Oil From The Deepwater Horizon Spill Sickened Fish For At Least A Year

A new study discovered illness and birth defects among Gulf Coast fish nearly 16 months after the BP explosion.

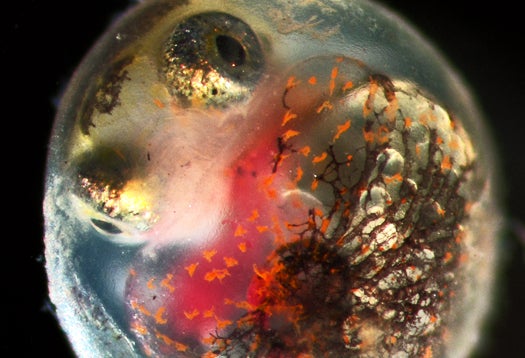

More than a year after the Deepwater Horizon disaster, crude oil continued to sicken Gulf Coast fish, according to a new study. Gulf killifish, which are considered sentinel species that can indicate broader environmental problems, suffered heart defects, delayed hatching and other problems.

Lead author Benjamin Dubansky of Louisiana State University and his colleagues sailed into the Gulf of Mexico four times between May 2010, just after the spill, and August 2011, collecting fish samples. Killifish are abundant and don’t migrate, so they are good subjects for studying the oil’s impact. The expeditions’ time frame coincided with two peak spawning periods for the killifish, according to Dubansky’s paper. The scientists took samples from several un-oiled sites and a sixth site at Grand Terre Island, La., which was directly impacted by oil.

The team monitored the fish to measure how the oil affected them, and they also took some oil from this area back to the lab, where they exposed killifish embryos to it to see what would happen. They found evidence that the fishes’ livers and gills were affected, which indicates damage as the fish tried to breathe in the contaminated water and as their livers tried to metabolize the oil. Fewer fish hatched than would be expected, and among fish that did hatch, the creatures were smaller and experienced swelling around their hearts and in their yolk sacs.

“These data include results that encompass two breeding seasons, and indicate that contaminating oil from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill impacts organismal fitness, which may translate into longer-term effects at the population level for Gulf killifish and other biota that live or spawn in similar habitats,” the authors write.

But co-author Andrew Whitehead, an assistant professor of environmental toxicology at University of California-Davis, notes that not all killifish habitats were affected. Oil showed up in patches rather than coating the entire Gulf Coast, so some fish probably came away unscathed. He added that some of the healthier killifish could serve as a buffer for the species as a whole.

The paper was posted online before publication in Environmental Science and Technology.

[via Futurity]