawn blood from the wrong patient. Within minutes of the procedure, the 31-year-old suffered a fatal hemolytic reaction, which resulted in plunging blood pressure and kidney failure.

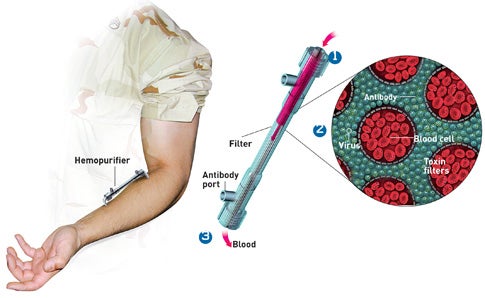

Blood mix-ups, though rare, are still one of the most feared mistakes in transfusion medicine. “It’s the biggest threat today,” says Dr. Kathleen Sazama, a transfusion expert at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Even an ounce of mismatched cells can trigger a potentially lethal immune response, causing blood clots and internal bleeding. But now scientists at a Massachusetts biotech firm may be on the brink of eliminating most transfusion errors and ensuring a steady supply of blood to the nation’s hospitals. Their solution is a device that converts all blood into type O, the most coveted of the four major blood types because it can be safely transfused into nearly any patient. “Press ‘start,’ and the machine does everything else,” says Douglas Clibourn, the CEO of ZymeQuest.

The secret to the device, roughly the size of a dishwasher, is a pair of enzymes newly discovered by Henrik Clausen of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark that can cleave sugar molecules from the surface of the red blood cells. These molecules-called antigens-stud the cell membrane and determine whether someone is type A, B, AB or O. If you receive the wrong blood, antigens in your blood plasma elicit antibodies to attack the foreign antigens.

Clausen, who works as a paid consultant to ZymeQuest, sifted through 2,500 bacteria and fungi before pinpointing a gut bacterium, Bacteroides fragilis, which produces an enzyme capable of pruning the B antigen, and a second bug, Elizabethkingia meningosepticum, which yields enzymes that are effective against the A antigen. Human clinical trials on the A enzyme are already under way in the U.S. and Europe.

The ability to turn much of the nation’s blood supply into type O could be a boon for hospitals, which use it in trauma cases when there’s little time to determine the patient’s true blood type. Routine shortages also can put them in a pinch. ZymeQuest’s machine churns out eight units of type O every 90 minutes. But the technology is far from perfected. Clinical trials must prove that the enzymes leave blood cells unscathed and that they convert all the cells in a unit of blood to type O. If even a few unconverted cells linger, the blood could provoke an immune reaction. “This is the beginning,” says D. Michael Strong, the vice president of the Puget Sound Blood Center in Seattle, one of the country’s largest blood banks. “There’s still a huge amount of work to be done.”