What engineers learned about diving injuries by throwing dummies into a pool

Pointier poses slipped into the water more easily than rounded ones.

The next time you’re about to jump off a diving board to escape the summer heat, consider this: There are denizens of the animal kingdom who can put even the flashiest of Olympic divers to shame. Take, for instance, the gannet. In search of fresh fish to eat, this white seabird can plunge into water at 55 miles per hour. That’s almost double the speed of elite human athletes who leap from 10-meter platforms.

Engineers can now measure for themselves what diving does to the human body, without any actual humans being harmed in the process. They created mannequins, like crash-test dummies, fitted them with force sensors, and dropped them into water. Their results, published in the journal Science Advances on July 27, show just how unnatural it is for a human body to plummet headlong into the drink.

“Humans are not designed to dive into water,” says Sunghwan Jung, a biological engineer at Cornell University, and one of the researchers behind the study.

Jung’s group have spent the past several years studying how various living things crash into water. Initially, they focused on animals: the gannet, for one; the porpoise; and the basilisk lizard, famed for running on water’s surface before gravity forces their feet under.

Those animals’ bodies likely evolved and adapted to their aquatic environments. They might need to dive under the water to find food or to avoid predators swooping down from above. Humans, who evolved in drier, terrestrial environments, have no such biological need. For us, that tendency makes diving much more dangerous.

“Humans are different,” says Jung. “Humans dive into water for fun—and likely get injured frequently.”

[Related: Swimming is the ultimate brain exercise. Here’s why.]

Jung and his colleagues wanted to measure the force the human body experienced when it crashed into the water surface. To do this, they 3D-printed mannequins and fitted them with sensors. The sensors that could record the force the dummy diver was experiencing, and in turn, how that force changed over a splash.

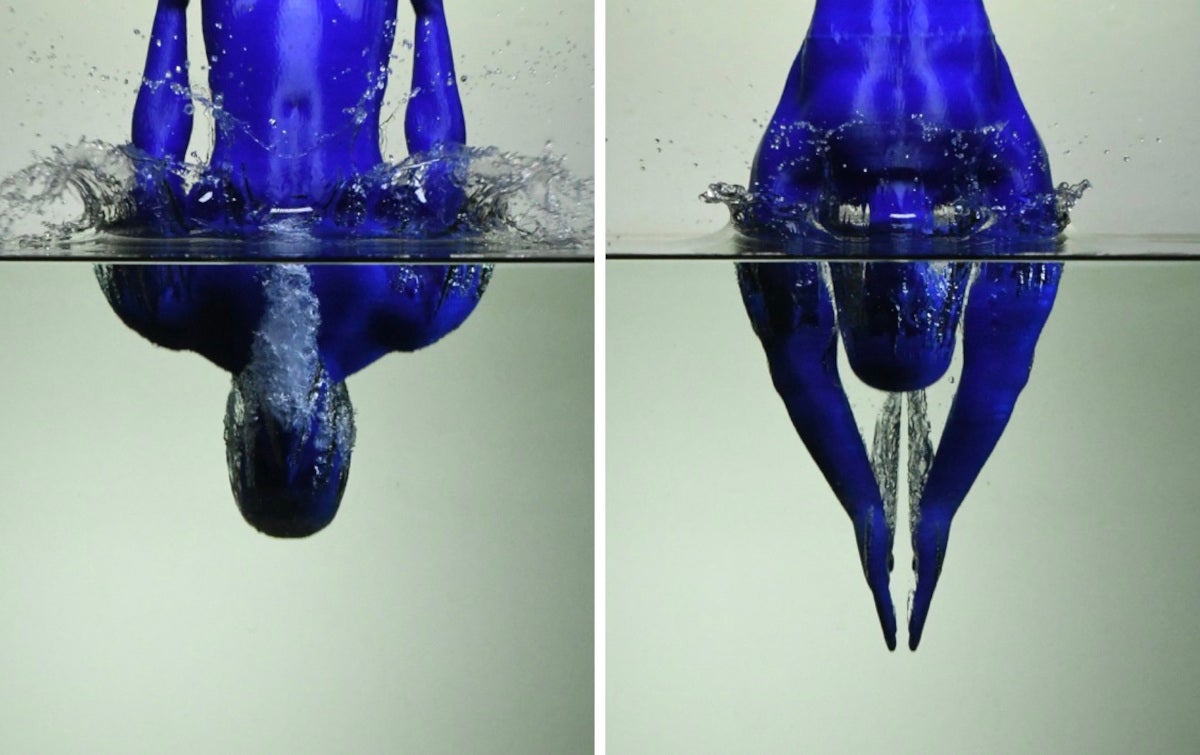

They measured three different poses, each mimicking one of their diving animals. To emulate the rounded head of a porpoise, a mannequin dropped into water head-first. To emulate the pointed beak of a bird, the second pose had the mannequin’s hands joined in a V-shape beyond its head. And to copy how a lizard falls in, a third pose had the mannequin plunge with its feet.

As the bodies experienced the force of the impact, the researchers found that the rate of change in the force varied depending on the shape. A rounded shape, like a human head, underwent a more brutal jolt than a pointier shape.

From this, they estimated a few heights above which diving in a particular posture would be dangerous. Diving feet-first from above around 50 feet would put you at risk of knee injury, they say. Diving hands-first from above roughly 40 feet could put you through enough force to hurt your collarbone. And diving from just 27 feet, head-first, might cause spinal cord injuries, the researchers believe.

You likely won’t encounter diving boards that high at your local pool, but it’s not inconceivable that you’d jump from that high when, say, diving from a cliff.

“The modelling is really solid, and it’s very interesting to look at the different impacts,” said Chet Moritz, who studies how people recover from spinal cord injuries at the University of Washington and wasn’t involved with the paper.

Spinal cord injuries aren’t common, but poolside warnings beg you not to dive into shallow water for very good reason: The trauma can be utterly debilitating. A 2013 study found that most spinal cord injuries were due to falls or vehicle crashes—and diving accounted for 5 percent of them.

But Moritz points out that the spinal cord injuries he is aware of come from striking the bottom of a pool, rather than the surface that these engineers are scrutinizing. “From my experience, I don’t know of anyone who’s had a spinal cord injury from just hitting the water itself,” he says.

Nonetheless, Jung believes that if people can’t stop diving, then his research may at least make the activity safer. “If you really need to dive, then it’s good to follow these kind of suggestions,” he says. That is to say: Try not to hit the water head-first.

Jung’s group aren’t just doing this research to improve diving safety warnings. They’re trying to make a projectile—one with a pointed front, inspired by a bird’s beak—that can better arc through deep water.

Correction (July 28, 2022): Sunghwan Jung’s last name was previously misspelled. It has been corrected.