Now that Food Tech week is winding down here at PopSci, it’s time to sit back, rest our hands on the shelves of our full bellies and listen to the old timers tell us a few yarns about back in their day. We’ve already probed the archives for a few strange culinary suggestions, but there is more yet to come.

Click here to explore the gallery

We’ve collected here a motley assortment of PopSci’s past visions of the future of food, from milestone inventions like dehydration and quick-freezing, to off-the-wall ideas like whale farming, or shining UV light on gas to somehow create vegetable matter.

PopScis of old may not have envisioned a day when you could slice your breakfast pastry with a water jet, but we did think it was a good idea to shoot it full of atomic radiation. So, there’s that.

Urban Farming, April 1920

The concept of urban farming has really taken off of late, with people concerned with freshness and frightened of the growing problem of food deserts–cities that rely on importing food because they have nowhere to grow their own. In 1920, PopSci suggested bringing country chickens to the big city, where they’d be closer to the people who were actually eating them. “The logical place to run a future poultry farm will be in a building in the city in which the product is to be consumed,” our writer said. Of course, his suggestion was also characterized by the cramped conditions of factory farming (“thirty thousand eggs occupying a space scarcely larger than a hall bedroom”), so it’s hardly perfect. But the idea of a “chicken skyscraper” almost sounds like a vertical farm, a concept that still fascinates us today. Read the full story in The Skyscraper Chicken Farm.

Plant Hunters, November 1922

“Plant Hunters” sounds like the name of a boring Travel Channel series (though, if I’m being honest, I might watch that), but in reality, they were researchers like the one you see to your left who scoured the world for cheaper, more wholesome crops to farm in America. Apparently, it was a dangerous job, too, as Dr. Frank N. Meyer, pictured here, “perished while seeking new foods for us in a remote corner of Asia.” Some of the plant hunters’ key finds included Japanese rice, Guatemalan avocadoes and Durum wheat. Scientists in a lab closely examined all “immigrant plants” for potentially harmful insects or diseases before we went about sticking them in our soil. Of course, scientists then, as now, were concerned that all Americans really want to shove down their gullets is crap. Many of the plant hunters’ discoveries went largely unnoticed, said the director of the U.S. Service of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction. “If one per cent of the money spent in advertising chewing gums or breakfast cereals could be applied to advertising the varied vegetable immigrants thus introduced, the American dinner table would boast scores of new, cheaper, and more wholesome foods,” the article reads. Read the full story in How Plant Hunters Risk Lives to Find New Foods for Your Table.

Artificial Photosynthesis, April 1923

In the 1920s, Dr. Herman A. Spoehr was on a mission to discover the secret life of chlorophyll, hoping to unlock the mystery of how plants form sugars from sunlight, water and air. Solving this puzzle was the key to creating massive sugar farms in the desert, like the one pictured here. Glass pipes in mirror-lined troughs would be filled with water charged with carbon dioxide, and set out in the sweltering desert sun, hopefully mimicking the process of photosynthesis without which we would have no food. Nearby factories would take the byproducts of the desert sugar farms and turn them into foodstuffs. Read the full story in Noted Scientists Grapple With Food and Fuel Famine.

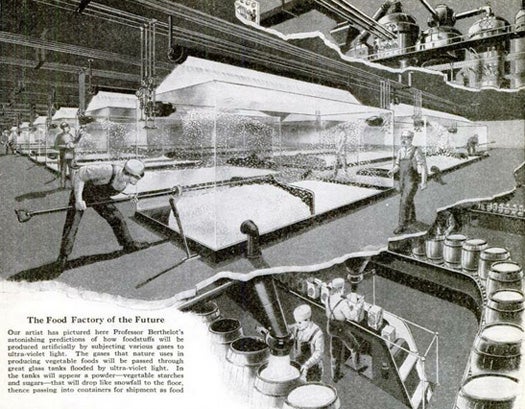

Turning Gases into Vegetables, August 1925

Why bother farming vegetables, hoping that rain and good weather will bring a hearty crop, when you can just blast some gas with UV light and have vegetable matter fall to the ground like snow? This was the brainchild of French scientist Daniel Berthelot. (We spent a good amount of this article extolling Berthelot’s credentials, perhaps to make his idea sound more plausible?) Berthelot subjected naturally occurring gases to ultraviolet light, which produced sugars. He envisioned taking this process and manufacturing it on a large scale: factories full of glass tanks covered by UV lamps. Gases would enter the tanks through pipes, and vegetable material would rain down into fluffy piles which workers could then harvest. While wearing protective goggles, of course. Read the full story in Factory-Made “Vegetables” our Future Food?

The Big Freeze, December 1937

A quick-freezing process invented in the 1930s claimed to take 40 minutes to preserve food, which could then be stored for two years and would “taste as they would have when picked.” (Though, unless technology has regressed from then to now, I suspect there was still a hint of freezer burn.) Fruits and vegetables were bleached in boiling water to help retain their color. Many foods, including meats, were first soaked in a near-zero brine solution to lock in flavor. After being subjected to the necessary preparations, food was frozen in chambers full of methylene gas which reduced the temperature by 80 degrees in 40 minutes. Read the full story in New Freezing Process Keeps Food Fresh for Two Years

Dehydration, January 1942

It has long been a dream of mine to dehydrate an entire watermelon down into a single chip, both to see how big the chip would be and because I suspect it would be packed with flavor. This dream could never be realized without the “magic quick drying processes that drive out bulky moisture while leaving in the flavor and vitamins.” And it still probably won’t be. But thank god they got rid of that bulky moisture, otherwise we wouldn’t have such kitchen staples as concentrated juice, those banana flakes that come in cereal, powder that turns into cranberry jelly or clam “pennies” that dissolve in water to form clam broth. These products, this article says, were the closest we had yet come to the tablet meals of the future that everyone’s always raving about. Methods varied, for example, you see to your left one that involves tunnels full of drying compartments, and another that atomizes milk out of a nozzle to form powdered milk. Read the full story in Now It’s Quick-Dried Foods.

Abundant Algae, July 1950

In 1950, the Stanford Research Institute put together a “pre-pilot plant” to demonstrate the efficiency of mass-producing the algae plant Chlorella, which harvests the sun’s energy “far more efficiently than any present farm crop,” thereby greatly increasing yields per acre. And without any stalks or other unsavory bits to remove before eating, “the resulting mass is entirely edible.” Hey, if it works for fish, it should work for us. Read the full story in Harvested Sunlight Grows by the Tankful.

Fighting Decay With Radiation, April 1956

This gives a whole new meaning to “zapping some dinner.” The Department of Defense pledged $10 million to support research on shooting things that we put in our mouths with atomic radiation. As you can see from the picture, the rays help prevent mold from growing on waffles, macaroni and cheese, bread, potatoes and unidentifiable lumps of beige food product. And, if you’re lucky, after eating them, you may be eligible to star in The Avengers 2. Read the full story in Atomic Rays Keep Food Fresh.

Moby Beef, November 1960

“Whales are cattle,” asserts this 1960 story about how to feed a hungry world. And their meat tastes remarkably like beef, apparently. Whale meat was considered a delicacy in Japan, and a single whale was worth $30,000 dollars in meat and other products that could be made from it. PopSci wasn’t advocating a mad rush of Ahab-like quests to kill wild whales and harvest their flesh, though. We instead imagined a world where we farmed the sea like the land, protecting and breeding whales like giant ocean cattle. Read the full story in Will a Hungry World Raise Whales For Food?