What’s Behind The NFL Suicides?

An up-close look at chronic traumatic encephalopathy

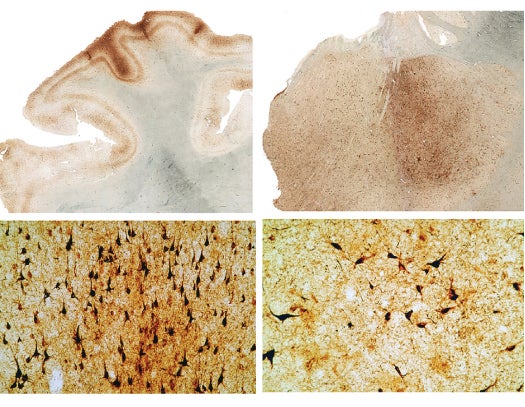

THE DISEASE

For decades, the term “punch-drunk” has been used to describe boxers left permanently loopy after a career of fighting. The clinical name for the condition is chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and it can happen to any athlete who suffers frequent blows to the head. CTE has no known treatment, and doctors can only diagnose it postmortem, by physically examining the brain for symptoms.

WHAT CAUSES IT?

At its most basic, CTE is a cumulative effect from repetitive head trauma—not just concussive blows but also weaker ones. Impacts damage the brain’s neural pathways, and as a result a protein called tau builds up. The more tau along the pathways, the less easily brain signals can move around, which can lead to memory loss, lack of impulse control, aggression, and depression.

HOW COMMON IS IT?

Scientists at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University examine the brains of dead contact-sports athletes. In its first year of operation, 17 of the 18 brains researchers tested had CTE. Also, a team of scientists recently reported that former NFL players are three times more likely than the general population to die from brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR HELMETS?

Because football helmet safety standards were designed to prevent skull fracture, padding has to be stiff enough to weather an extremely hard hit. But stiff cushioning allows a lot of force to reach the head. Over time, that can lead to CTE. Certain companies, such as Xenith, have begun to use adaptive cushioning. It stays stiff during a big impact, but softens during a smaller one.

This article appeared in the January 2013 issue of Popular Science. Read the companion feature “The Helmet Wars” here.